A few days before I visited the Pinacoteca, I witnessed a traffic accident. At a busy intersection in downtown São Paulo—medics and military police already in attendance—a motorcyclist lay on the oily tarmac, his crumpled bike to one side. He was going to survive, it seemed, but his recuperation might take a while. Particularly telling was the fluorescent orange food delivery box abandoned on the ground next to him. The workers’ rights activist group Treta no Trampo has recently been fighting for those working in Brazil’s gig economy, targeting low pay, dangerous working conditions, and contracts that leave those injured at work on the breadline. The tech might now be more advanced, but the fact that worker exploitation is as old as industry was brought home to me by Eugênio Sigaud’s 1944 painting Acidente de trabalho [Work Accident]. Included in the group show “A máquina do mundo” [The machine of the world], this social-realist canvas depicts a man sprawled on the ground of a building site, his fate equally unknown, as colleagues look down from the precarious scaffolding and ropes far above.

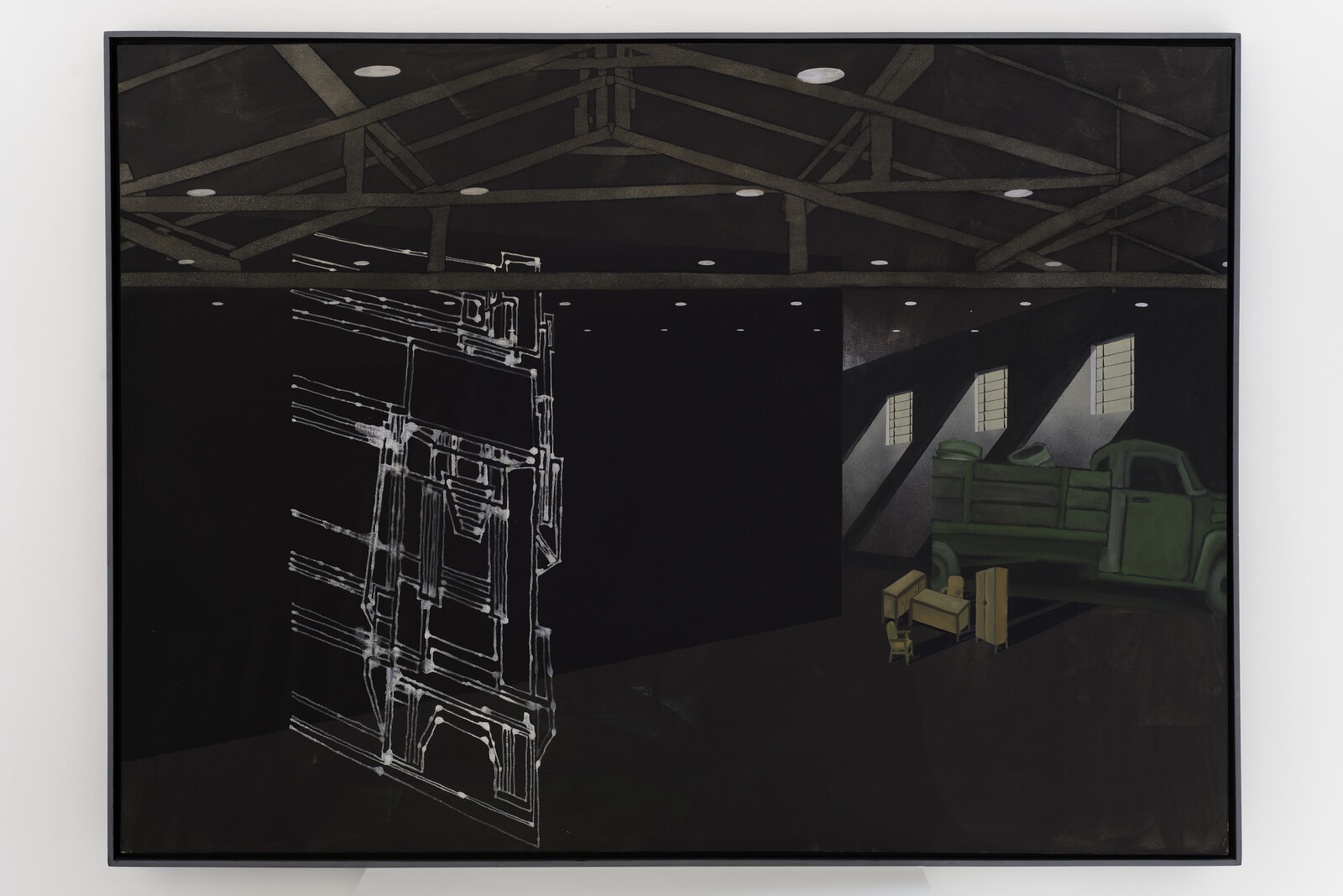

Sigaud’s painting is among the oldest squeezed into this 120-year survey of art dealing with Brazilian industrial history, which automatically drills into histories of economy, labor, human exploitation, and environmental extraction (some of these themes, perhaps inevitably given their size, feel underdeveloped). Works such as Frida Baranek’s freestanding, twisted ionized metal sculpture (untitled, 1988) and Alexandre da Cunha’s wall-mounted Portal (2016), a sheet of rusted material, formally point to Brazil’s industrial heartlands: the latter seems to be the waste product of the various geometric forms cut out of the metal’s flat surface.

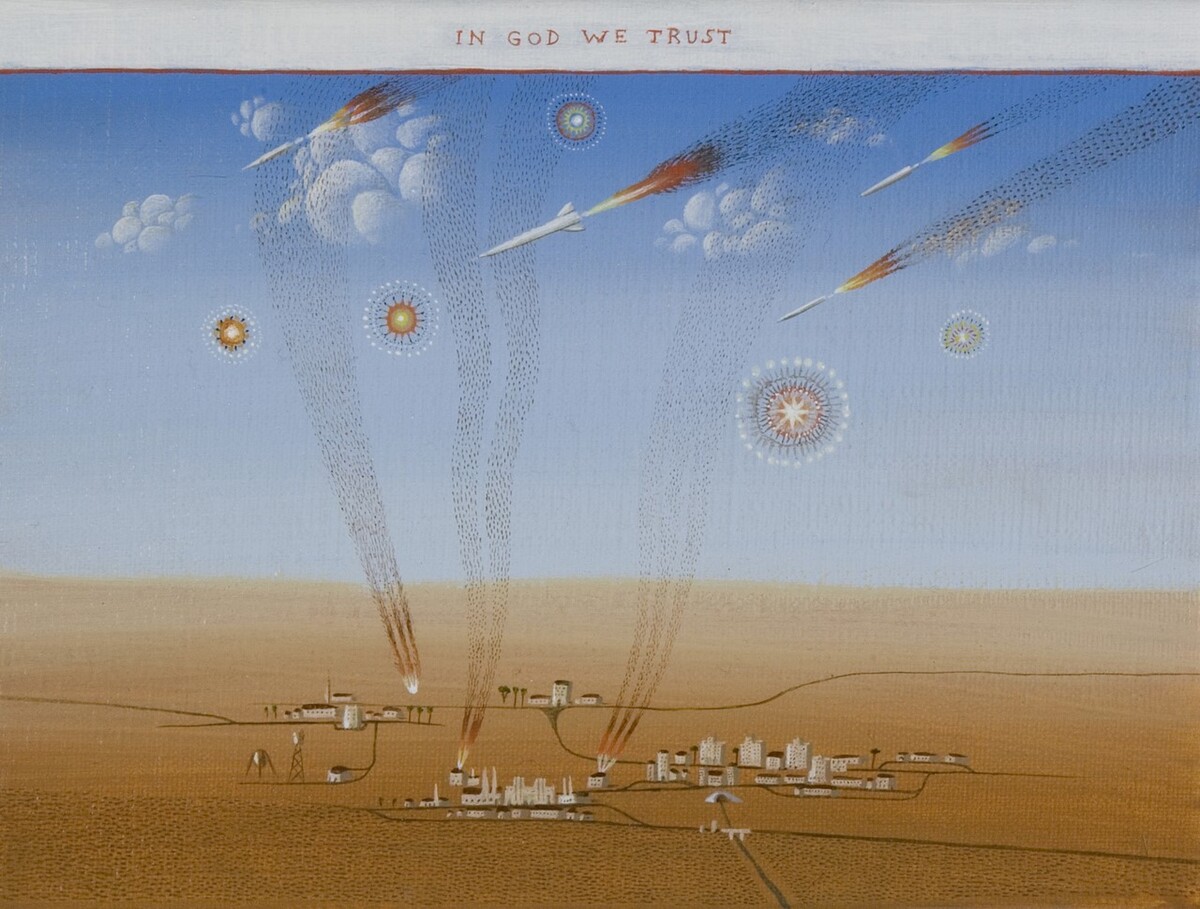

The consequences of industrial production are also invoked in paintings such as Djanira da Motta e Silva’s naïve composition from 1976, Mina de ferro, Itabira, MG, which depicts a shaft tower operating at an iron mine in the interior state of Minas Gerais. In Alcides Pereira dos Santos’s canvas Um mal que aflige (An Evil that Afflicts, 1992), a chimney belches smoke across a river; the image becomes only more depressing when one remembers that illegal mining in the Amazon region is at an all-time high. Mabe Bethônico’s series of newspaper collages Speaking of Mud (2019), in which the artist has removed the text so that only images of the mine-scarred Brazilian countryside remain, likewise speaks to several recent high-profile environmental tragedies born of corporate negligence. Yet many of Brazil’s most progressive tendencies were forged in its most polluting industries. This tension is never resolved in the exhibition and, arguably, in Brazilian society at large. How do the rights of the poorest in emerging or mid-tier economies square with the urgent environmental agenda? This dilemma goes some way to explaining the flourishing of political populism in the country over recent years.

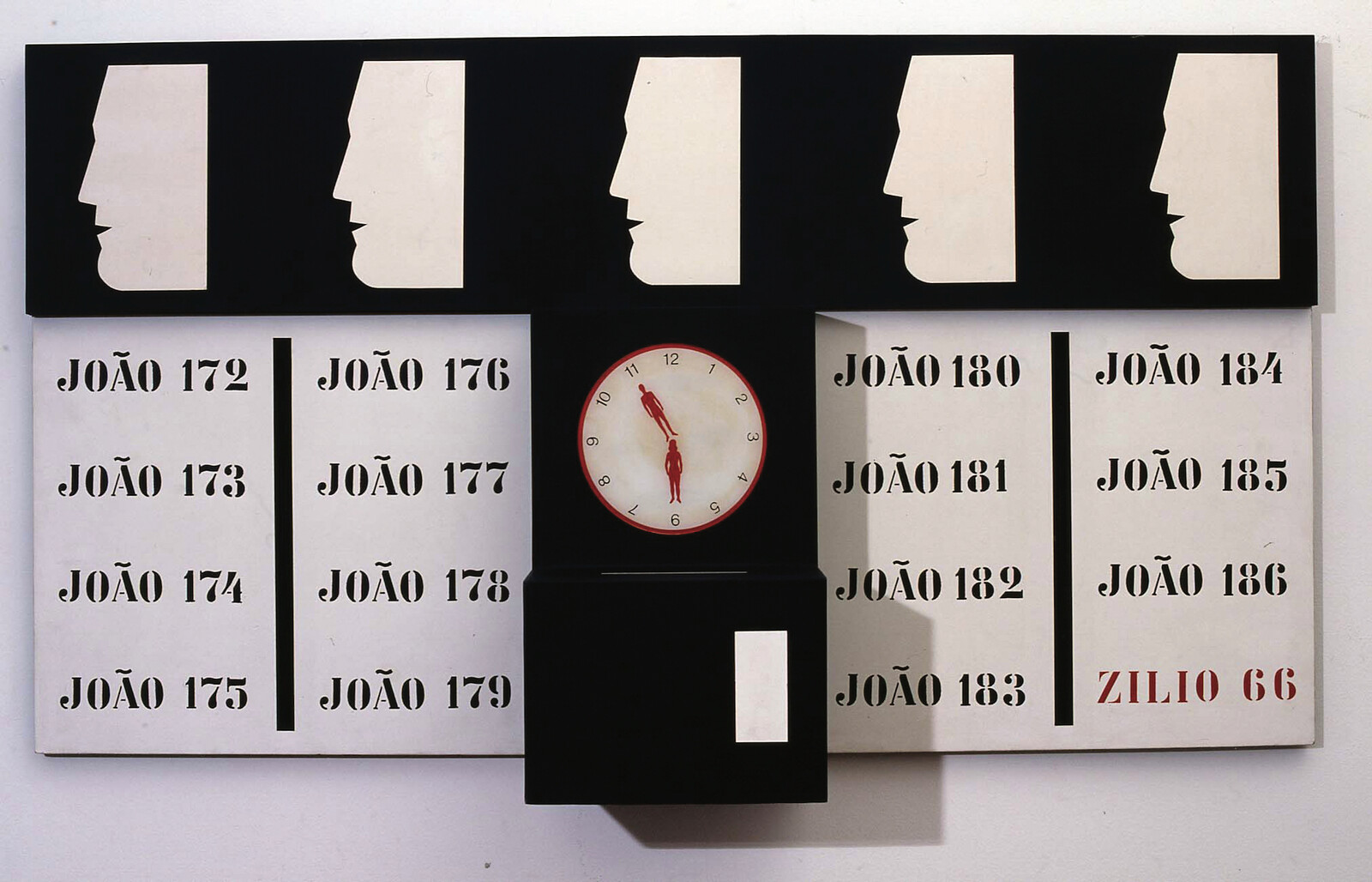

Bené Fonteles’s polemical photocopy collage works acknowledge this bind. O dedo do metalúrgico (The Metallurgist’s Finger, 1980) features the former president Lula—currently the most likely person to defeat Jair Bolsonaro in next year’s election—addressing a huge crowd outside the metalworkers’ union in which he forged his political career (the digit of the title refers to the one Lula lost aged 19 in a factory accident). He went on to found the left-wing progressive Workers’ Party (PT) in 1980; the rights of the poor and low-paid were central to his manifesto and pivotal to PT’s electoral success. Two further works by da Motta e Silva—her assured flat brushwork is an exhibition highlight—show coal and lime miners at work; her subjects’ body language and demeanor convey pride in their work.

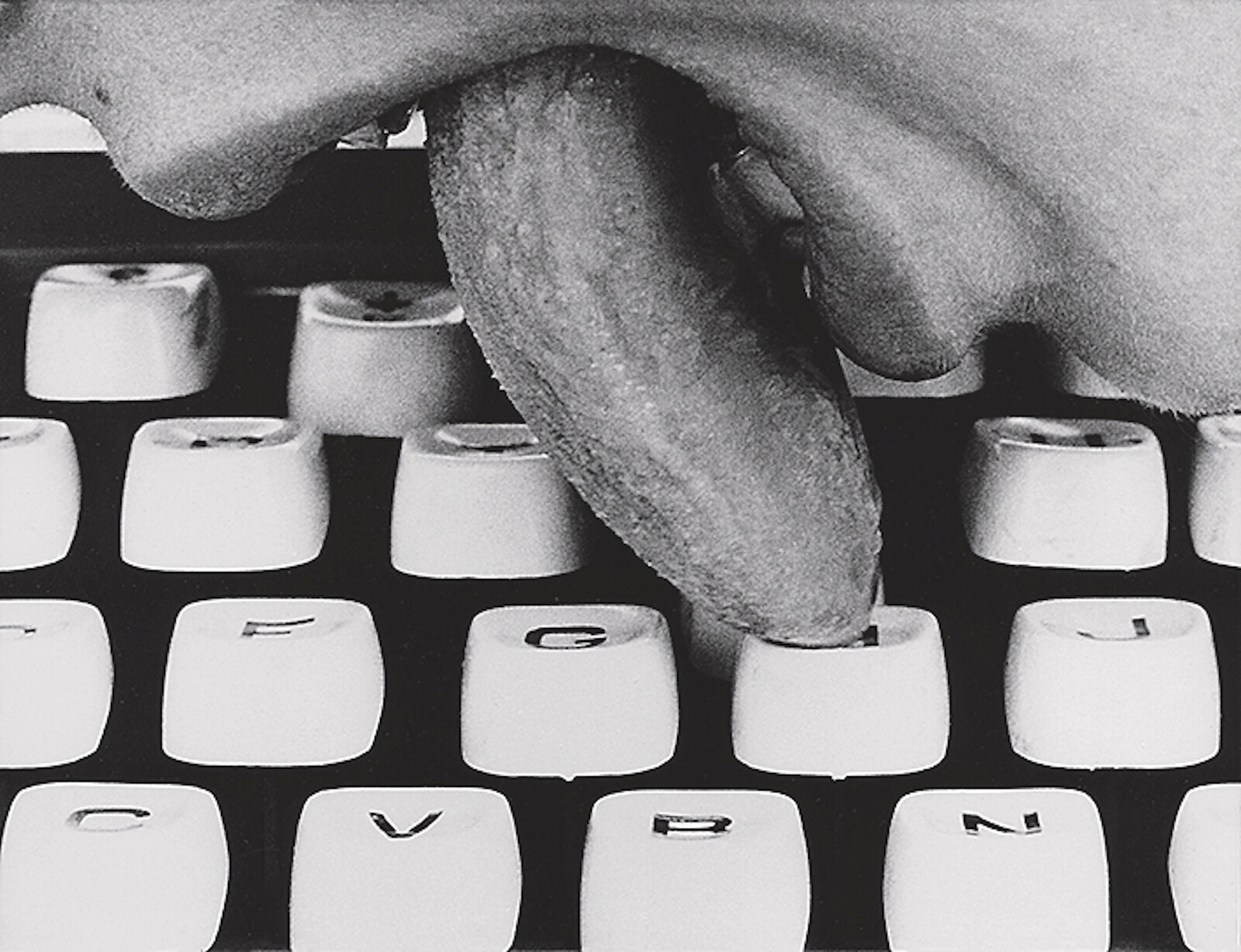

The frictionless wheels of today’s economy are evoked in a number of kinetic works and neo-concretist geometric paintings. The moving cogs of Ana Linnemann’s complex yet essentially pointless machine, A Mesa Do Ateliê (2018), resonate with the abutting circles of Ivan Serpa, Waldemar Cordeiro, and Willys de Castro’s mid-twentieth-century modernist compositions. Looked at today, as neoliberalism and the technological estrangement of the gig economy erode the dignity and safety of workers here and abroad, the curatorial context gives these artworks a sense of restless alienation. “A máquina do mundo” offers a reminder that the fight for workers’ rights is never over and must constantly adapt to new forms of capitalism. Today, the machine of the world is hidden behind a screen; the mechanics of exploitation remain the same.