In 2015, the disabled American writer Kenny Fries gave a reading as part of the program for “Homosexuality_ies,” an exhibition jointly sponsored by the Deutsches Historisches Museum and the Schwules Museum. During it, he posed a question: Where, he asked, was disability in this wide-ranging exhibit? Why had access for disabled people been ignored? The response to that challenge is “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer” at the Schwules Museum. Co-curated by Fries, Birgit Bosold, and Kate Brehme, it is one of the first international exhibitions to explore the artistic, political, and historical links between queerness and disability. It presents disability as sexy, provocative, tough, and a source of artistic strength—not a black hole of suffering and blankness.

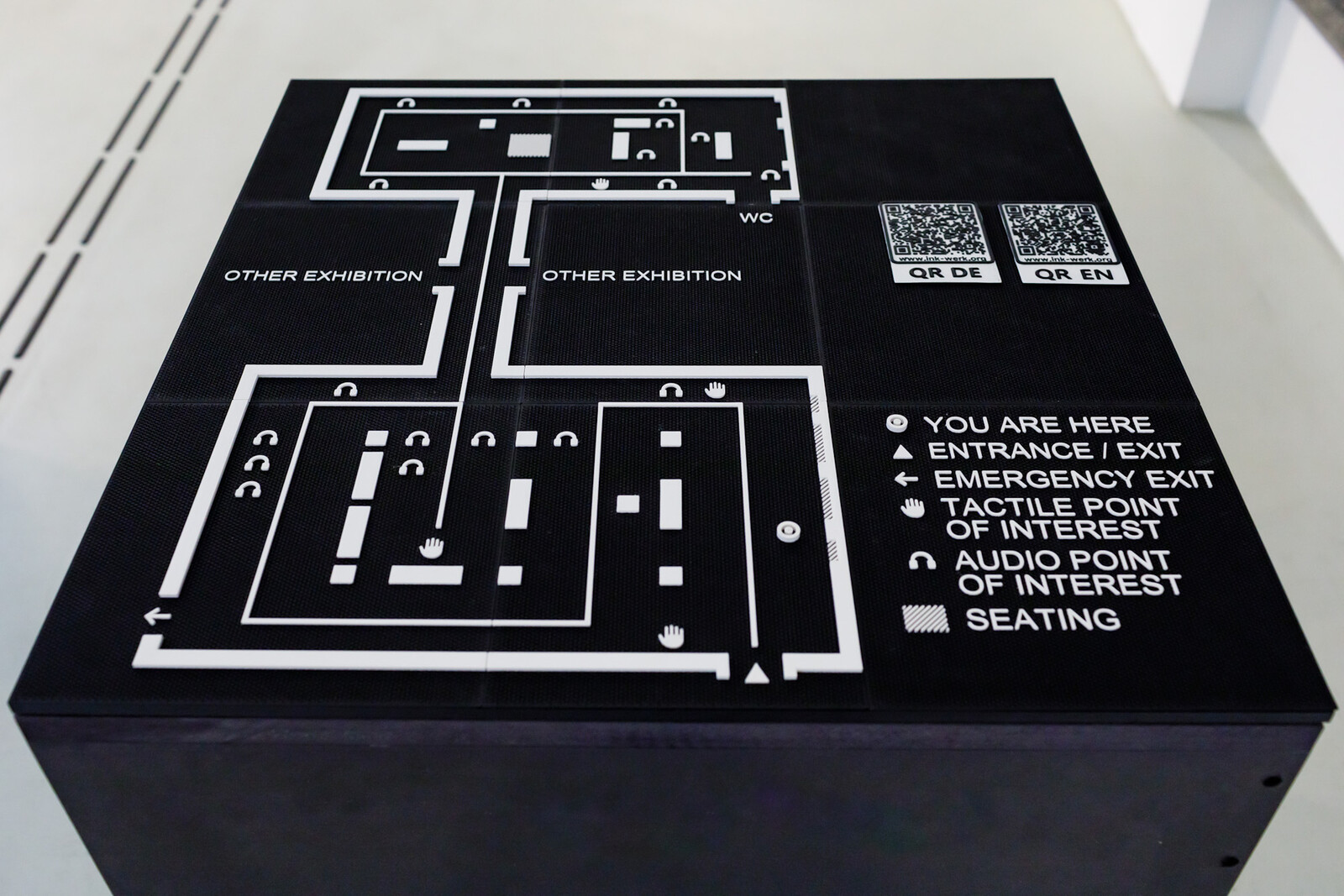

Access is at the heart of the show. Seated in my wheelchair, I could actually experience the art. Nearly always when I enter a museum (sometimes after having been assured that a show is “completely accessible”) I am able to see only a fraction of what is on display, and I am left wondering: “What does that wall text, too high for me to read, say?” I might be able see diaries, letters, magazines in a display case, but the height at which they are shown will make it impossible for me to read them. For those who are blind or deaf, museums can be even more exclusionary. It is a unique experience, therefore, to enter a museum exhibition such as “Queering the Crip” in which one’s presence is not an afterthought, but folded into the very design of what is presented.

The show opens with a replica of the Venus de Milo (ca. 150 BCE). The wall text quotes disability studies scholar Lennard Davis, who points out what is obvious—but almost always ignored: this statue, “considered to be one of the most beautiful female figures in the world,” has both arms missing and her marble flesh is covered with scars. The wall text goes on to explore the contradiction: we are shown an ideal body which at the same time has become disabled. Davis is one of the few scholars who have looked at the statue as it is, rather than seeing it in a state of imaginary “wholeness.” Next to it is a smaller replica of the statue which can be picked up and touched for those who need to access the work non-visually. It also suggests, although not explicitly, a queering of the experience of visiting a museum: a visitor can fondle a statue, interact with it in a sensuous manner, without the distance that vision requires.

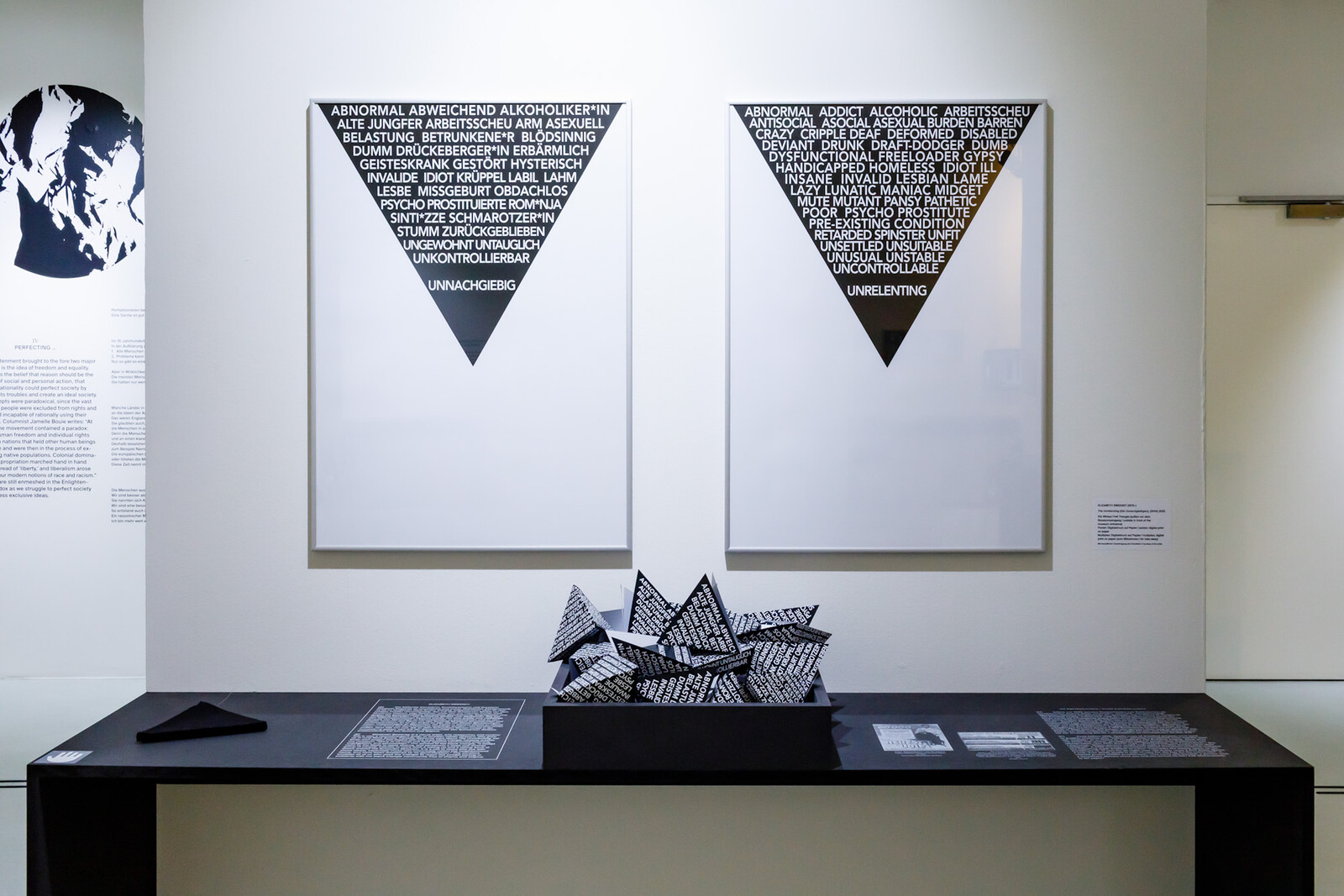

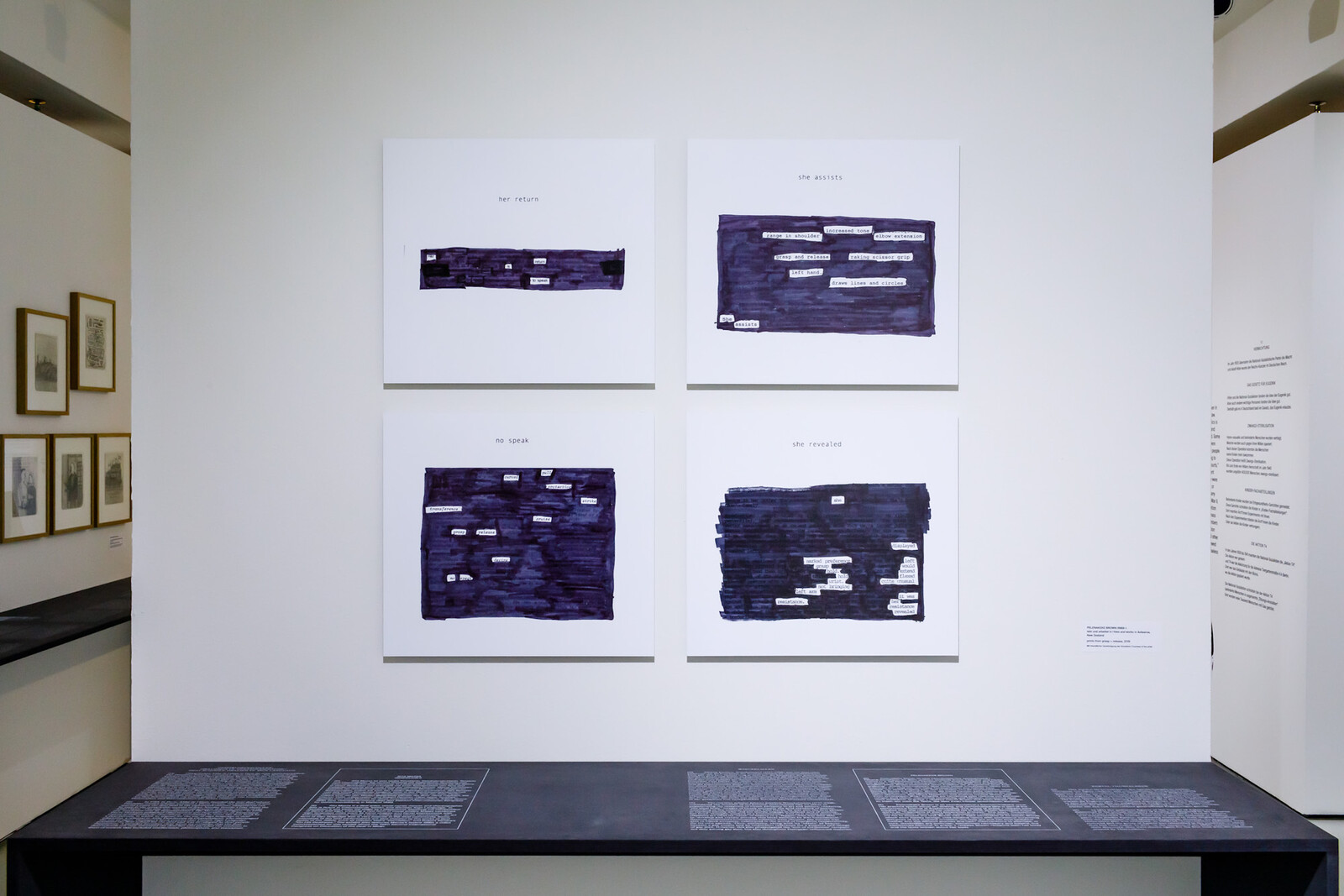

The historic background of western culture—which ranges from ancient Greece to pre-modern Europe, the Enlightenment, the eugenic policies of Nazi Germany, and contemporary articulations of disability justice—helps to contextualize a wealth of painting, film, and video documentation of dance. Among the most moving of these is the work of the multidisciplinary Samoan/Pākehā artist Pelenakeke Brown. Her piece grasp + release (2019) takes ownership of words from her medical files: in a sea of redacted black, the words “extend,” “quite unusual,” “marked preference,” and “resistance” take on a reclaimed meaning. Her spellbinding 2022 performance enter//return at Berlin’s Sophiensaele—part of a series of performances presented in conjunction with the exhibition—plays with how the words “enter” and “return” from the computer keyboard link to indigenous understandings of space and time.

Another standout artist is Mel Baggs, who described hirself as genderless and neurodivergent. In hir 2007 video In My Language, presented on a video display screen, Baggs shows hirself engaging in repetitive actions, such as stroking a computer keyboard, swatting at a metal chain with one hand while twirling it with the other, and moving hir hand through a stream of water coming from a faucet. In a section of the video called “A Translation,” a computer-generated voice speaks: “The previous part of this video was in my native language.” Baggs goes on to undercut the assumption that hir language must symbolize something; that through interpretation it can be transformed into “normal” language: “The water doesn’t symbolize anything.” In this, it reminds me of lines from the 1973 poem “Diving Into the Wreck” by another queer disabled writer, Adrienne Rich: “the thing I came for: / the wreck and not the story of the wreck / the thing itself and not the myth.”1 Baggs centers disability without translating it for a presumptively able audience, demanding that the viewer enter into hir experience.

A tactile floor guides viewers through the two open rooms of the exhibit. In addition to a number of dance and performance pieces on video screens, there are paintings by Riva Lehrer and photographs by Joey Solomon, as well as a tribute to icons of queer disability culture, Lorenza Böttner, Raimund Hoghe, and Audre Lorde. The exhibit culminates with an area that explores the principles of disability justice, which insists that disabled people can never be free in a racist, capitalist society. The last piece in the exhibit is Ancestors, Can You Read Us? (Dispatches from the Future), a multi-channel 2019 video by Syrus Marcus Ware which imagines people in the future speaking to us as their ancestors, envisioning a future “beyond the current epoch of Black social death.”

US disability studies scholar Carrie Sandahl, who coined the phrase used for the show’s title, wrote that sexual minorities and people with disabilities “share a history of injustice.”2 She might have added that both groups have managed to carve out rich and often joyful cultures in the face of oppression—as evidenced in this groundbreaking exhibition. A perhaps inevitable consequence of the show’s breadth is a lack of nuance in some of the historical material. Yes, ancient Greece created images of ideal bodies, but Hephaestus, one of the gods who looked down on humanity from Mt. Olympus, was lame. The gods were usually portrayed as embodying perfection—they were, after all, divine—and the notion that we should all be beautiful and healthy with the help of Botox, rigorous gym routines, liposuction, and superfood smoothies is of recent historical vintage.

One wall text discusses disabled people being forced to beg in medieval times. While this was surely sometimes a reality, begging was not the only role open to them—especially during periods of labor shortages—and many disabled people must have been integrated into daily life, since the rhythms of agricultural production meant that people did not have to fit into the rigid pace of factory production. The past this and other wall texts tells is Eurocentric, and one hopes this trailblazing exhibition will be the start of a deeper exploration of how queerness and disability have intersected in cultures across the world.

Adrienne Rich’s “Diving Into the Wreck” is available to read online at poets.org: https://poets.org/poem/diving-wreck.

Carrie Sandahl, “Queering the Crip or Cripping the Queer?: Intersections of Queer and Crip Identities in Solo Autobiographical Performance,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, volume 9, number 1-2 (2003): 25-56. Available to read online: https://www.ces.uc.pt/projectos/intimidade/media/Queering%20the%20crip_sandahl.pdf.