The first thing Jacolby Satterwhite showed me when I visited his apartment in Brooklyn was his painting studio. Leaning on walls and furniture and easels were a dozen canvases in various states, some based on family snapshots, others scenes from the mind-bent digital worlds for which he’s known. On the surface, it’s a wild departure from the works that made his reputation as a multidisciplinary artist: video installations, virtual environments, performances, and digital-media works, informed by queer theory, video games, and much else besides.

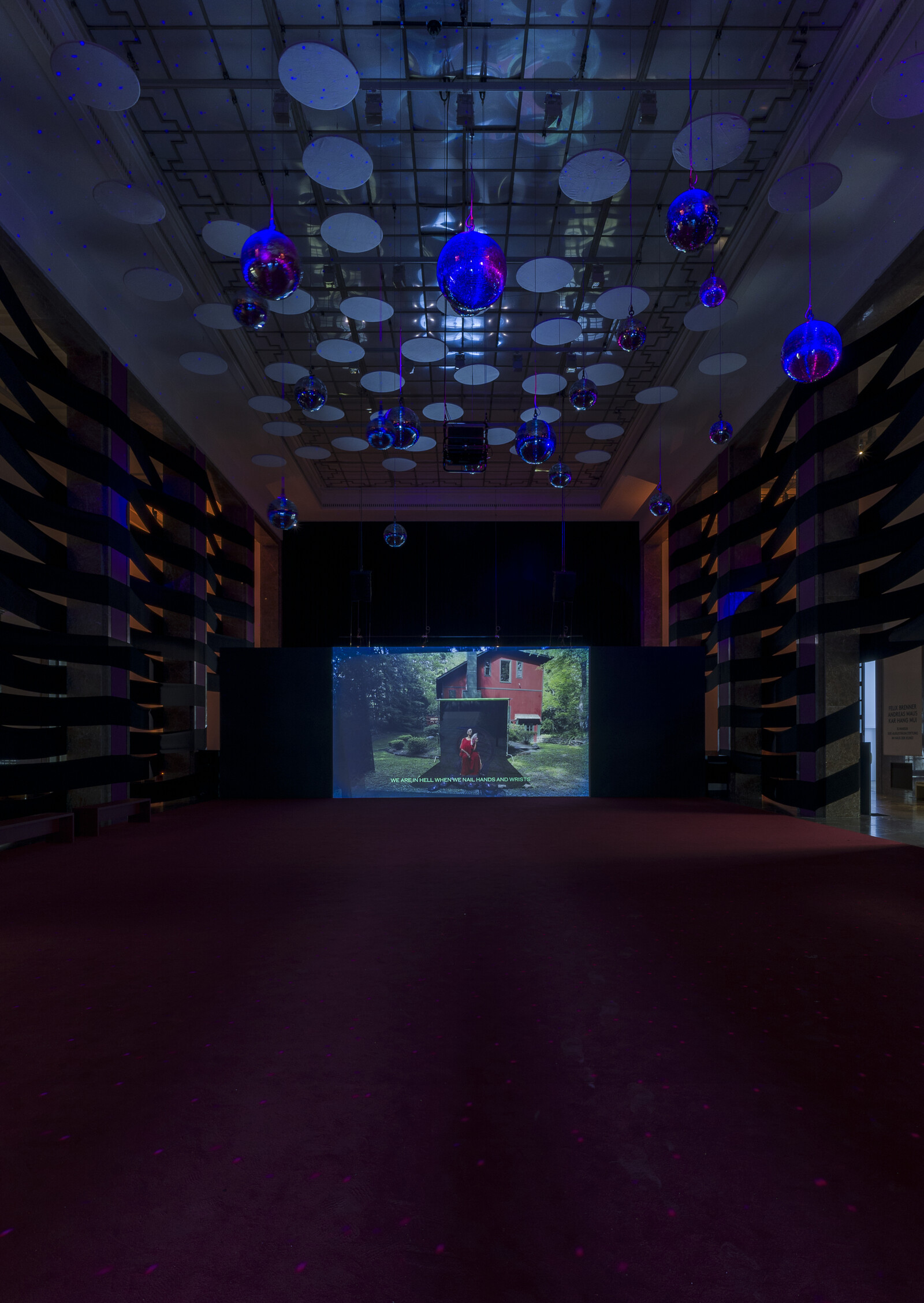

“Spirits Roaming on the Earth,” a decade-deep survey of Satterwhite’s work now on view at Pittsburgh’s Miller ICA, showcases videos, sculptures, and c-prints drawn from these idiosyncratic, alternative realities. They are populated by dancing sprites—many of them avatars embodied by the artist, others figures cast from clubs or pop culture—adorned with 3D tracings of his mother Patricia’s many schematics for fantastic household objects. Satterwhite’s Reifying Desire 1–6 (2014), his earliest series of video installations, weaves together light S&M, Patricia’s inventions (including a remote-controlled penis), and five gyrating figures modelled on Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Ropes of light flow from the characters’ hands.

Spend a moment with these videos with painting in mind, however, and the transition’s logic comes through. Satterwhite has painted before—in his stairwell are two early works, one a saturated, spectrum-laced portrait group, another a large charcoal rendering of St. Thomas probing Christ’s wound, flecked with foil hearts—and he’s painting in earnest now. But he really never stopped. “That show is a decade of me doing mood boards for painting,” says Satterwhite, “a decade of me playing with different rhythms and systems and possibilities within digital space. I feel like I’m just playing jazz now.” Alongside his survey at the Miller ICA, he’ll be a 2020–21 a Maker Resident at The Studio Museum in Harlem and is working on a computer game for Cleveland’s FRONT International in 2022.

Travis Diehl: What made you feel like you could paint again?

Jacolby Satterwhite: I was trying to get to that the whole decade. My digital, conceptual, and performance projects are my studies, my foundation for building a painting. Painting’s formalism shows up in the films, pigment prints, and the way that I exhibit them on the wall. When you’re working in the Autodesk Maya software, it feels like you’re painting because every color, every texture, every grid, the light, and the chiaroscuro… you have to choose them by hand.

And I hate my computer now. I resent it. Sitting down for 8 to 12 hours a day makes my spine hurt. Painting has brought me back. I feel like I’m in The Secret Garden (1911). Once I started painting again, at the beginning of this year, I started to look at other people’s work with much more empathy. I wanted to reach into the world and have deeper conversations with others. It’s almost like I became domestic.

TD: When you talk about the last 12 years being practice, it sounds like a traditional, even modernist way of thinking about art. There are finished works, but they feel like independent products of the artistic process, a fermentation that is happening inside the artist at all times. When is it done?

JS: First of all, between 2015 and 2021, I had some insane deadline to work towards every year. I try to get as much out of each new piece until the second day of the exhibition where it debuts. So, the first day, usually my film has this demoed, “alt” render—but no one notices. The worst was “Blessed Avenue,” at Gavin Brown in 2018. I had some technical issues and they had a three-minute clip up for three days. And then on day four, it was the full 19 minutes.

But it’s not just me moving around aimlessly and thinking, “Oh, that looks good here.” There is a method. I know what I’m trying to achieve. I make eight elaborate digital spaces, and render them. I meditate on those eight tableaus. I write around them. And then I bridge these eight images, these eight big worlds, and make them come together as one harmonized narrative. There’s point A and point Z. Everything that happens in the middle is just what makes it complicated and long and weird. But within those methods, there’s so much abstraction, confusion, and subjectivity. I don’t want to tell you anything, but I want to create a sort of blurry mirror for the viewer. It’s like a psychedelic Rorschach test.

TD: That seems related to your use of religious themes, or art history in general. There’s the Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) riff in Reifying Desire (2014). Caravaggio’s Doubting Thomas (c. 1601–02) appears in the early charcoal drawing above your stairs, and in other works since. How do you think about those weighted tropes in the context of such superficially contemporary, bright, computer-rendered visuals?

JS: It’s earnest. I was raised in the Southern Methodist church in a really intense way. I’m not religious, but it’s still in my bloodstream. I’ve been massaging my obsession with St. Thomas, the skeptic, for so many years, and I’ve realized that I have a public and a private relationship with this composition. As part of the public relationship, the mediums that I’m working in—cyberspace, digital space, animation, and the internet—are battlegrounds for misinformation and organizations such as the FSB and Cambridge Analytica, who manipulate artificial intelligence to make deepfakes and mold collective societal consciousness. So it’s an allegory of our time.

The private relationship is that I think of science as a disruptor. I had cancer when I was ten years old and had two years of chemo. There’s all this metal in the middle of my arm, and I can only move it so much. I was a rigorous draftsperson at the time, that was all I liked to do. That drawing of Madonna in the kitchen was the first thing I made when I tried to use my arm. Ever since then, I had this freight-train ambition to create, create, create. These machines, these new technologies and phenomena, kept me alive. I thought my mortality was a fraud. I was skeptical. And so I kept making these art objects to redact the doubt, to leave something behind as a way of having immortality, I guess. I hate it to sound so self-centered.

TD: You frequently use yourself in your renderings, and the cover of the catalog for the Miller ICA show is a picture of you.

JS: I know how that cover looks. But a friend I really trust was like: “You should just be bold.” I was known in school as a painter. But when I shifted into a professional sphere, everything was centered around my performance art. My body was a conduit and a medium to all the messages. I felt like I could be like Cindy Sherman, build all these costumes, and make different avatars to play with. They’re like fonts. I don’t think of myself as a protagonist in the work. I think of myself as a character, period, comma, exclamation mark.

TD: Maybe there’s a part of the work that’s about you and your self-expression, and then there’s your appearing in the work—and those things are distinct.

JS: The push and pull comes from using source material that I don’t believe in conceptually. In Birds in Paradise (2019), I appropriate the lyrics of songs my mom wrote and recorded herself, before her illness really took over. They seem so didactic and moralizing, but the work is very removed. I’m not a “We are the World” kind of guy. But how do you take such sledgehammer, didactic storytelling, and flip it upside down into something that’s unexpected and thoughtful? Using myself is the same.

TD: Or using your mother’s drawings, like the one titled The American Dream which features a picket fence. The way she renders objects in her drawings is also a bit digital: they’re composed of diamonds and triangles.

JS: Have you seen those cat drawings by Louis Wain? Schizophrenia does something to the way you process everything. The logic around everything is reoriented. My mom found solace in organization, it was medicinal for her to draw gridded patterns all day.

I’m going to tell you the whole story. Her schizophrenia became full-blown when I was around 10—I had cancer and she started talking to herself alone in a room. The Make a Wish Foundation offered me the chance to meet a celebrity, or whatever. I was like: “I don’t want to meet a celebrity, I want a computer.” This was in 1998 or ’99. I was from the hood. Nobody in my neighborhood had a computer. I felt like a star. I had a Pentium Gateway PC with a dial-up modem.

But then my mom became obsessed with the chat rooms. On shows like 20/20 and 60 Minutes, they used to talk about how the latest clinical disease in American suburbia was an obsession with chat rooms. That was my mom. She was the queen of two rooms. She had this whole persona—a mother goddess of love, Miss Cleo kind of thing—and she developed an online following. She was always writing pseudoscience, pseudophilosophy. It was very Marianne Williamson. Her name was Chatty Patty.

But the computer was in my bedroom. I had no privacy. In a bratty moment, I wanted my new toy back. Because of my mother’s mental illness, arguments were more volatile than they should’ve been. She was like: “Well screw you and the computer. I have these people with me anyway.” And so she went into the living room—I was 11 or 12—and there was a thunderstorm. She started talking to these screen names and she didn’t stop for the next twenty years.

TD: There’s a romanticized view of the mentally ill in general, and schizophrenics in particular, as being free from or beyond society because their filters and social conditioning break down.

JS: My favorite art-historical movements are Fluxus, Dada, and Surrealism, which were all about trauma. They were resisting the propaganda and lies—delivered through centuries of painting—that led to the World Wars and the dark modernity that they operated in. So they introduced chance and performance and spontaneity. And I felt as though my mother was also rejecting something by making these drawings, almost like performance scores for a potential future. I used to walk around in the woods, literally performing the drawings as scores.

TD: Are you influenced by drug culture at all? The way you’re talking about schizophrenia parallels the rhetoric of the psychedelic revolution of the sixties and seventies.

JS: People ask me that a lot. Let’s just say my videos were a lot crazier before I tried any crazy drugs.

TD: How else has the work changed over the course of these twelve years?

JS: I’m less apologetic now. I’m not afraid to make something for making something’s sake. I just work. My survey at Miller ICA was supposed to open in 2019, and I wanted that kind of show just so I could wrap it up and transition to other things. But now, in 2021, I’m deeply into other things already, like painting, and working in a way that no one’s seen yet. I’m going to do this mid-career residency at the Studio Museum, and I’m going to use it to do a 180, or what the public will perceive as a 180.

TD: And you’re also making a video game?

JS: I’m making a side-scroller game for the FRONT International 2022 in Cleveland. During the lockdown, I taught myself C++. I learned enough to know that I can never make a video game by myself. So it’s going to be simplified. But it’s a painting process. In the eighties, Japanese game-makers would paint all the assets on grids and then they’d scan them into the computer and code them from there. I want to paint all the characters, all the walk cycles, items, all the landscapes, foreground, background, and middle-ground, separately, and then composite them. Like Castlevania (2017) or Donkey Kong Country (1994).

TD: Donkey Kong Country is beautiful.

JS: All those side-scroller games are like really sophisticated illuminated manuscripts. It’s a synesthetic way of making sense of the world. So, at some point, I’m going to make the game the way I really want to. I just need six years.

Jacolby Satterwhite’s “Spirits Roaming on the Earth” is on show at Miller ICA at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, through December 5. He will be a 2020–21 Artist-in-Residence at The Studio Museum in Harlem and his work is forthcoming in the FRONT International 2022, Cleveland.