The Rearview series addresses blind spots in recent art history by returning to an influential exhibition, artwork, or text from the past and reflecting on its relevance to the present. In this edition, Olivia Casa takes a new translation of Diamela Eltit’s Los vigilantes (1994) as an opportunity to highlight her pioneering artistic activism.

Diamela Eltit was a key member of the Escena de Avanzada, a group of Chilean artists and writers who denounced Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship in the aftermath of the 1973 US-backed coup that overthrew Salvador Allende. Varying in their approaches, they were united in their search for experimental strategies that would confront the regime’s policies and discourse—an aim epitomized by Colectivo Acciones de Arte (CADA), of which Eltit was a founding member.

The reissue of Eltit’s 1994 novel Los vigilantes, published in English as Custody of the Eyes, offers an opportunity to consider the relevance of the Escena de Avanzada to contemporary debates about art’s discursive strategies under repression.1 An epistolary novel narrated through a series of desperate letters dispatched by “Mama,” or Margarita, from a dystopian, authoritarian city, it leads us through a series of increasingly sinister events in which citizens are turned against one another and the unhoused are left to die on the streets. Our protagonist is watched over by her spying neighbors who report any infraction to the authorities, and monitored by the mother of her son’s father. Only when she is writing is she in control.

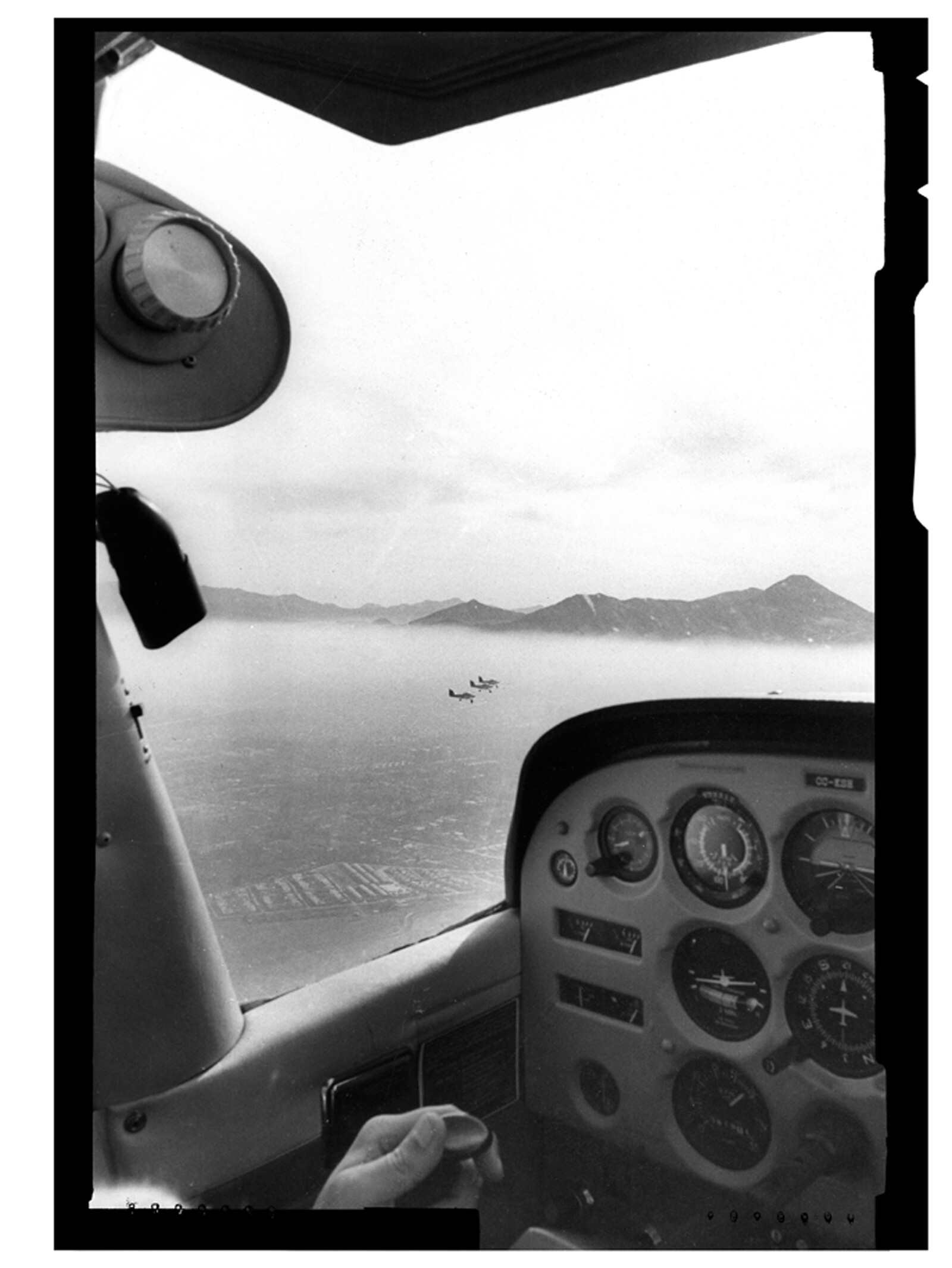

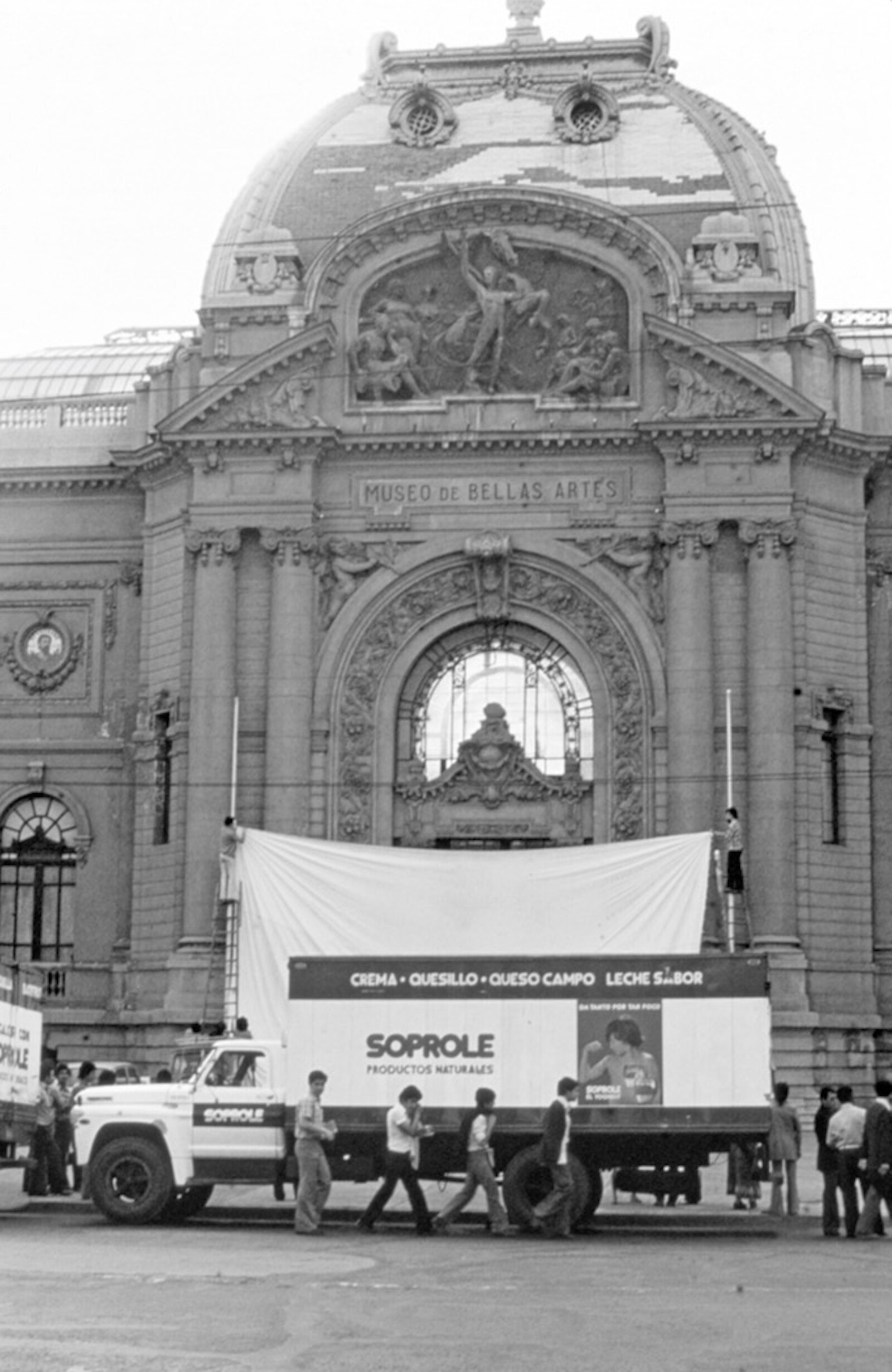

In common with Eltit’s other writing, performances, and collaborative art actions, Custody of the Eyes highlights the political significance of individual experience, witness, and memory in post-Pinochet Chile and political art more broadly. Active from 1979 to 1985, and comprising Fernando Balcells, Juan Castillo, Lotty Rosenfeld, and Raúl Zurita, alongside Eltit, CADA staged interventions into public space that appropriated and reconfigured symbols of the state (six airplanes in military formation, a procession of milk trucks, and the government-operated Museum of Fine Arts among them), deconstructing its discourse and criticizing its human rights abuses. For the group’s 1981 ¡Ay Sudamérica! they dropped 400,000 leaflets over Santiago from fighter jets; the pamplets’ text encouraged citizens to think of everyday experience as a form of art-making.

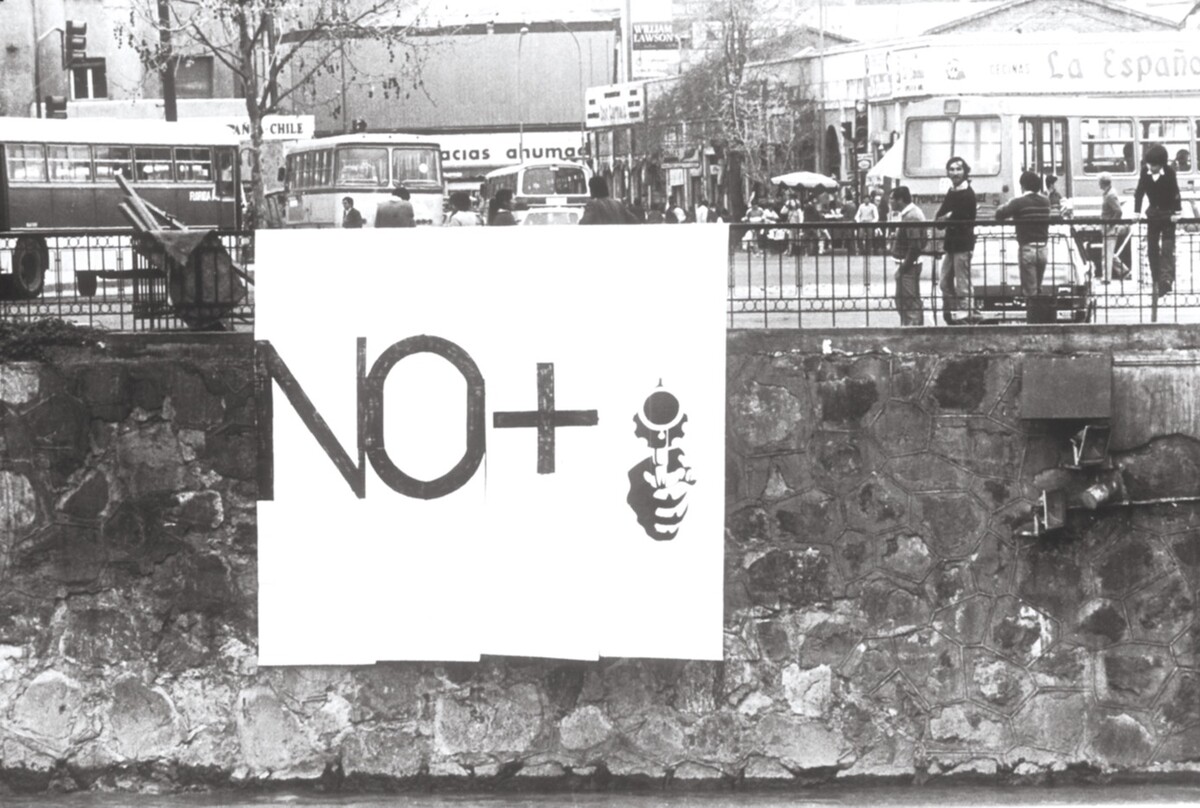

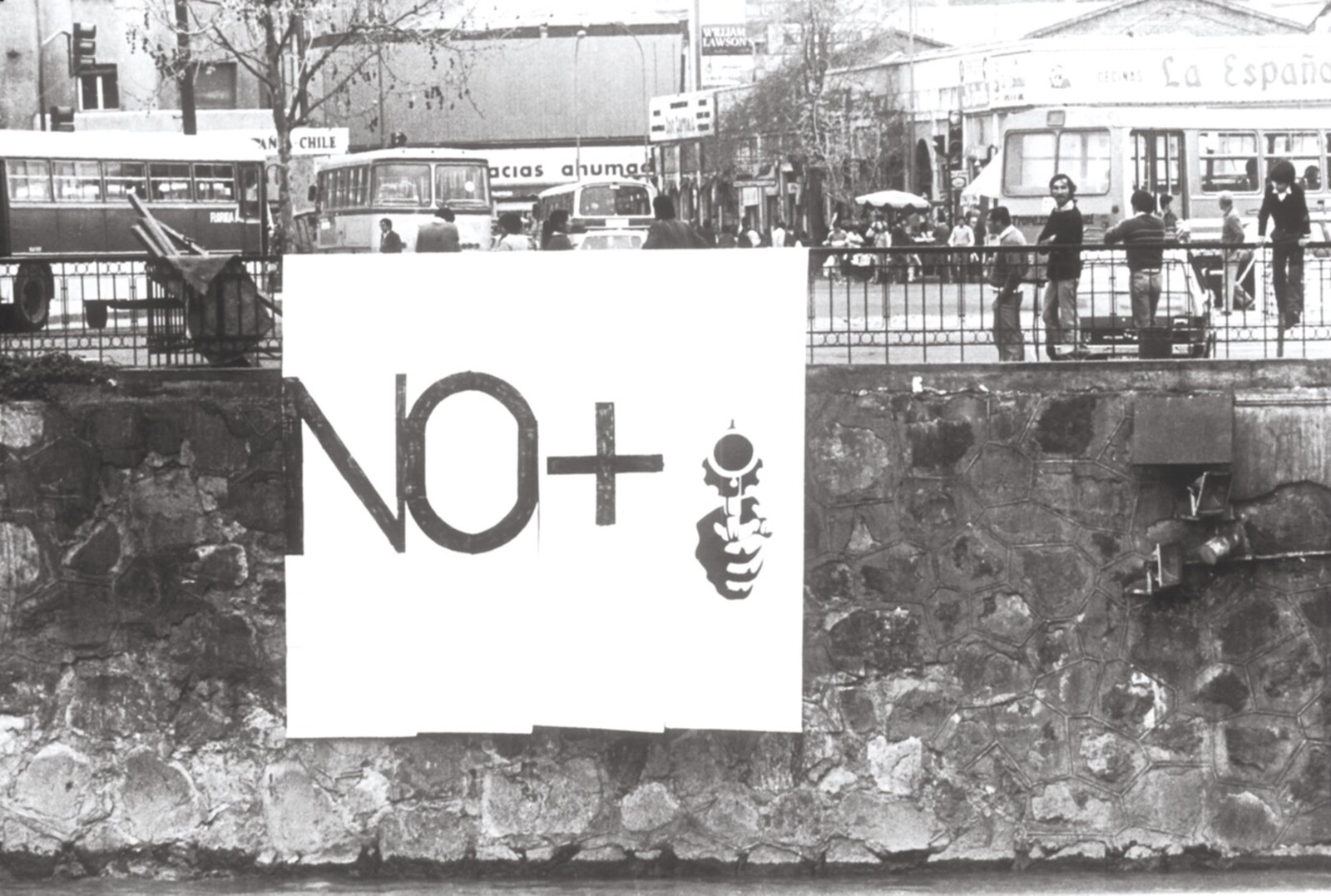

NO+ (1983), one of CADA’s best-known and widest-reaching actions, blended art and protest. The group wrote the word “NO” and the plus symbol—for “más” or “more”—on public walls across Santiago, including on a large-scale banner unfurled over the side of a bridge on the centrally located River Mapocho. The phrase soon appeared throughout the city and beyond: it’s still in circulation today, as artists and the public continue to reproduce the message in the streets, completing the fill-in-the-blank line of “No more” with a final noun. Such an action could just as easily be categorized as protest; in a 2008 review of a New York group show featuring the collective, Roberta Smith remarked, “it could be argued that some of CADA’s activities don’t need to be called art, that they constitute very effective agitprop meldings of idealism and activism.”2 Yet the gesture’s poeticism and radical open-endedness located it squarely within CADA’s critique of hegemonic structures. It transformed public space into a forum for anonymous and participatory forms of dissent.

Where CADA’s actions show us one response to political repression—based, as it were, in provocation—Eltit’s solo performances often made visible the relationship between the personal and the political, the body itself sometimes posing as a surrogate for the nation in crisis. In Maipú, from 1980, Eltit carried out a series of actions to this end. She cut and burned her arms and legs in a brothel, read excerpts from her then-unfinished novel Lumpérica (E. Luminata) that narrated her actions, and washed the building’s front steps. A comment on the physical violence of the dictatorship that drew attention to women’s unseen labor (maintenance and sex work), this action spun a byzantine web between private and public, individual and collective, text and performance. As Chilean critic Nelly Richard reflected in 1986, Eltit, like Raul Zúrita and Carlos Leppe, used “pain in order to recapture the communal body of suffering.”3

Such performances were incursions into public space; Eltit’s novels, by contrast, are insertions into the public record of national memory. Richard has written extensively on the role of forgetting in the post-Pinochet period, and in her 2018 essay collection Eruptions of Memory, she identifies, during the country’s transition to democracy after 1988, an official attempt to establish a break between the dictatorial past and democratic future: a discrete before and after. Richard calls instead for “dis-covering” the remains of the disappeared past, to “liberate diverse interpretations of history,” in considering how they inform the present.4 This process resonates with just about any nation grappling with collective trauma—not least in Chile, which is preparing to vote on a new constitution to replace the one written under Pinochet in 1980, amid the changing of the guard heralded by the election of the leftwing Gabriel Boric to the presidency late last year.

Eltit’s Custody of the Eyes presents a personal testimony that tugs at the loose threads of official discourse, Mama’s unreliable first-person narration exposing the fault lines of record-keeping. She describes the effects of authoritarianism on her body and psyche. We, the readers of her letters, occupy multiple positions at once. We are her witnesses, her adversarial addressee, the tribunal assessing the evidence in her case. We are implicated, even culpable, in this narrative structure, which presents the unraveling social fabric under authoritarianism, revealing witness and surveillance as two sides of the same coin.

Artistic responses to political repression often seek to uncover something unseen: it’s the strategies and subjects that change. We can trace a lineage of art responding to political oppression from CADA to more recent actions in contemporary Chile, during and after the country’s recent protest movements, such as the 2018 Feminist Tsunami and the Estallido Social of 2019 to ’21. Delight Lab is one example. The collective projects light installations consisting of a single word (hambre, dignidad, renace, humanidad) or a short phrase (Por un nuevo país, ¿Qué entiende ud. por democracia?) onto buildings to draw attention to social and political issues. LasTesis, from Valparaíso, circulates feminist theory in public space through large-scale choreographed dances. The viral “Un violador en tu camino,” or “A Rapist in Your Path,” draws from feminist philosopher Rita Segato’s writings on state-sanctioned violence against women and appropriates references to police tactics and slogans, in an indictment of abuse at the hands of government officials. Others still—Baila Capucha Baila, Liuska Astete Salazar, Alejandra Ugarte, Marla Freire Smith—have orchestrated performances that poetically condemn rights infringements faced by women, made even more dire during the global health crisis of the last two-plus years. Such projects foreground individual experience, but do so through public, participatory forms, engaging questions of collectivity that are likewise at the heart of Eltit’s work.

Art history loves categories, and it’s true that much of this work straddles the line between activism and art. To elude classifications was one of CADA’s goals, based as it was in rupturing the division between art and life, as the group wrote in 1982.5 Even when it was active, CADA was criticized for its actions alleged elitism, and today some of the collective’s work remains inscrutable at first glance. The duo Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis, formed in the late ’80s, rebelled against this perceived detachment by producing aggressively in-your-face performances that centered the disenfranchisement experienced by queer Chileans. Revisiting Custody of the Eyes reminds us of the potency of other responses to repression—witness, memory, testimony—that expose what Richard calls the “cultural residues” of the past and make personal experience visible. Sometimes writing is a no less courageous feat of dissent. There is power in the remaking of history, in recovering and uncovering the past.

Diamela Eltit’s Custody of the Eyes, translated from the Spanish by Helen Lane and Ronald Christ, was published by Sternberg Press in May.

Helen Lane and Ronald Christ’s new English translation of Los vigilantes was published this May by Stenberg Press. It coincides with Daniel Hahn’s new English translation of Eltit’s 2007 novel Jamás el fuego nunca, or Never Did the Fire, published by Charco Press earlier this year.

Roberta Smith, “When the Conceptual Was Political” in the New York Times (Feb 1, 2008): www.nytimes.com/2008/02/01/arts/design/01vida.html.

Nelly Richard, “Margins and Institutions: Art in Chile Since 1973,” published in Art & Text in 1986.

Nelly Richards, “Traces of Violence, Rhetoric of Consensus, and Subjective Dislocations” in Eruptions of Memory: The Critique of Memory in Chile, 1990–2015 (Cambridge: Polity, 2018).

CADA, “Una ponencia del C.A.D.A.” in Ruptura: Documento de arte. (Santiago: Ediciones C.A.D.A., 1982): icaa.mfah.org/s/en/item/732133#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-1026%2C0%2C3750%2C2199.