October 27, 2016–February 26, 2017

Under the artistic direction of Susie Lingham, Director of the Singapore Art Museum, and nine other curators, the fifth edition of the Singapore Biennale, “An Atlas of Mirrors,” showcases sixty artists and three artist collectives from nineteen countries and territories around South, East, and Southeast Asia.

Spanning eight venues in close proximity to one another within Singapore’s art district and old Jewish quarter, the exhibition, with its clear signage and omnipresent air conditioning, provides a respite from the otherwise natural, sweltering, and mosquito-bite-inducing equatorial humidity. Despite this, a certain discomfort pervades the exhibition space. With its title and nine subthemes, the biennale would be confounding to any viewer, even without the mediation necessary for presenting contemporary art to a lay audience. Dominating wall captions fail to elucidate any ideological or social impulses behind the artworks presented, pointing to the exhibition’s slow passivity and abject apolitical nature. While some in the field have criticized previous iterations of the Singapore Biennale for being safe and leaving little room for critique,1 this edition’s passivity poses the question of how one deals with a decade-old biennial born of a capitalist development agenda. The Singapore government originally launched the biennale as the anchor cultural event of the 2006 IMF/World Bank meeting in Singapore in order to highlight the country’s prominence as an international art center.2 The question is especially relevant given that the biennale has repeatedly proven to be a Debordian spectacle—one driven by the promotional language of economic developments and nation-building rhethorics. Since the last iteration, it’s paradoxically become a gesture of Singapore’s greater geopolitical assertions over Southeast Asia.3

If anything, I would have hoped that “An Atlas of Mirrors” would offer a greater opportunity to engage in meaningful discussions already taking place in the region rather than an all-encompassing universalism. Conspicuously absent is any debate that might complicate the supposed neutrality of the acts of mapping and mirroring in light of the different modes of coloniality, post-coloniality, and decolonization present in the region.

The leeway afforded by this blanket invitation manifests across the biennale through a homogeneity of visual textures in the exhibited works and the literal interpretation of its title. Works such as Harumi Yukutake’s Paracosmos (2016), an elegiac, site-specific installation of hand-cut mirrors presented around the central stairway of the Singapore Art Museum; Map Office’s Desert Islands (2009, 2016), an installation of 100 mirrors engraved with individual coordinates of islands, questioning the peripheries of geographical consciousness; and Melati Suryodarmo’s Behind the Light (2016), a durational performance and installation looking at the means of perception through Asian theatrical traditions with the use of a two-way mirror that fades away, at certain points, to reveal a room occupied by a performer, all located within the Singapore Art Museum’s main building, unfortunately can be reduced upon one’s first impression to the common and literal use of materials such as mirrors.

Under the weight of the hyperexpansive theme, some of the biennale’s new commissions are seemingly uneven and tired in presentation and research. Ade Darmawan’s Singapore Human Resources Institute (2016), a cheeky look at the “peripheral histories of capitalism” consists of an installation made of found objects, furniture from offices and domestic environments in Singapore and Indonesia, and literature about the statistics of social demographics and productivity. It seems reminiscent in methodology of Singapore Fiction, a site-specific installation at the 2011 edition of the Singapore Biennale by artist group ruangrupa, of which Darmawan is a member. Furthermore, Darmawan’s work stops short of elucidating the language of capitalism in a context where such ideology is taken as a given. Ahmad Fuad Osman’s Enrique de Malacca Memorial Project (2016), a faux museological and archival installation of a purported Austronesian companion of Ferdinand Magellan, the first person to successfully circumnavigate the globe, takes on the familiar trope of questioning the dominant narrative of the Mat Salleh (white) hero.

Given the statements that the biennale strives to make, it is the works that are grounded in negotiating and problematizing modes of representation within a certain locale that linger in the mind. Witness to Paradise (2016), a curatorial project consisting of works by Nilima Sheikh, Praneet Soi, Abeer Gupta, and Sanjay Kak, looks at Kashmir, its history, and its ongoing conflict in a solid, elegant, and quiet installation at 8Q, an outpost of the Singapore Art Museum. The viewer is greeted on one side with wool, silk, and cotton embroidered garments as part of Abeer Gupta’s The Pheran (2016); four tempera paintings that refer to the nature of destroyed beauty by Nilima Sheik (Another Chronicle of Loss, 2009; Sarhad 3, 2014; Shadows, Stains, 2009; and Testimony, 2008); and Praneet Soi’s Srinagar II (2016), consisting of 24 papier-mâché tiles that take on the language of material culture to explore the plurality of cultural influences in the region. On the other side of the gallery space there is “Witness to Paradise” (2016), a series of 30 photographs by Meraj ud-Din, Javeed Shah, Altaf Qadri, Showkat Nanda, and Syed Shahriyar Hussainya, selected by Sanjay Kak, which depict the past and present violence of the conflict in Kashmir and which disrupt the melancholic landscape established by the other works.

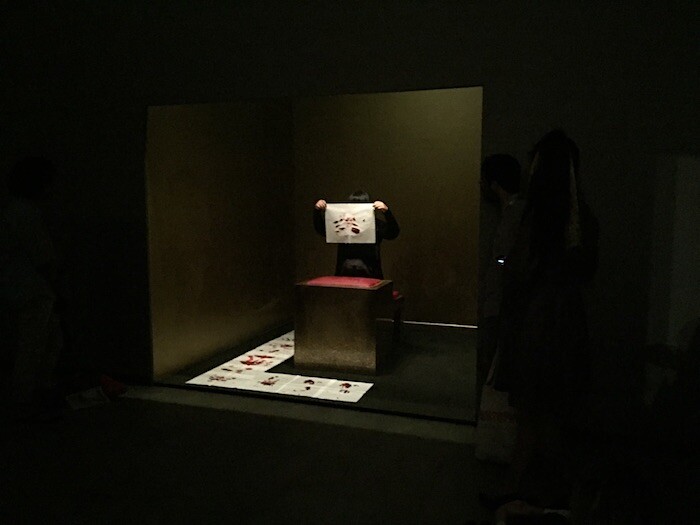

In the same building, Jack Tan’s Hearings (2016) explores how memories are constructed and interpreted. Here, the artist records the experiences of litigants at the State and Family Courts of Singapore in graphic scores, which are then interpreted and performed by a local choir. It risks being overlooked, given the small nook it occupies behind Soap Blocked (2016), an installation by Htein Lin, but the intimacy of the simple setup of dimmed lighting, music stands, and scores functions as a respite from the visual and offers visitors a contemplative moment to consider how the auditory sense takes hold.

Around Singapore, outside the biennale, the aspirations of “An Atlas of Mirrors” are given more rigorous treatment at two different exhibitions: “Incomplete Urbanism: Attempts of Critical Spatial Practice,” at the Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art (NTU CCA), and “Radio Malaya,” at National University of Singapore Museum (NUS).

The former takes its point of departure from the practice of Hong Kong-born Singaporean architect William S.W. Lim (b. 1932) and the Asian Urban Lab, an initiative started by Lim and his colleagues in 2003. Curated by Ute Meta Bauer, Khim Ong, and Magdalena Magiera, this exhibition explores Lim’s many treatises on architecture and urbanism from 1950s Singapore through commissioned projects from contributors such as Laura Miotto, Mark Glode, Sissel Tolaas, Etienne Turpin, and Shirley Surya. Miotto’s Mega Living Room (2016) takes the form of a support structure in the main exhibition space, creating a living room where points of social interaction can take place. Referencing Lim’s proposal of upcycling, Miotto’s installation re-uses display elements from earlier NTU CCA exhibitions. These are interrupted by organic wall displays of quotations, quotes, articles, images, and printed material gathered in Surya’s Tracing and Placing “Incomplete Urbanism” (2016), which attempts to chart Lim’s role relative to Singapore, critical urban ethics, and activism. The idea of the urban is stretched through other tangible experiments, including Tolaas’s SmellScape Singapore 2/42 (2016), which creates an invisible landscape through the use of the olfactory sense.

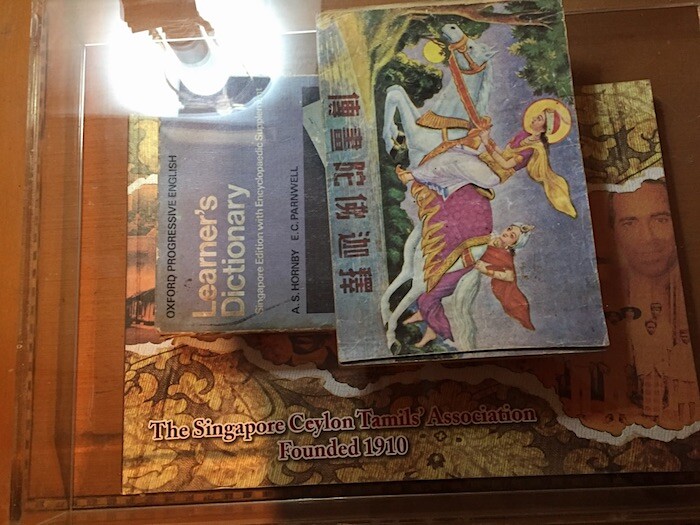

At the NUS Museum, “Radio Malaya” takes its point of reference from an earlier iteration of what is today Radio Televisyen Malaysia, a Malaysian public broadcaster. Radio Malaya existed from 1946 to 1963, the period when Singapore and Malaysia were recognized internationally as the geopolitical entity Malaya. Curated by Ahmad Mashadi and Siddharta Perez, this exhibition uses A Nation in the Making, a broadcasted radio play from 1957, written by S. Rajaratnam (1915-2006), former deputy prime minister of Singapore, as a narrative device tracing art and culture within the landscape of Malaya, appearing throughout the exhibition in excerpts as wall text. It’s a dense and complex exhibition, whose guide features archival materials referring to a 1959 meeting convened to discuss the possibility of an authentic Malayan culture, leading the viewer to a set of socialist realist woodblock prints illustrating the ambivalence of the issue discussed. Showcasing works from the National University of Singapore’s collection interspersed with contemporary artists including Debbie Ding, Heman Chong, Michael Lee, Amanda Heng, Jose Tence Ruiz, “Radio Malaya” looks at the complexities of historicizing an uneven multicultural scene through a singular (and, at times, Western) vernacular.

Reflecting back on the Singapore Biennale, it can be said that it is easy to make singular and sweeping themes from a position of privilege—governmental or otherwise. However, at the point of writing, with the increase in self-organized art spaces and tertiary education institutions in Singapore and the region, coupled with a highly developed audience, can a biennale that has so far fallen short of its touted complexity and reflexivity justify its existence beyond as a mere charade for larger political colonialist designs on the region’s art narratives?

See Pauline J. Yao, “2011 Singapore Biennale,” art-agenda, March 18, 2011, http://www.art-agenda.com/reviews/2011-singapore-biennale/, and Lee Weng Choy, “Dive Deeper—Biennales and Their Critics” in Shifting Boundaries: Social Change in the Early 21st Century, eds. William S. W. Lim, Sharon Siddique, and Tan Dan Feng (Singapore: Asian Urban Lab, 2011).

C.J.W.-L. Wee, The Asian Modern: Culture, Capitalist Development, Singapore (Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press, 2007), 158.

Yvonne Low, “Re-evaluating (art-)historical ties: the politics of showing Southeast Asian art and culture in Singapore (1963-2013)” Seismopolite, December 29, 2015, http://www.seismopolite.com/re-evaluating-art-historical-ties-the-politics-of-showing-southeast-asian-art-and-culture-in-singapore-1963-2013-i. Low links Singapore’s participation in the 1963 Southeast Asian Cultural Festival and the 2013 Singapore Biennale as gestures that would posit Singapore as “a centre of world trade and the emporium of South-East Asia.”