“If I don’t find what I want on the first page, I’ll usually just give up,” stated the American interface designer Aza Raskin in 2006.1 He later came to be known as the inventor of the infinite scroll—for which he recently publicly announced his regret.2 While Raskin’s interface dominates most digital media today, The Otolith Group’s Anathema (2011) brings us back to a distant time in the mid-2000s when the first iPhones hit the market. In an abstract montage of moving images from early YouTube, advertisement for touchscreen devices blend in pixelated abstraction, enabling a sublime imaginary of something beyond the responsive screens that we depend on. Much earlier, in the late 1970s and early ’80s, Swedish artist Charlotte Johannesson transferred weaving to the few pixels of Apple’s first home computers. This was before conventional printers, so Johannesson had to hack large-format architecture printers to get her colorful abstractions on paper.

The transition of ideas through matter has always been central to aesthetics. Ursula K. Le Guin has written that “technology is the active human interface with the material world”3—it is the materialization of an interface that manifests each time we touch a screen, a stone, or each other. At Moderna Museet, curator Lars Bang Larsen borrows the title of Le Guin’s essay “A Rant About ‘Technology,’” combined with an early technological work by Robert Rauschenberg (Mud Muse, 1968–71), for an exhibition that seeks to investigate how the “active human interface” Le Guin discusses manifests in contemporary art.

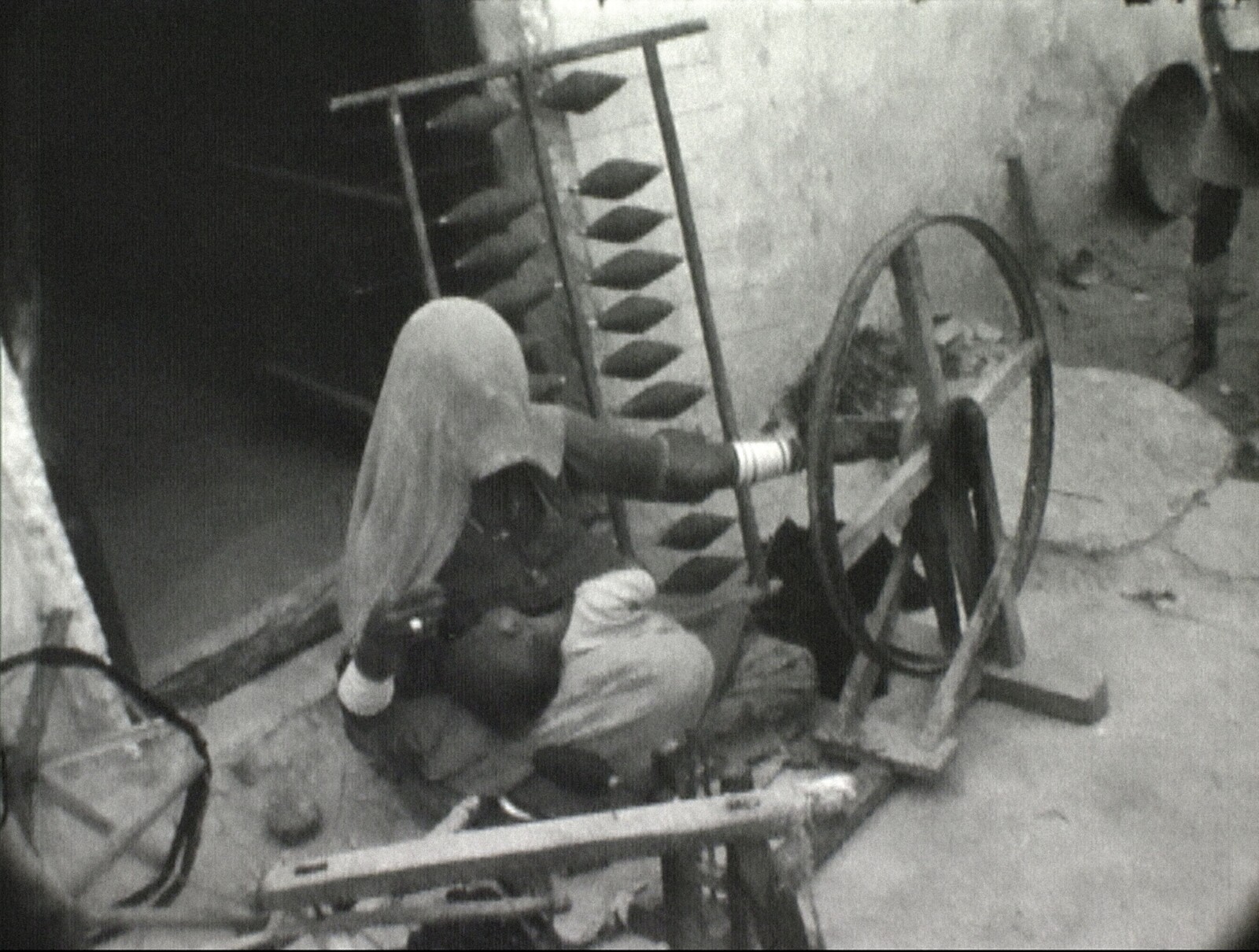

Central to the exhibition is the transitory state between presence and absence, be it ocular, social, or spiritual. The exhibition draws attention to the social capacity of humans to encounter, translate, and emit, and communicates that this is not only a concern of the Western avant-garde or of Silicon Valley, but an international continuum. As a consequence, the exhibition features works ranging from the 1950s to the present day and from many parts of the world. On view near the entrance to the show, Rauschenberg’s Mud Muse, created in collaboration with engineer Billy Klüve, a large basin full of a thick mud-like liquid made of water mixed with bentonite bubbles as if it had something to say. (In fact, its control console remixes the sound of the audience with its own gurgles.) While Rauschenberg’s involvement with Experiments in Art and Technology in the late 1960s is inscribed in art history, similar endeavors are less discussed, for example The Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW) in Delhi and Mumbai, initiated by Indian artist Akbar Padamsee and active from 1969 to ’74. VIEW was a pioneering interdisciplinary collaboration of artists and thinkers, among them Nalini Malani, whose video Taboo (1973) is included in the show. In a short loop, the hands of a young woman tinker silently, as she crouches outside of what seems to be a factory, where no women were allowed to set foot.

In an essay on Malani’s work, curator Nancy Adajania makes a claim that could be extended to the exhibition as a whole: “new media art […] is dependent on the technological advances and the politics of communication as they prevail in that locale.”4 With these geopolitics as a backdrop, Adajania suggests the term “new context media” for media that is particular to its local scene. “Mud Muses: A Rant About Technology” proves her point, while emphasizing the collective aspects of such media, as most of the featured artists work in groups. One example is the South African CUSS GROUP, who in their video installation Kumnyama la/It’s Dark Here (2019) bring attention to a basic infrastructure of modern society: electricity. CUSS GROUP’s method integrates interviews and handing over the camera to their subjects and for this work they interview hackers who surreptitiously connect to the electricity network in an attempt to illuminate dark zones in suburban areas. Projected on a small house constructed of semi-transparent plexiglass inside the exhibition space—which refers to the shortage of housing in Johannesburg—the video reveals the danger of electric hacking. A doorless opening reveals that the structure is full of desert sand. It’s an imaginary oasis. Around Johannesburg, where the members live and work, the segregation of resources is not new, but, as the video communicates, it’s seemingly never ending.

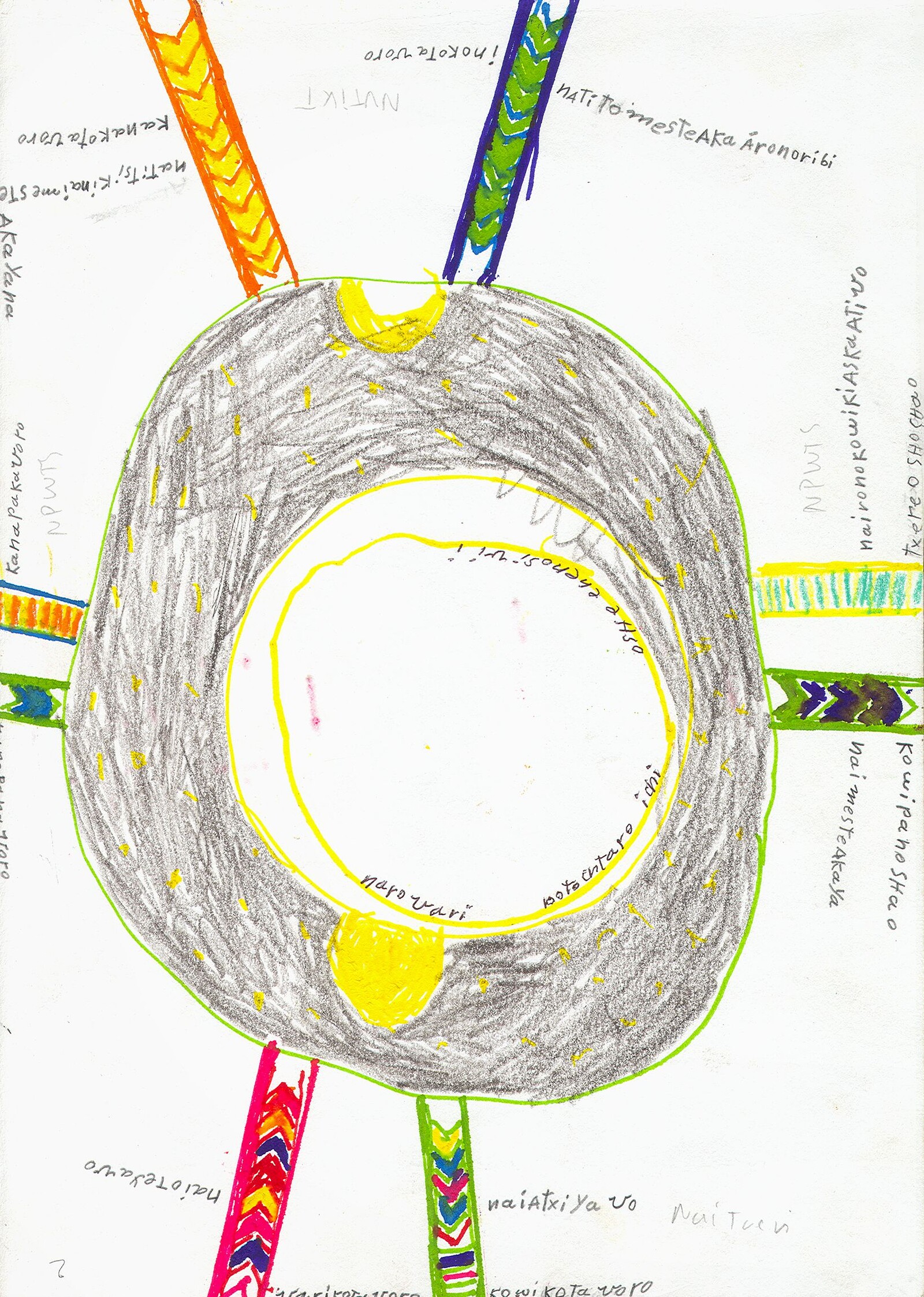

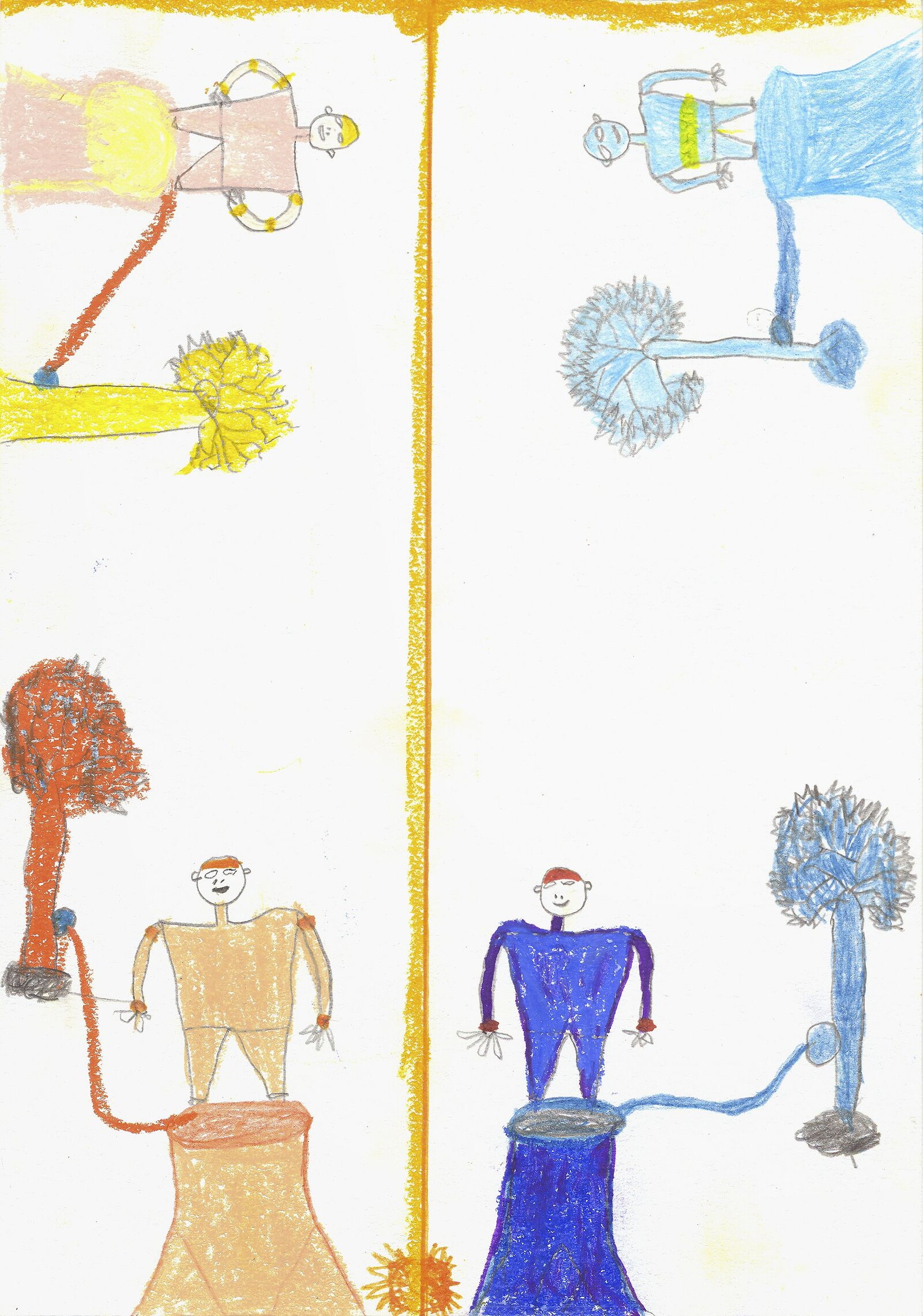

At the center of the exhibition is a collection of narratives about life and death, exhibited in vitrines. A decade has passed since the Marubo shamans Paulino Joaquim Marubo, Armando Mariano Marubo (who passed away in 2017), and Antonio Brasil Marubo donated these drawings to anthropologist Pedro de Niemeyer Cesarino, who compiled them under the title Cosmograms/Marubo Drawings (2004–09). While the drawings manifest Bang Larsen’s interest in the materialization of the social beyond a Eurocentric spectrum, the Western authorship remains unquestioned—the Marubo drawings aren’t contextualized as aesthetic objects with any intention of their own. Instead of allowing the active human interface Le Guin discusses, their inclusion is a reminder that the aesthetics of media are closely related to a colonial history in which systems of knowledge and creativity are homogenized by means of domination and exploitation. And if it is through interfaces that society mediates itself, the question is who serves as medium, who governs the message. Only when the medium and the mediator are considered together can new context media have an impact that lasts beyond the site of the museum.

Aza Raskin, “No More Pages,” Humanized (April 25, 2006), https://web.archive.org/web/20120606053221/http://humanized.com/weblog/2006/04/25/no_more_more_pages/.

Tom Knowles, “I’m so sorry, says inventor of endless online scrolling,” The Times (April 27, 2019), https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/i-m-so-sorry-says-inventor-of-endless-online-scrolling-9lrv59mdk.

Ursula K. Le Guin, “A Rant About ‘Technology,’” 2004. See http://www.ursulakleguinarchive.com/Note-Technology.html.

Nancy Adajania, “New Media Overture Before New Media Practice in India,” Domus vol. 36 (2015): 35.