In a city where most galleries are located in apartments, the experience of visiting exhibitions goes against the art-tourist impulse to catch as catch can. Stand outside buildings, buzz in, climb stairs, see the neighbors in the hallway—it’s an experience of proximity that is different from viewing art at a fair or a biennial, or even a Chelsea gallery (where the inverse happens, and the glass buildings lining the streets post signs at the entrance to their lobbies reading “this is not an art gallery”), and it allows for an appreciation of the gallery show, that basic structure of presentation that viewers often neglect in the midst of other international festivals.

At times, the domesticity of the galleries inspires nontraditional presentations. At Asymetria there is an unilluminating group exhibition—black-and-white images of urban landscapes and portraits framed and hung horizontally, to echo a filmreel—about the influence of neorealist cinema on Polish photography in the 1950s and ’60s, featuring the works of Zdzisław Beksiński, Jerzy Lewczyński, and Marek Piasecki. But upstairs a project by a younger photographer, Błażej Pindor, is presented as though within a bedroom: there’s a single metal bed in the corner, a couple of clothes hangers on hooks. In the open drawers of a dresser and scattered on a table are photographs from the series “Deconstruction” (2016), documenting the disassembly of Lewczyński’s studio after his death in 2014. Pindor printed these on the photo paper found in Lewczyński’s things, allowing the different qualities of the paper, at times fading and gray, to transform the images’ character. The installation is not the artist’s—it’s the gallerist’s design, meant to invoke the feel of the artist’s studio. Were the furniture Lewczyński’s or the exhibition design Pindor’s no one would bat an eyelid; strange as it is, it’s still also somehow fitting—of the space represented in the photos and the space it’s presented in.

At the Archeology of Photography Foundation—a nonprofit dedicated to the conservation, archiving, and promotion of Polish photographers’ works—the exhibition “Lux” is dedicated to light. As at Asymetria, where a conventional topic led to discovery, in this exhibition Karolina Breguła’s video Photophobia (2016) shifts a commonplace subject into a space for reflection on its absence. Depicting a woman who is afraid of light, the video is shot in largely dark environments, from the office of her bureaucratic job to her way home, on which she takes the bulbs out of streetlights. Indoors, she wraps the bulbs in newspaper and breaks them with a hammer, one by one. Photophobia’s narrative is bleak but its cinematic language is rich, creating haunting images of the protagonist in the dim environments she creates herself.

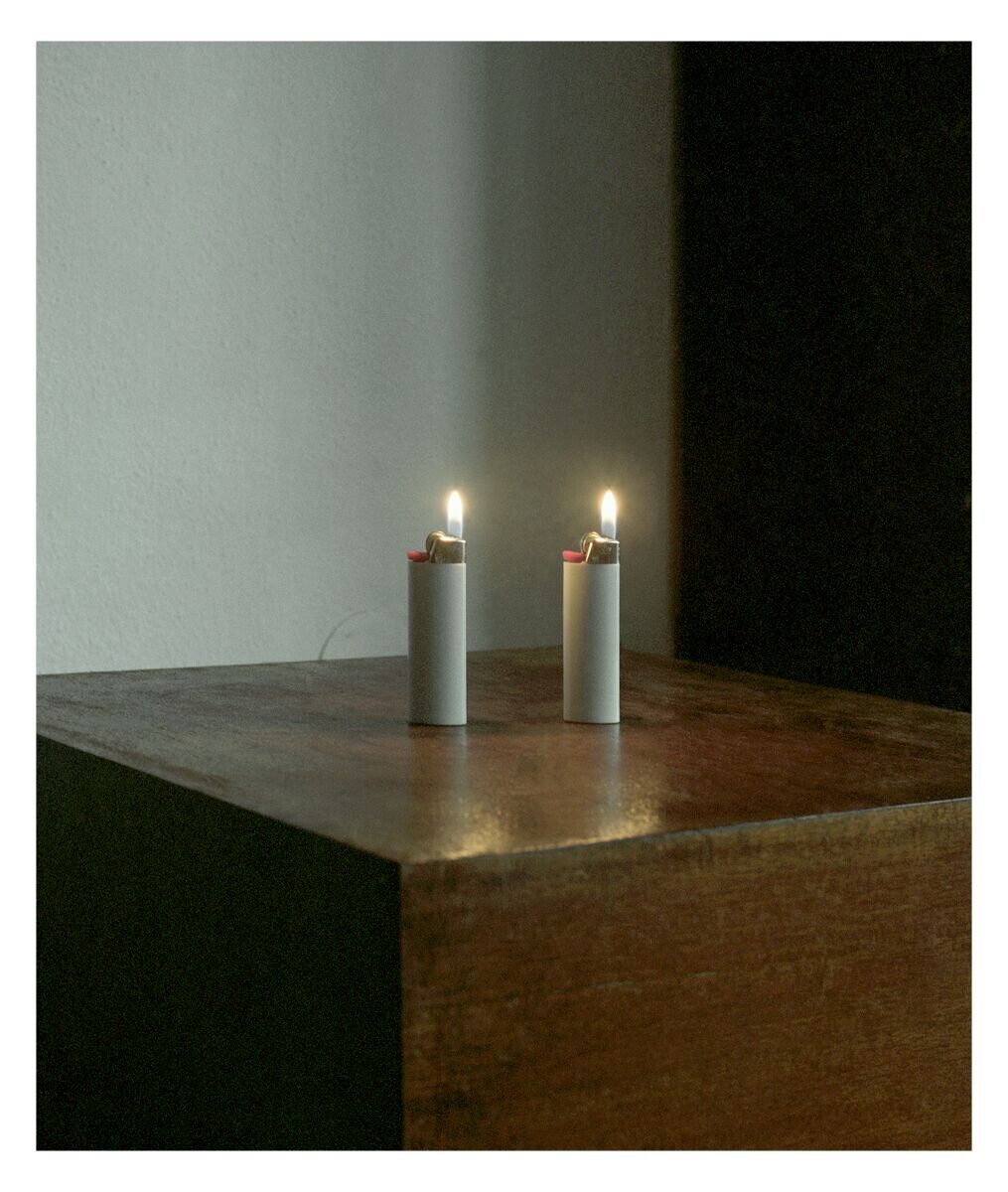

Nearby, Starter, a gallery that has developed its own tradition of presenting three exhibitions during gallery weekend, with one in their space and two in other venues, is presenting photographer Michał Grochowiak. Titled “The Petit Bourgeois,” his solo show is a collection of small, mundane photographs of everyday life: the flames of two identical lighters side by side (Feuerzeuge, 2016), a series of Polaroids of one building (Block of flats, 2015). Photography in Grochowiak’s work lends itself well to this project—a documentation of the minute, which the artist claims is the visual manifestation of daily bourgeois habits. This reference to money resounds in the exhibition “Money to Burn” at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art. The title of the show is ironic in a place where “poverty is the new wealth,” as the exhibition wall text claims. And yet, while the labels are printed on gold paper, foreign currency is still the most common imagery, with a performance by Tomasz Mróz that includes forging $100 bills (Untitled, 2016), a framed $1 bill by Piotr Uklański (it’s the artist’s private souvenir—the first dollar he earned in 1990 when he moved to New York), and a painting by Zbigniew Rogalski of two people sitting on a rug, painting €100 bills in watercolors (Euro, 2003).

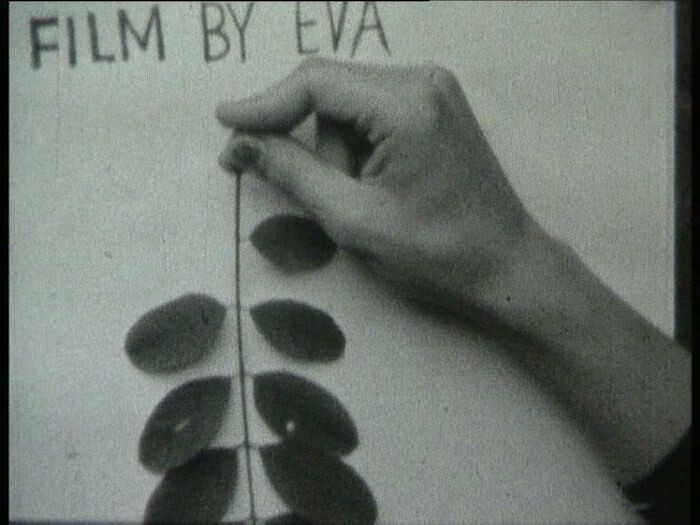

“Money to Burn” has great moments—Maria Toboła’s Amber Kebab (2016) installation of the greasy street food rendered (using resin and LED lights) precious and Azorro Group’s simple and brilliant Proposal (2002), in which the four artists are listening to a voice message left on their answering machine by a museum asking them to participate in a show and laughing out loud when, after explaining the museum will not cover artist fees, travel or production expenses, the exhibition will be “very prestigious.” Much lower in production costs, and yet much more impressive, is a show at Arton Foundation of video works by seven female artists titled “If You Don’t Know Me By Now, You Will Never Never Never Know Me.” With the 1972 song by Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes playing in the background, this small exhibition brought together works from between 1973 and 1982 by Sanja Iveković, Natalia LL, Jolanta Marcolla, Letítia Parente, Ewa Partum, Martha Rosler, and Lisa Steele. Subjects vary from the status of the female body to the changing role of women in society, and seeing Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975) alongside the performative work of Natalia LL is a strong proof that political struggles cross boundaries and borders; the fact that this specific struggle still rings true today is the reason why this small exhibition, with seven videos projected side by side, feels like the most urgent and impressive of all gallery weekend events.

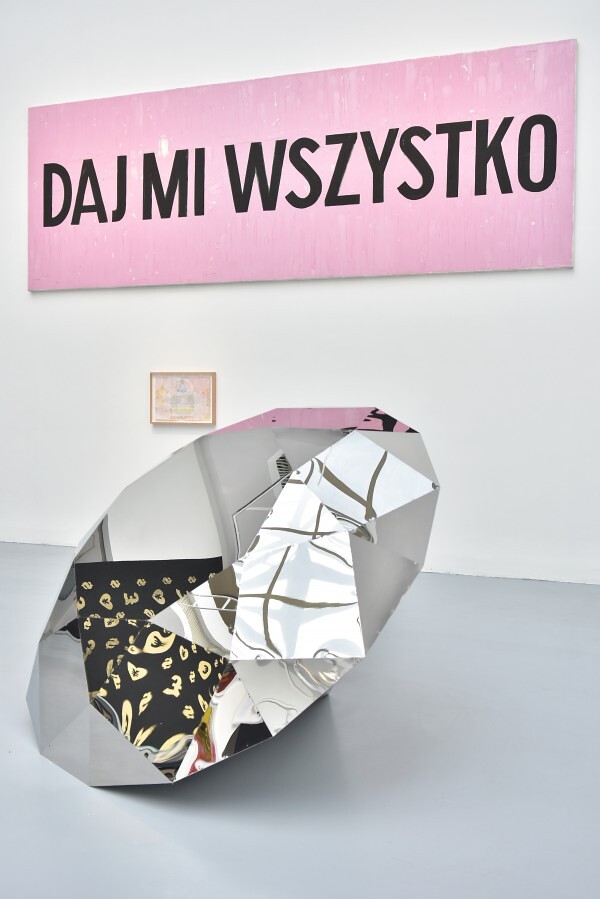

Elsewhere Piktogram, a gallery that grew out of a magazine of the same name (they published sixteen issues before deciding to focus on the gallery) organized an art fair during gallery weekend. Not Fair was housed at the Palace of Culture and Sciences, a grand 1955 building in the Muscovite style. The fair included fourteen galleries, each bringing one installation. Not Fair was supposed to look more like a group show than a fair, and though there weren’t any substantial connections made between the works, there were strong pieces by Zuzanna Czebatul (who Piktogram was also showing at their city center location), Anouk Kruithof (brought by Rotterdam’s Cinnnamon), Eva Grubinger (with Galerie Tobias Naehring, Leipzig), and Damir Očko (from the local Kasia Michalski Gallery).

Though Not Fair highlighted single projects, it still felt like a sideshow to the gallery exhibitions. Gallery weekends are becoming as common as art fairs, which is something to be glad for. Why should galleries spend the equivalent of their yearly rent on an art fair booth when they lease beautiful spaces where they are committed to giving their artists room to explore and experiment? Galleries play a public role as well as a market one, and in the interest of a healthy art scene we need to go see gallery shows, climb the stairs, support the long-term engagement of artists and galleries and the way it manifests in a space.

One of the most famous artworks in Warsaw is also an apartment: Edward Krasiński’s residence and studio on the top floor of a Soviet apartment bloc on Solidarity Avenue in the center of the city is open for viewers by appointment, but was closed during gallery weekend because the building’s staircase is undergoing renovations. Preserved since Krasiński’s death in 2004 by the Foksal Gallery Foundation, the studio remains as the artist had it, including his arrangement of works throughout the space and a unique installation: a line made of blue scotch tape traversing the whole space at the height of 130 centimeters. “I don’t know whether this is art,” Krasiński said, “but it’s certainly scotch blue, width 19 mm, length unknown.”

Over the weekend, outside one of the temporary locations occupied by Starter, I saw a group of young people stretching red tape alongside the interior courtyard of the building. Maybe it was a direct quote of Krasiński, and maybe it was unrelated to gallery weekend. In Warsaw, it’s hard not to read everything in the context of the work done in the city between the late 1960s and early ’80s, in places like Foksal and by artists like Krasiński and Natalia LL. This sense of continuity by reference to a great generation solidifies the impression that the art being shown in Warsaw is local and in direct dialogue with its own history. It’s proof that there’s room for a national context; it’s also evidence that it can be relevant to any viewer. Whether or not it was art, the act was a reminder of how good it is to be outside the tent or the convention center, in a city, paying attention to the specific character of a place.