While ruminating on the most curious aspect of ARTBO—namely that it is a public-private partnership run by the city’s Chamber of Commerce with “allies” such as Uber—I considered the reasons why the organizers of my trip were taking an international band of curators, collectors, and critics not only to visit the fair, but also on a bus tour to appraise two other public-private cultural “success stories”—a new museum building and a series of urban renewal projects, both in Medellín. As such, this very model—the pooling together of public and private monies as a strategy to advance art and culture in Colombia as a marketable resource—could be the subject of this review. We might, moreover, consider how these instruments are being marketed to counter the country’s stigmatization as a narco-capital.

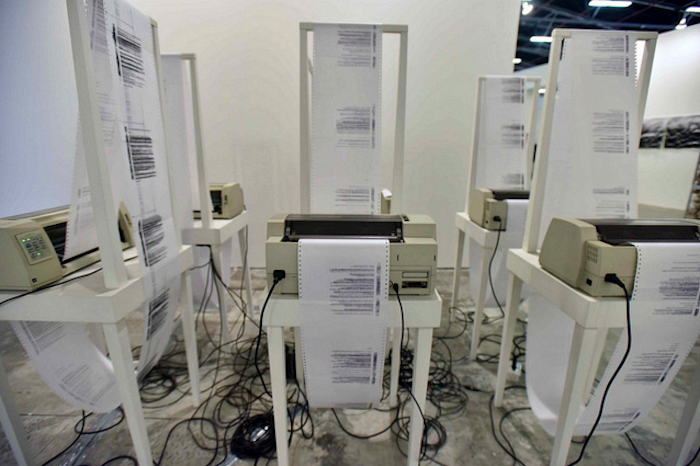

Now in its 11th year, ARTBO offers more of what you might expect: a main section offering the obligatory blend of local and international galleries, a few bijoux curated and themed sections, a talks program, and all the other trimmings of a well-heeled yet staid affair. To its credit though, the fair also presents ARTECÁMARA, a section dedicated to local artists without commercial representation, selected through an open call process. Given that business councils exist to promote local enterprise, this initiative hardly seems out of place within the art fair’s commercial model. That said, if ARTECÁMARA is to be viewed as an artistic bellwether in its own right, then the country’s drawing and landscape traditions—ensconced since at least the time of the Escuela de La Sabana in the late nineteenth century—is still strong, as demonstrated in works by Rafael Andrés Díaz Vargas, Juan Cortés, Laura Ceballos, and others, while the post-internet wave is starting to crash and be surfed by artists such as Geraldiny Guerrero Muñoz, Sofía Reyes & José Aramburo, and Francisco Alejandro Cifuentes.

With imports in mind, though, the balance between national and multinational commerce is far more skewed in the main section of the fair: of 68 galleries, 53 are based abroad. Outside of casual networking, just how this foreign-friendly setup benefits anyone beyond local collectors linked to extra-national dealers is hard to parse. ARTECÁMARA artists may get a deal, a dealer, or some other form of baptism into the market—but whether resources could be better spent by supporting museums, such as the underfunded MAMBO (Bogotá’s Museum of Modern Art), is another question altogether. When queried on how the chamber measures—and justifies—the use of public money for this, fair director María Paz Gaviria Múñoz brushed off a fellow journalist by saying that they “don’t look at numbers” and would not qualify the expenditure. Instead Gaviria—who comes from a powerful political family—repeated platitudes about the positioning of the fair and its growth (explicated through the given metric of gallery and visitor counts) like a mantra. Jostling through the fair’s other materials, which also include an online commercial “teaser,” it would seem that the end game here is to establish Colombia as a node on the multinational art circuit. The message that this is Latin America’s “primer” fair was pushed over and over—Miami Basel beware! Context is everything though, and it should be noted that Colombia’s history as a war-torn and crime-ridden country over the last several decades has not only scared away tourists and their dollars, but most foreign investment as well.

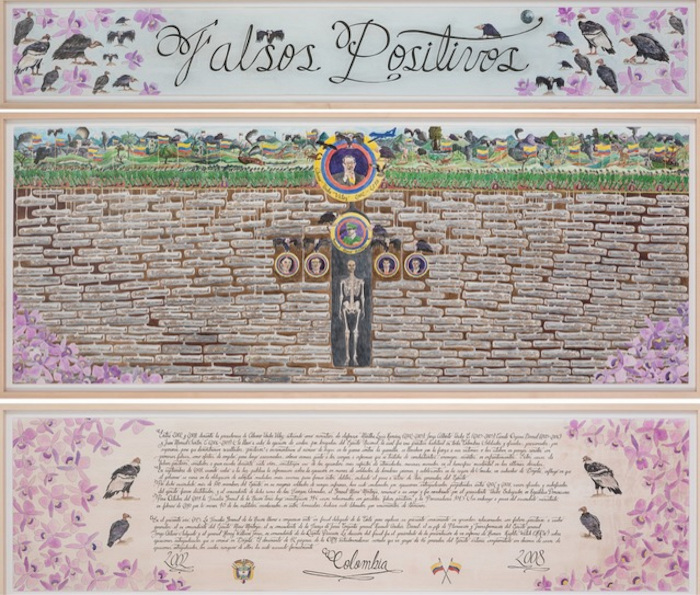

In a 2010 McKinsey report on Colombia’s economic development, former Minister of Commerce, Industry, and Tourism Luis Guillermo Plata noted that when the Colombian economy teetered on the brink of collapse around the turn of the millennium, “there was no tourism, no investment—not local or foreign. People were afraid to go out to spend. So as we recovered security, of course, this became the basis for the recovery of the economy and the turnaround of the country.”1 This link between commerce and security might seem logical enough in theory; however, this is to ignore the ministry’s Productive Transformation Program, a series of sweeping reforms launched in 2007 that reorganized Colombian industry around public-private partnerships spanning various sections of the economy. Partnered with a Colombia-USA Free Trade Agreement, the scheme followed various scandals linking US-based multinationals such as banana distributor Chiquita Brands International to extrajudicial killings.2 The following year brought news of the “false positives” scandal3 by which impoverished men were tricked into travelling to remote sites, where they were summarily murdered by the military and dressed as leftist rebels. The practice was used to juke war stats under the watch of then Minister of National Defense Juan Manuel Santos during the Uribe administration—a subject tackled by Colombian artists including Nicolás Paris, Doris Salcedo, and in the main section of the fair, by Jorge Julián Aristizábal. Although these events are now being played out in court, The National Labor School (ENS), a Colombian NGO, has opened several dozen newer cases concerning the murder of trade unionists.4

Returning to the “go shopping or the terrorists will win” model, this September saw Colombia host the United Nation’s World Tourism Organization General Assembly, at which Santos—now the country’s president—spoke of the need to continue the rebranding of the country so as to stoke the guest and services industries and related investment opportunities.5 By extension, the country not only needs to rebrand itself as a safer place, but also as a hip, fun, tourist-friendly destination that has transformed Medellín into “one of the most progressive cities in Latin America,” according to a recent feature in the New York Times’s travel section.6 On a symbolic level, these efforts at renewal have increased civic pride; yet while some have improved residents’ quality of life, recent studies on their impacts in Medellín have not found credible evidence that they necessarily provide financial enrichment for the lesser privileged, nor has a direct link to crime reduction been established.7 The question remains of just how art, design, and the culture industry—and flash urban renewal projects—translate into sustainable gains for all.

colombias_lesson_in_economic_development.

Luis Andrade and Andres Cadena, “Colombia’s lesson in economic development,” McKinsey Quarterly (July 2010), http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/economic_studies/

Michael Evans, “‘Para-politics’ Goes Bananas,” The Nation (April 16, 2007), http://www.thenation.com/article/para-politics-goes-bananas/

Chris Kraul, “In Colombia, 6 sentenced in ‘false positives’ death scheme,” Los Angeles Times (June 14, 2012), http://articles.latimes.com/2012/jun/14/world/la-fg-colombia-false-positives-20120614.

Mike Hall, “Despite Labor Action Plan, Colombian Unionists Still Targeted for Death,” AFL-CIO (July 4, 2015), http://www.aflcio.org/Blog/Global-Action/Despite-Labor-Action-Plan-Colombian-Unionists-Still-Targeted-for-Death.

Walt Donner, “Santos hopes peace in Colombia will boost tourism,” Columbia Reports (September 15, 2015), http://colombiareports.com/santos-hopes-peace-will-boost-tourism/.

Nell McShane Wulfhart, “36 Hours in Medellín, Colombia,” International New York Times (May 13, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/17/travel/things-to-do-in-36-hours-in-medellin.html?_r=0.

Letty Reimerink, “Medellín made urban escalators famous, but have they had any impact?,” Citiscope (July 24, 2014), http://citiscope.org/story/2014/medellin-made-urban-escalators-famous-have-they-had-any-impact#sthash.pVWvCXCY.dpuf”.