May 11–November 24, 2019

Gemini came a little too early to Venice. While the 58th edition of the Venice Biennale was clearly born under the sign of Taurus, the exhibition’s mood is that of the mercurial twins who oscillate between opposing states of mind. Don’t let yourself be fooled by the exhibition’s title, mired in borrowed orientalist apocrypha, “May You Live in Interesting Times,” ambiguous mirroring is the true structuring principle of the show. To this end, the curator of the international exhibition, Ralph Rugoff, played his two houses—the Arsenale and the International Pavilion in the Giardini—against each other by having each of the participating artists present work in both venues. The effect of this maneuver creates an odd form of creative bookkeeping wherein 79 artists are stretched to perform the work of 158.

Rugoff’s…

“Now that machines can predict the future, the present has turned unpredictable.” These cautionary, paradoxical words are spoken in Hito Steyerl’s video installation Power Plants (2019): a forest of standing screens showing time-lapsed blooming flowers and growing cacti. The accompanying voiceover further warns that “our lives rely on what we cannot see”: from pollution-clogged photosynthesis to overactive AI algorithms. Power Plants’ combined concern for the diminishing natural world alongside today’s digital excess and ennui recurs throughout the Biennale. The carcass of digital promise turns up everywhere, from Neïl Beloufa’s barebones computer stations (Pre-Post 1–2, 2019) to the unprotected tangle of wires behind Steyerl’s screens in Leonardo’s submarine (2019),…

Gemini came a little too early to Venice. While the 58th edition of the Venice Biennale was clearly born under the sign of Taurus, the exhibition’s mood is that of the mercurial twins who oscillate between opposing states of mind. Don’t let yourself be fooled by the exhibition’s title, mired in borrowed orientalist apocrypha, “May You Live in Interesting Times,” ambiguous mirroring is the true structuring principle of the show. To this end, the curator of the international exhibition, Ralph Rugoff, played his two houses—the Arsenale and the International Pavilion in the Giardini—against each other by having each of the participating artists present work in both venues. The effect of this maneuver creates an odd form of creative bookkeeping wherein 79 artists are stretched to perform the work of 158.

Rugoff’s display is likewise dotted by recombinant forms as salient features of works are meant to act as anchors, but end up flattening the art into objects grouped rather glibly by kind or theme as opposed to intention, code, or context. For example, repetitions of sculptures based on the same source material such as Arthur Jafa’s series of chained monster truck tires, “Big Wheel” (2018), that I read as throwing shade on toxic masculinity by putting it on a gallows, or even worse, which are parroted in the Arsenale by Yin Xiuzhen’s Nowhere to Land (2012), a large-scale installation in which a scrapped-together semblance of an upturned airplane’s landing gear stands in as some sort of quixotic cypher of how China’s breakneck development is shaping a country that becomes unrecognizable if you leave it for even a day.

This is not to say that the curation totally evades richly textured dialogues. Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s Walled Unwalled (2018), a video work revolving around a set of acoustic case studies in which legal evidence was gathered by spying through walls, floors, and other structures, is considered alongside another work in the International Pavilion: Teresa Margolles’s Muro Ciudad Juárez (2010), a literally scarred wall removed from its titular city to serve as a silent witness for the spate of violence stemming from the Mexican drug war and other related forms of systemic terror across the region. Instead of reveling in the dark poetics of this clever partnering, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s Can’t Help Myself (2016), a rather heavy-handed one-liner on automation centered around a caged robotic arm that is algorithmically programed to endlessly mop up fake blood in vain is plopped next to the Margolles in one of the exhibition’s worst fixed marriages.

With the inclusion of artists from dozens of different nationalities, the show appears diverse and its roster represents gender parity. Identity and visibility likewise play a central role in the themes of many of the works such as those by Kahlil Joseph (BLKNWS, 2018–ongoing) and Tavares Strachan (The Encyclopedia of Invisibility (white), 2018) in addition to those by Jafa. This hides the simple fact that the majority of the artists represented actually live and work in a just a few European and American cities: Berlin, Paris, Los Angeles, New York. Whether these tethers tie down new forms of geographic or socio-economic bias or not, their preponderance suggests how globalism’s alpha cities increasingly syphon more and more resources from elsewhere while these hubs run the risk of converting artists into cultural “Davos” men and women whose stock and trade is closer to multinational corporatism than to internationalist solidarity. By way of accident, Rugoff’s garish use of raw plywood museum walls throughout the Arsenale transforms the proverbial white cube into an even more banal and troubling reference: the construction boarding that anticipates gentrification and homogenization. Let us hope this material is later recycled, but then again, it will most probably serve the depressing function of shoring up Venetian facades that are rotting inside out due the increasing floods that drench the city in salt water. This makes me wonder if viewers are meant to empathize with Yuan and Yu’s robot as some form of metanarrative on preservation, which shows, to misuse another often-misattributed quotation, how insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, expecting different results. This Sisyphean folly is strongest not in the international exhibition but in the national pavilions, where artists and audience are repeatedly asked to reinforce the idea of the nation-state. Take for example both the French and German Pavilions, which imitate each other, only with different aims.

Both pavilions tour audiences in through the back door and begin by creating a scenography of sneaking into countries. Laure Prouvost’s project for the French Pavilion, “Deep See Blue Surrounding You / Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre,” is primarily a bohemian romp where wanderers and performers document their travel from northern France to Venice to produce and acquire various surreal artifacts such as breasted jellyfish made of Murano glass, which line the rooms of the pavilion. The ultimate effect is to ape the clichéd idea that it’s the journey and not the destination that builds the traveler’s character. Yet a much more prescient politics hits home as the basement entrance reveals a symbolic underground passage the formerly London-based artist was digging to create a pantomimed Channel Tunnel linking the French Pavilion to the nearby British Pavilion in the time of Brexit. Across the way in Germany, Natascha Sadr Haghighian, working under the Germanified misspelling of her name, Natascha Süder Happelmann, slips visitors in through the rear as a commentary on migration and the inhumane attempts to hem the movement of people. I rather enjoy aspects of the work, such as the artist’s attempt at anonymity by wearing a rock as a mask over her head and face when in public. I am, however, rather ambivalent about the pavilion’s beguiling airtight hermeticism of encrypted references surrounding the history of whistles being used by security agents and protesters alike, somehow turning into a vague dog whistle on the subject of authority sounded by speakers attached to a rigid steel scaffolding supporting a leaking dam, a sort of blunt détournement of jingoist metaphors.

While the bugbear of national insecurity and its daft manifestations are incredibly necessary to unpack in today’s rising tide of reactionary politics, few subjects demand constant attention more than climate change. Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė’s opera Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019) in the Lithuanian Pavilion reflexively soaks in the contradictions of climate concerns until its fingers and toes get wrinkled. Visitors are led to a nondescript warehouse building, where from a second-floor viewing gallery they look down at performers in swimsuits populating an artificial beach. The effect is nothing less than ethereal as viewers are placed in the privileged position of observing the characters from a godlike bird’s-eye view while being privy to the performers’ internal thoughts as the opera’s songs are sung by detached and soul-searching leisure seekers as if they are soliloquies fretting the exhaustive task of speaking about our definite extinction. Loaded with gravitas, the general malaise of this black comedy, which eschews plot for affective rambling, traces a fine line in which despondency straddles quietism. Likewise, the everyman aesthetics of this Bruegel on the beach is predominantly portrayed by Caucasians, which, if considered as satire, presents a sea of white people handwringing about how they are destroying the world while on vacation instead of doing the hard work of fixing their own mess.

Returning to Gemini, the sign stresses the twinned nature of communication as intelligence can easily lead to deception, or how adaptability is also the bedfellow of cunning. Dualism reminds us that action is neither all good or all bad, nor is it neutral. While many great philosophers have tried to crack this old chestnut, I’ll just leave you with a simple question: Is the biennale model really that interesting?

“Now that machines can predict the future, the present has turned unpredictable.” These cautionary, paradoxical words are spoken in Hito Steyerl’s video installation Power Plants (2019): a forest of standing screens showing time-lapsed blooming flowers and growing cacti. The accompanying voiceover further warns that “our lives rely on what we cannot see”: from pollution-clogged photosynthesis to overactive AI algorithms. Power Plants’ combined concern for the diminishing natural world alongside today’s digital excess and ennui recurs throughout the Biennale. The carcass of digital promise turns up everywhere, from Neïl Beloufa’s barebones computer stations (Pre-Post 1–2, 2019) to the unprotected tangle of wires behind Steyerl’s screens in Leonardo’s submarine (2019), and Lee Bul’s Aubade V 50% (2019), an empty tower of blinking LED lights and naked circuitry. Roman Stańczak has seemingly crashed an airplane brimming with computer debris in the Polish Pavilion (Flight, 2019), while in the Japan Pavilion (“Cosmo-Eggs,” by Toshiaki Ishikura, Fuminori Nousaku, Motoyuki Shitamichi, and Taro Yasuno), twinkling machines overhead are fed by clear plastic tubes, like digital technology on life support.

This biennale spreads out wider and bigger than ever, with 90 national pavilions and 21 official collateral events—including the first-ever official performance program, co-curated by Aaron Cezar—plus countless piggybacking shows citywide. In the main exhibition, “May You Live in Interesting Times,” artistic director Ralph Rugoff crams multiple works by 79 artists in a willfully overhung installation. The most rewarding works ride the information overload, such as Golden Lion–winner Arthur Jafa’s compelling video collage The White Album (2018), which gathers (among other things) online examples of white guilt, conflict, and race-specific subcultures: from tough goths displaying virtuoso mosh-pit dance moves to a crazy-eyed marching-band drummer. Kahlil Joseph’s engrossing video diptych, BLKNWS (2018–ongoing), presents found footage often showing black triumph and renewal, such as the 2018 election of 26-year-old Mariah Parker as county commissioner in Athens, Georgia, sworn in with her hand placed on The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) in lieu of a Bible.

High-octane artworks like these, at home amid the exhibition’s relentless intensity, thrive. Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s massive robot arm (Can’t Help Myself, 2016) encased in its own room-sized Perspex box labors incessantly to control a puddle of blood-red paint, like a caged RoboCop amputee armed with an industrial-sized paintbrush. Quieter moments struggle to be heard but merit discovery. Suki Seokyeong Kang’s series of delicate geometric constructions “Grandmother Tower” (2011–13) rise above viewers with elegant lightness, while Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s interiors and group portraits represent this biennale’s most accomplished painting. Magnificently drawn, collaged, and colored, these works recall Richard Hamilton’s claustrophobic interiors—if combined with domestic warmth and rich texture absent in 1950 and ’60s Pop. Rugoff gathers a convincing selection of artworks representing questions around race, climate catastrophe, artificial intelligence, armed conflict, borders, and poverty, although some insiders complained that too many artworks had already been seen elsewhere. I’m willing to forgive the overhang for the sake of so much terrific art, but some confusing overcrowding is inevitable. In the International Pavilion at the Giardini, the large top space seems curated by scatter gun, with an odd alternating sequence of paintings by Henry Taylor, Julie Mehretu, and George Condo, plus a monumental marble work by Jimmie Durham (Black Serpentine, 2019) languishing in the corner. More successful combinations include Cyprien Gaillard’s tiny, holographic, flickering dragon, projected on an electric fan (L’Ange du foyer (Vierte Fassung) [Angel of the Home (Fourth Version)], 2019), ceaselessly morphing beneath Danh Vo’s mirror paintings Suum cuique (2019). Along with Yu Ji’s fragmented body-part sculptures series “Flesh in Stone” (2013), this dome-like space (the pavilion’s former grand entrance) offers a dark and magical sideshow.

Pavilions focusing on coherent solo presentation contrast well with the central exhibition’s excess. These include Martin Puryear’s distinguished representation of the United States, “Liberty / Libertà.” The pavilion is partially in remembrance of Sally Hemings—a slave owned by Thomas Jefferson, whose home, Monticello, inspired the pavilion’s architecture—who is widely believed to have been the mother of at least four of his children. Or the Belgian Pavilion, “Mondo Cane,” by artists Jos de Gruyter and Harald Thys, with its comical, Disney-ish tableau of animatronic figures reviving old-timey male archetypes, such as cobblers and spinners, alongside new models including psychopaths and zombies. Similarly, expertly curated offsite solo shows including “Jannis Kounellis” at Fondazione Prada and Helen Frankenthaler’s “Pittura/Panorama” at Palazzo Grimani offer a welcome relief for overtaxed senses.

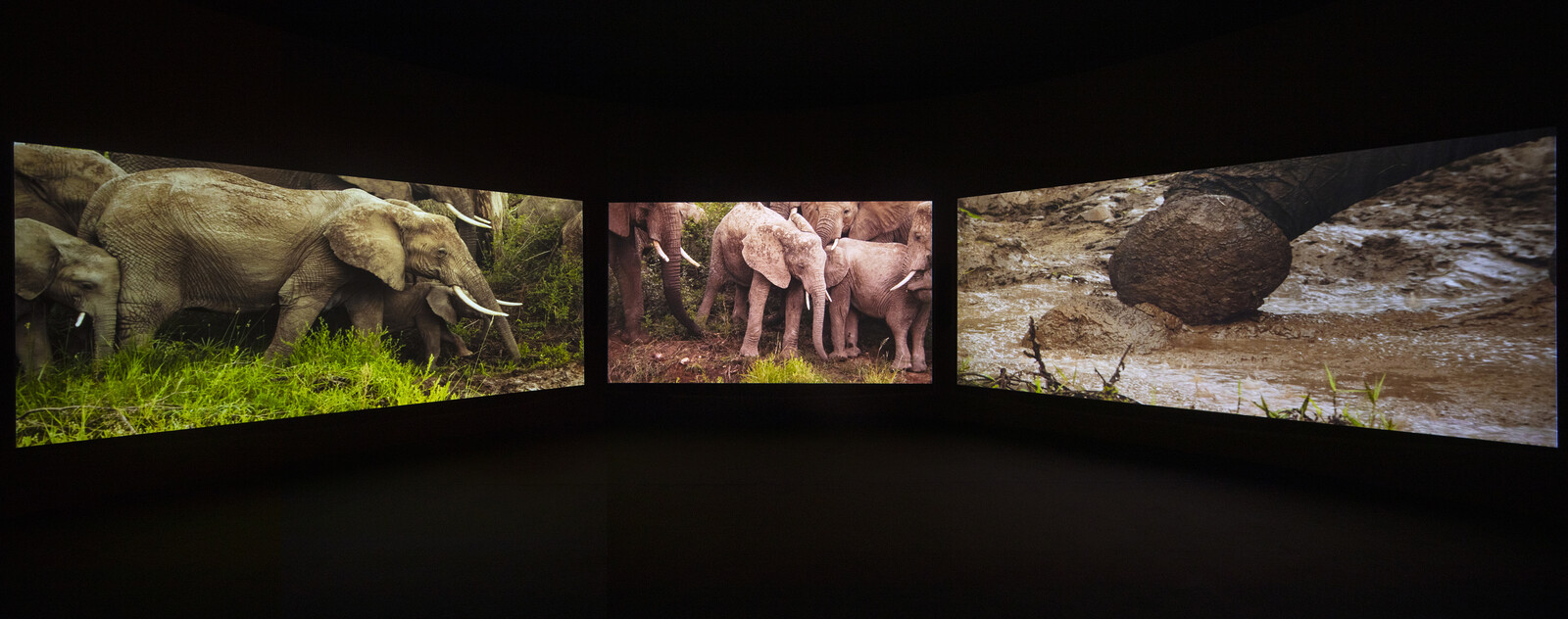

The curving, sand-colored Ghana Pavilion, designed by architect David Adjaye, houses at its center a suite of nine sensational portraits by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Adjacent to these is John Akomfrah’s three-screen video The Elephant in the Room – Four Nocturnes (2019), in which images of lush jungle, herds of elephants, and sweeping flocks of birds alternate with vintage photographs of imperious colonials, who showed their appreciation for Africa’s natural beauty by plundering all they could. At the pavilion’s entrances are three of El Anatsui’s enormous, spectacular curtains, which alchemically transform discarded bottle-caps into a weightless shimmer of geometric beauty, and Ibrahim Mahama’s equally monumental wall-sculpture A Straight Line Through the Carcass of History 1649 (2016–19). Completing “Ghana Freedom” were studio portraits by Felicia Ansah Abban, the nation’s first female professional photographer, and video sculpture by Selasi Awusi Sosu (Glass Factory II, 2019). The powerhouse Ghanaian debut became the visual and conceptual anchor of the Arsenale, setting the bar high for national pavilion group shows probably for many biennales to come.

Walls—whether literal or symbolic—rose and fell everywhere. (No prizes for joining the dots between these and Trump’s Mexican folly or Brexit.) Teresa Margolles installed the cement-block and barbed-wire Muro Ciudad Juárez (2010), while the metal, automatic gate of Shilpa Gupta’s Untitled (2009) gradually demolishes the wall behind it with every crashing close. Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s video installation Walled Unwalled (2018) tears down walls not just brick-by-brick but atom-by-atom, via the artist’s investigations into cutting-edge probe technologies able to “see” and “hear” through walls, leaving citizens literally defenseless. Natascha Süder Happelmann’s German pavilion features an enormous, two-story high “concrete” dam, while the Italian pavilion is an over-constructed maze of walls, a daring if inhospitable experiment by curator Milovan Farronato. Subtler divisions include the sliding, fringed silver curtain at Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz’s Swiss Pavilion “Moving Backwards” separating viewers from a troupe of brilliant onscreen dancers, themselves pulling down barriers across genders and genres, from art-performance to disco seduction. In “Time Forward,” an offsite group show at the V-A-C Foundation curated by Omar Kholeif and Maria Kramar, Christopher Kulendran Thomas and Annika Kuhlmann’s Being Human (2019) erected a transparent screen that divides the gallery in half, separating the audience’s space from an off-limits, insipid art exhibition of dull paintings and sculptures. Onscreen, talking heads rethink the logic of ye olde “contemporary art”—that antiquated art genre that briefly flourished in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries—and its collusion with economies catering to the individual over the collective.

Another leitmotif was the sea, beginning with Joan Jonas’s Moving Off the Land II (2019) performance at Ocean Space, with its glowing footage of sea life in public aquariums accompanied by the artist reading from texts by Rachel Carson and Peter Godfrey-Smith’s Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea and the Deep Origins of Consciousness (2016), among others. Laure Prouvost’s French Pavilion “Deep See Blue Surrounding You / Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre” also took viewers on a tentacular, 28-minute video-journey comprised of rapid-fire images that shift from octopus-filled tide pools to the built-up outskirts of Paris, all accompanied by a delightful cast of characters of multiple ages, genders, and races. “You are one with your neighbor,” whispers Prouvost, inviting viewers to join together in a spirit of celebration and joy otherwise rare at this sober biennale.

The Lithuanian pavilion’s operatic Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019) by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė, curated with pitch-perfect attention to detail by Lucia Pietroiusti, deserved its surprise Golden Lion win. (Bookies predicted Prouvost, with Ghana a strong second bet.) Filled with 35 tons of sand, beach umbrellas, towels, and about a dozen swimsuited performers at a time, the ground floor of a former dockside warehouse has been converted into an artificially sunny walled-in beach of the future when, presumably, few open beaches remain. While dogs scamper and children play below, viewers gaze down from a first-floor balcony at the lounging performers as they launch into song, each singing in turn a personal tale before joining together in harmony. Viewers peer down at this bright, sandy tableau from above, as if the lid of some giant magical music-box has been lifted to reveal a secret seaside chorus hidden inside. Having absorbed the work’s warnings about complacency in the face of planetary disaster, viewers may never again lie on a beach without hoping the crowd will suddenly break into thoughtful, exquisite song.

,%20opera-performance,%20Biennale%20Arte%202019,%20Venice%20©%20Andrej%20Vasilenko.jpg,1600)