Pulling up to David Zwirner on the opening night of its tongue-twistingly-titled benefit show for Performance Space New York, the scene was chaotic: a several-hundred strong mix of fashion week, Armory week, and overdressed Chelsea partygoing crowds spilled out onto 19th Street, closed to car traffic and repurposed for a block party, complete with food stands and ice-cream truck. Inside, five long banners co-made by the exhibition’s all-star squad of artist-organizers—Ei Arakawa, Kerstin Brätsch, Nicole Eisenman, and Laura Owens—hung from a beam overhead.

These screen-printed, acrylic- and vinyl-painted Curtains (all works 2022 unless otherwise stated)—a title that evokes the fabric separating audience from proscenium stage—read like précis of each artist’s signature style: one shows a cartoonish Eisenman figure raising paint roller to wall, while Brätsch’s and Owens’s colorful, abstract geometries and pop-cultural influences infiltrate others. Two open, wooden structures on wheels evoked both stage props and domestic spaces (they are called “houses” on the gallery map). Behind the curtains, Performance Space’s metal rigging structure was temporarily relocated as décor, where it dynamically remodeled the gallery’s interior. A ramp leading to a platform wrapping around either side of the space served as the titular “mezzanine,” offering elevated views of the many paintings in the main room, hung in a row at neck-craning height.

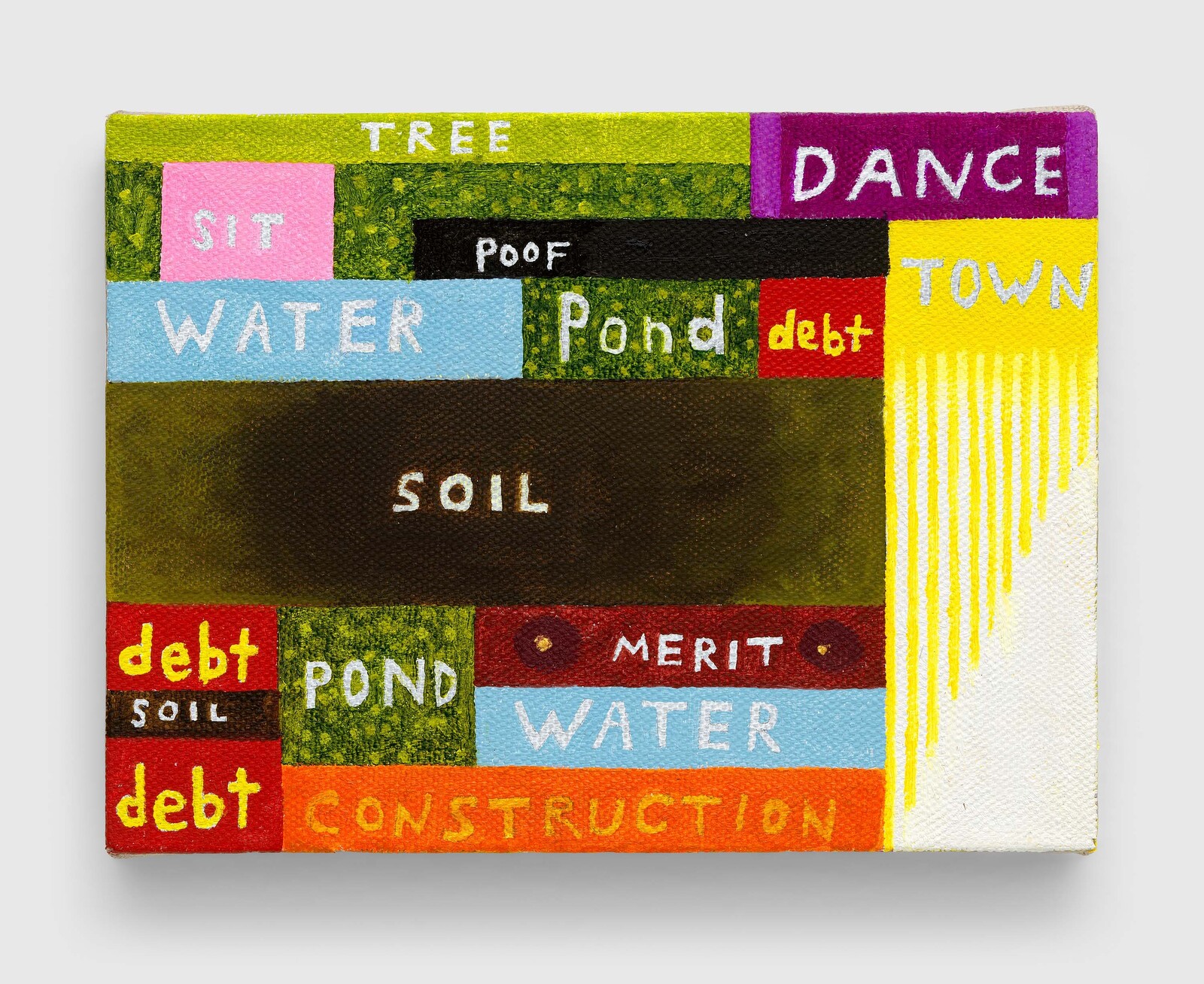

The procession of paintings featured a vast, if familiar, cast of characters (50 in all) spanning many of the trends that cluster dutifully at New York art fairs and in summer group shows: highly stylized, cartoonish, fantastical, and hypernaturalistic figurations; historical revisitations (Betty Tompkins after Caravaggio or Jutta Koether after Mondrian); abstraction, always; paintings that blur the line between figuration and abstraction; mixed-media, photographic, and digital deviations on painting (Wade Guyton and co.); chatty text-based paintings (Leidy Churchman’s Poof, featuring words like “Dance,” “Pond,” and “Debt” scrawled in bands of color); and some decadently garish paintings, including Katherine Bernhardt’s spray painted little piggy and Judith Bernstein’s dayglo Pink Gaslighting #4. The show ostensibly set out to present the playful (or “joyful,” as the press release states) interactions between painting and performance, and several works were performance-adjacent, in their titles if not always in their subjects or references. On Willa Nasatir’s Stage, a pink curtain parts to reveal a recumbent mechanomorphic figure—part (human? canine?) body, part shovel, part fan and other devices. Hadi Fallahpisheh’s Dancer in the Dark cheekily illustrated its title: the C-print shows a mouse, presumably our titular nocturnal dancer, fumes rising from its behind, in a composition framed by pastoral floral patterning.

In the backroom, emphasis was on process. To indicate this, the space was stripped to expose structural beams; half-painted walls sported roller marks and graffiti, while a series of small panels framed in blue painter’s tape lined the floor as if waiting to be hung. Openings cut out of the wall displayed some of Pope.L’s 400 “faux” lemons as part of the work BITTE(r), which is dispersed throughout the space; a set of email printouts detailed Rochelle Feinstein’s attempt to hire a commercial painter in China to make copies of her works below their respective paintings (Verbatim Hoc Moda/The Abramovic Method, 2013–15). Improvised brush marks graced the floor, and below our feet, encased under glass, were supplies: trays, rollers, flat brushes, foam brushes, cans of paint, rags, mixing palettes, and more. At the gallery’s entrance Nemesis Painting, co-authored by the four organizers, had warned us with its message: “Hardcore in the studio.”

The proliferation of surfaces and supports made it difficult, on first viewing, to focus attention on any single work. It’s possible the show started from too loose a premise. Or maybe it was just loose enough. Of course, the sympathetic nesting of nonprofit institution within the commercial circuitry of the gallery, the art fair, etc., isn’t new. But beyond the well-established rule that nonprofit philanthropy and (blue chip) art-world money go hand in hand, interdisciplinary programming, too, often confirms the ways in which the most commodifiable art form, painting, is regularly employed to prop up other practices—be they performative, discursive, or otherwise. Those are a harder sell. I want to see that “joy” in the way painting mobilizes the performative, and vice versa, in their promiscuous and unruly interplays, but in an exhibition so wantonly lacking performers, I couldn’t help but wonder: What does performance really have to do with it?

Or maybe the better question to ask is: What does performance do for painting? It wasn’t long ago that painting was described as being “beside itself.”1 If painting was once (long ago, perhaps) touted as an indexical, even performative, medium registering the artist’s gestures of inscription upon the canvas, it now seems as though performance, in such interdisciplinary contexts, has become the guarantor of painting’s often ambivalent claims over authorial presence. Conversely, painting can be said to suture many other social and economic dynamics and interactions as it moves through various frames of value and reference (say, the studio, the gallery, the museum, the publication, social media), accruing capital and audiences as it goes. But this kind of circulation is, paradoxically, not as easily afforded to performance (that ephemeral medium), which is by no means immaterial, requiring human and financial resources to cover artist fees, travel, rehearsals, production costs, décor, documentation, publicity, and more.

For those who were curious, the exhibition’s organizers were among nine painters to wax on the topic in a pre-recorded PSA delivered by four AI voices (“three good painters and one bad non-painter”). In this roundtable based on past interviews, the painters personified painting as a “nemesis” (cf: Eisenman’s 2014 midcareer retrospective “Dear Nemesis”), with whom they are each engaged in mortal combat. “Everything you’ve already done becomes a nemesis,” someone said. A good dose of healthy agonism. The goal, they articulated, is for painting to point not beside but rather beyond itself: to effect a passage from painting to image in an instant, to produce a “third term.” Painting can act. And while this nemesis, they conceded, “has to do with the market,” my question remained: Where does performance come into it? “In our world,” they answered, “painting itself is the performer, not the artist.”

The opening’s final act, then, was fitting. After recruiting 12 new non-performers (and presumably, non-painters) to his cabal—a difficult task given the audience’s reluctance to “participate”—Arakawa had them huddle for a few minutes of strategic planning before they dispersed into the audience to enact mock painterly gestures with brushes of all kinds (even invisible!) in hand. When their activities had subsided, the group migrated to the front of the gallery, where—enthralled by a dramatic live violin recital executed with the trenchant, muted staccato of Bernhard Herrmann’s score to Psycho (1960)—the newly formed troupe raised Brätsch above their shoulders and crowd-surfed her through a slotted canvas concealing an opening in the wall behind it. After many other volunteers, David Zwirner himself, before a fleet of iPhones raised to capture the spectacle, was eaten by the painting. There was something joyful about imagining that painting, announcing yet another “degree zero” of the medium, had been reborn this time as “performer,” only to absorb us all.

This review was amended on September 26 to reflect the fact that the talk delivered the words of nine painters (rather than only the co-organizers’, as originally stated) through four AI voices, and to correct the attribution of Nemesis Painting.

David Joselit, “Painting Beside Itself,” October, 130 (Fall 2009): 125-34.