I was late to the Hamilton sensation, but it felt opportune to have seen Lin-Manuel Miranda’s incandescent musical a few weeks apart from the North American premiere of The Lehman Trilogy at the Park Avenue Armory, Stefano Massini’s delirious play that charts an equally distinct American narrative of immigration, capital, and indelible personalities through the rise and (still recent) fall of the famed financial institution. There’s added significance for the art world: the Robert Lehman Wing, opened in 1975, sits just 15 blocks up at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Both productions are characterized by audacious attempts at complex narratives that contextualize our current moment in broader historical frames. The approach is as clarifying as it is satisfying. Both plays also registered as affirmations of what art can achieve in a moment like this: Hamilton’s precise anti-typecast and brilliantly juxtaposed musical genres are exhilarating, while The Lehman Trilogy’s geometric, minimalist glass cube of a stage spins around in thrilling contrast to the giant, semicircular screen with its immersive media display.

As the week of Frieze Art Fair began with streams of Instagrammed and Instagrammable content, the site where a significant chunk of visual discourse unfolds showcased unique forms of art criticism—in nimble, witty memes. Despite the staged authenticity and touch-ups endemic to the platform, there is a radical sense of transparency in precisely the explicit (self-)promotional evidence of who people choose to associate with, which parties they roll through, and the level of access they enjoy (or are denied)—shown in scrolling feeds right alongside images of art. Many in the art world follow @diet_prada,1 which draws attention to lesser-known moments of fashion history to call out copycat designers and cultural appropriation offenses with laser focus (rather than tired, generalized moralizing). @bradtroemel,2 on the other hand, grills art professionals’ denial, cognitive dissonance, and complicity, inherent in navigating the neoliberal thick of things. The crisis of art’s agency continues. But Troemel’s self-deprecating (hence empathetic) humor is an easier pill to swallow than the widely quoted response from Whitney Museum director Adam D. Weinberg, who argued that the museum “cannot right all the ills of an unjust world, nor is that its role,” in light of the public outrage and continued protest at the museum following recent revelations that Warren Kanders, the museum’s board’s vice chairman, owns the defense manufacturer Safariland, which produces tear gas canisters reportedly used at the US-Mexico border against migrants.3

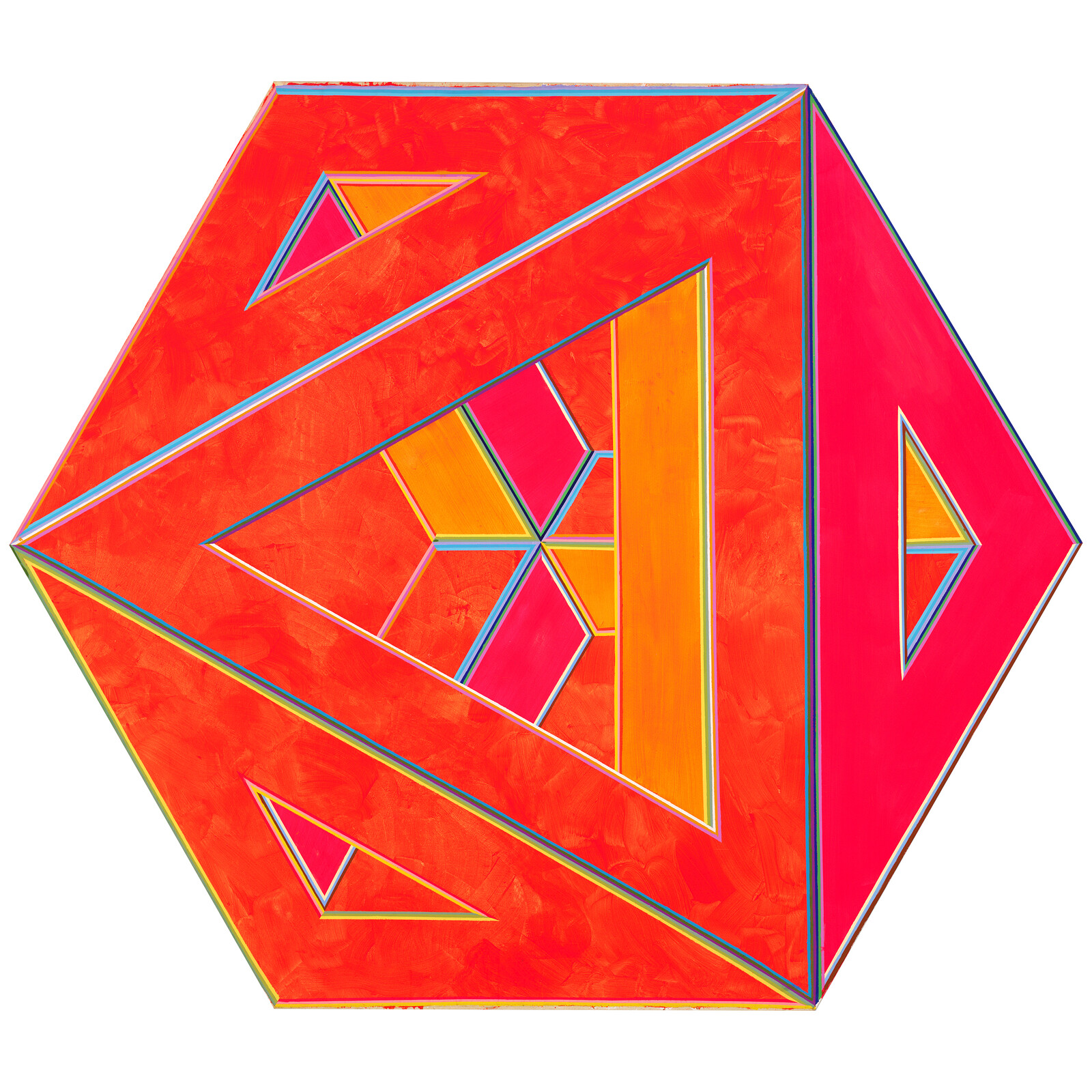

The Whitney, to its credit, is more open to dissent than most institutions. Its Saturday drop-in public forums, titled “Ethics of Looking” and initiated in the midst of the controversy surrounding Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket (2016) at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, anticipate more debates in response to the imminent new edition. But a refreshingly nuanced case-in-point can be found in the recently opened collection show “Spilling Over: Painting Color in the 1960s,” featuring various experiments with color and abstraction that went beyond the usual canonical suspects, such as Helen Frankenthaler and Frank Stella. The acquisition of work by Alvin D. Loving—the first black artist to receive a retrospective at the Whitney, and on view at “Spilling Over”—was directly tied to the effective activism of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition Inc. during the 1960s and ’70s. At the same time, artists such as Sam Gilliam were practicing abstraction, convinced of its capacity for aesthetic and political agency, in contrast to the pressure to work with figuration, to “represent,” that almost came as a mandate for artists of color.

As important as representation and diversity are, institutional programing with these goals in mind often feels frustratingly stagnant and tokenistic, particularly in the (identity) political climate of late. “The Moon Represents My Heart: Music, Memory, and Belonging,” which also opened last week at the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA), provided a timely antidote. Rather than serving up identity in dumbed-down, digestible symbols and trite metaphors, curators Hua Hsu, Herb Tam, and Andrew Rebatta were voracious with their materials. The exhibition brings together traditional regional operas practiced by early Chinese immigrants—which were already in conversation with the inchoate forms of local vernacular music and racial dynamics—with new age Chinese hip-hop. It also surveys saccharin love songs, which bound the Chinese-speaking community worldwide more potently than any ideology, in parallel with experimental works by the likes of artist and musician C. Spencer Yeh. “The Moon” is an unmissable mixtape of the season, an open invitation to jam among fellow fans, full of unexpected, campy routes to travel down. Yeh is also among the line-up of musicians invited to participate at artist Tarek Atoui’s ongoing project at Kurimanzutto New York, featuring an intricate sound-making machine—The Organ Within (2019)—that can be operated and activated in numerous, ludic ways.

A revival of camp is facilitated by the annual exhibition at the Met’s Costume Institute “Camp: Notes on Fashion” (in tandem with the Met Gala), which explores the legacy of Susan Sontag’s theorization of the concept in her 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp.’” The exhibition’s relaxed confidence and celebration of otherness resonates with the Outsider Art Fair booth’s display “The Doors of Perception” at Frieze New York, which provided compelling counterpoints, in the form of works by visionary and outsider artists, to the more detached-seeming (yet equally commercializable) searches for novelty on view throughout the sleek, sprawling fair.

A singular case of leveraging outsiderness into a celebrated canon worldwide is explored at the Met’s “The Tale of Genji: A Japanese Classic Illuminated” exhibition, a thousand-year-old tale told through rich histories of calligraphy, poetry, and visual arts from Tosa School golden screens to Waki Yamato’s wildly popular manga series, originally published between 1980–93. At the curator-led tour organized by Asia Art Archive in America, art historian John Carpenter spoke about the “psychological sophistication” of the novel—written by the Heian courtier Murasaki Shikibu in the eleventh century—that so astonished Virginia Woolf, evident in her 1925 review of Arthur Waley’s six-volume English translation for British Vogue, in which she praised the novel’s “perfection.”4 According to Carpenter, the flourishing of women’s writing of which Genji is an example coincided with the development of a Japanese vernacular that allowed for more spontaneous and sensitive expressions in literature. Highly educated women at the court were encouraged to apply this language, while their male counterparts were strictly limited to classical Chinese. This new language proved particularly conducive to sensitivity and empathy. And identifying languages that facilitate empathy is a fundamental role that art institutions—and practitioners alike—can and should play. So is enlivening institutional exhibitions with more histories and their respective canons, which will prove more productive than the mere rejection of (a Western) one.

Hrag Vartanian, Zachary Small, and Jasmine Weber, “Whitney Museum Staffers Demand Answers After Vice Chair’s Relationship to Tear Gas Manufacturer Is Revealed,” Hyperallergic (November 30, 2018). See https://hyperallergic.com/473702/whitney-tear-gas-manufacturer-is-revealed/.

Virginia Woolf, The Essays of Virginia Woolf, Volume IV, 1925–1928 (London: Hogarth, 1994), 268.

.jpg,1600)