Friday in the Kali Yuga: Clement Greenberg and Bertolt Brecht

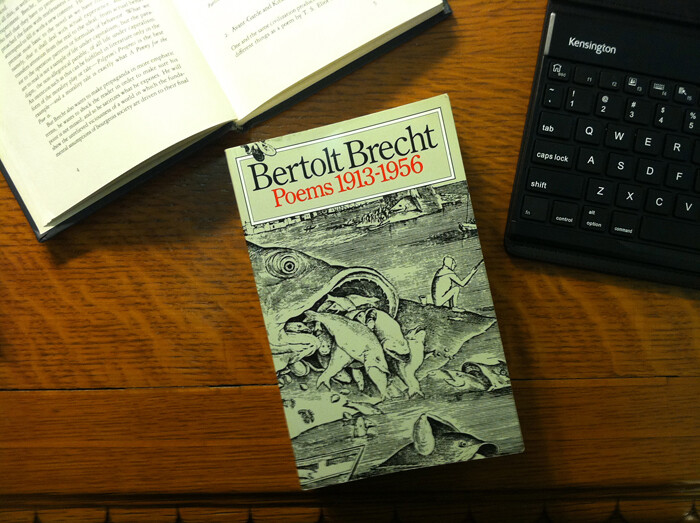

There’s a strong whiff of Abrahamic eschatology around all the web-geekery and folkloric appeal of Friday December 21, 2012. A single day of reckoning to put in your iCal, when the Messiah shows his cards. But like a ramped-up lottery pushing past the half-billion mark, this holiday fantasy cannot go on forever. Eventually the jackpot drops to zero because someone else has a winning ticket, or in the case of the day of reckoning and ultimate radical transformation: nothing happens, and see you all at work on Monday. Specific eschatological dates are harder to pin down in Indian and East Asian religions, where time’s ending is rather an endpoint in a cycle in symmetry with surrounding cycles, like the Hindu “age of the demon,” or Kali Yuga, with some 430,000 years of degradation, strife, and lust before the next cycle of ages recommences. In terms of kitsch signification, one could say that this conception of time is terribly complacent, where the dream of a better tomorrow becomes a simmering stew on low flame, a continuous browbeating and oppression that never finds relief in the flashiness of a revolutionary powder keg. On the other hand, time cycles have a certain resonance in relation to dialectics, containing contradictions and ambiguities that are constantly in play, like the Long March of 1934 in China, both a military defeat and political victory for Mao and the Communists.

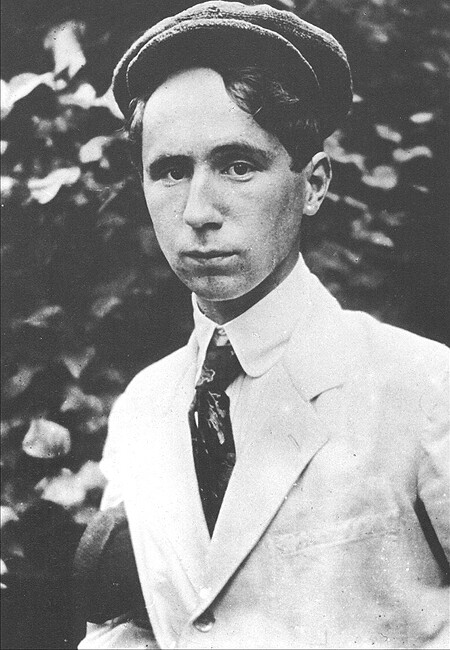

A similar inversion of positions, refraction of art history by rote, is to be found in re-encountering Clement Greenberg’s ideas of modernism through his literary criticism, especially when it coincides with rediscovering Bertolt Brecht the poet, an oft-forgotten facet of this fossilized modernist icon of the cultural Left. To read Brecht’s poetry today is to encounter the immediacy of a poetic attitude and language-play that is at once critical and hilarious, located in a dimension beyond tidy definitions of distanciation, alienation, reflexivity, and epic theater that encrust undergrad liberal arts courses. Even more timely is to see Greenberg sketch-out Brecht’s “serious parody,” describing the birth of irony in the modernist vanguard as a conscientious political decision, and the poet’s agile ransacking and two-faced deployment of popular forms. It’s an invigorating shot in the arm after the over-assigned readings of Greenberg’s “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939), which feels a bit off-kilter in terms of its neat divisions of high and low culture, strangely transpiring as promoting modernist abstraction as pure art for the elite, when the author might have been more concerned with countering the cultural mechanics of the Nazis, Stalinists, and Italian Fascisti. Now put the two together: try to imagine Clement and Bertolt sitting together shirtless in Central Park’s Sheep Meadow on bright summer afternoon in 2012: “In July I have an affair with the sky, I call him Little Boy Blue, glorious, violet, he loves me. It’s male love” (3rd Psalm, Brecht’s Hauspostille). Now try to visualize all the dead and dull appropriation of quotidian forms (the luxury objects of contemporary art) you’ve encountered in the past year as a kind of simultaneous ending and beginning, and gird yourself for a long-ass march into the future’s coming end that already started yesterday.

—Antek Walczak

Clement Greenberg’s “Bertolt Brecht’s Poetry”

There is a kind of modern poetry that gets its character from a flavoring of folk or popular culture. You will find it in the work of such poets as Apollinaire, Lorca, Mayakovsky and Cummings. Rimbaud and Laforgue are its original ancestors, as of so much else in modern poetry. It is anti-literary and anti-rhetorical. It takes over the attitudes and manners of folk and popular poetry for their tang, sincerity, irreverence and lack of pretention, as against the formality and overstatement of “book” literature, as against the endowed, the established, the respectable, in other words, as against Literature itself. This modernist poetry is racy and exuberant in backward countries like Spain and Russia, where folk culture still survives side by side with the formal culture of the city. In France, England and in this country it becomes wistful and impudent, and keeps to a minor key. It always has humor and sometimes, as in the case of Lorca, a justifiable quaintness, both of which are created by the transposition of the naive and lowbrow into sophisticated and highly self-conscious modes.

As much as Germany participated in “modern” movements, it never produced a poetry of this sort. Whereas in this country, France and England on the one hand, and in Spain and Russia on the other, popular and folk culture are far enough away from highbrow international culture to have spice and contrast, in Germany folk poetry has so become part of the main literary stream through the work of Herder and the Romantics that it cannot be opposed to it. At the same time German popular literature, including kitsch, is also intimately associated with folk culture. For this reason until rather lately there was no sharp line to be drawn between highbrow and lowbrow in German poetry. Popular songs in Germany are not art, but neither are they half so shoddy as their French and American equivalents. (Compare the verse of such frankly popular German songs as Zwei Herzen in Dreivierteltakt and Jeden Sonntagabend das Dorfmusic Spielt with anything on the same order in English or French.) They still show the saving evidences of a recent folk ancestry.

The late development of German culture, which accounts for this, also accounts for the peculiar nature of German avant-garde movements, which were never so detached from and irresponsible towards official culture as in France and elsewhere. The fact is, that the Germans do not have enough classic literature, have not produced enough in the past to enable them to dispense with ambitious contemporary work. There is not, actually, enough to read, enough to counterpose to the present. (This is why the Germans translate so much.) So that no sooner did German avant-garde movements appear than they were reabsorbed by official tradition and by society as a whole, no matter how intransigent they may have tried to be. Rilke’s poems could sell 60,000 copies, and before Hitler, Germany was the best market for advanced painting. Stefan George and his circle, with all their contempt for the bourgeois herd, found themselves raised very early to the status of official prophets of the beautiful; and their fate was that of almost every avant-garde cénacle in Germany during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

When Bertolt Brecht found himself pulled in the direction of Rimbaud—the Rimbaud of Season in Hell—he had to start from scratch to devise a means of reflecting this influence. He could not learn from Apollinaire, nor from Expressionism or anything else in German. So he proceeded to do something quite original by developing a poetry of serious parody, compelled and helped by the peculiar nature of German literary tradition. Popular and folk poetry are but one ingredient of the advanced, experimental, international styles of Apollinaire, Lorca, Mayakovsky and the others.

In Brecht’s first phase the verse technique itself is more or less conventional, experiment being confined to an occasional variation of beat or a daring enjambment. It is hardly the kind of poetry we expect from one who as a playwright was under the influence of Expressionism, and whose fellow poets of the same generation were more or less dominated by it. What is new is not what we customarily associate with the new in modern poetry, but consists in the way in which Brecht exploits the past and popular accomplishments of German poetry for his own subversive and anti-literary irony.

Parody ordinarily finds its end in what it parodies, but in Brecht’s hands it became the means to something beyond itself, more profound and more important. The special quality of Brecht’s poetry—particularly until 1927 when his Hauspostille collection was published, shortly after which he first became a Communist sympathizer—arose from a disparity. He took a form like the German ballad, which is inextricably associated with the countryside and a semi-feudal way of life, and charged it with a new city content and feeling too powerful and morbid for the ballad convention to bear. This incongruity is the strength of the poetry, is a good part of it. Now, were one to do this in English the result would be comic and very little else, for there would be too great a disparity to produce anything but humor. The English ballad is literary archaeology, and it is as archaeology that it appears in Coleridge, Keats, Rossetti and Morris, who escape the ridiculous only because—wisely and romantically—they fit it with an appropriate historical content. But the German ballad was in a sense still alive as late as Heine and Morike; its originals had not yet completely disappeared from the German countryside. And today it is still almost a serious form, too recently dead to be quaint, still taken seriously by several contemporary German poets whose verse is much less stale than John Masefield’s. What is true of the ballad is more or less true of most of the other forms parodied by Brecht. The popular and traditional modes which Brecht uses are still strong enough to resist what Brecht wants to make them say in more ways than by producing humor. They still live respectably outside textbooks, and their associations are part of the life of almost every German. Brecht acclimatizes them, and Goethe and Luther as well, to shady neighborhoods. Thus the two poles of Brecht’s early poetry are not so much the naive or quaint as opposed to the sophisticated, as the dangerous and irreverent as opposed to the safe and the respectable, the slums and the gutter as opposed to the countryside and suburbs. The incongruities must in some measure proclaim themselves by humor, but it is not the humor of the ridiculous, but rather that of irony.

The stanza, meter and some turns of phrase, even the motif, of Brecht’s Legende vom Toten Soldat, or Legend of the Dead Soldier, might be those of an 18th century folk song still sung today in Germany by school-children. Many German ballads are about soldiers and death, and Brecht’s theme is really congruent to his form. But his content and feeling are utterly opposed to the content and feeling with which this form and this theme have generally been associated. A great deal of the poem’s force springs from this contradiction:

Und als der Krieg im fünften Lenz Keinen Ausblick auf Frieden bot Da zog der Soldat seine Konsequenz Und starb den Heldentod.

Der Krieg war aber noch nicht gar Drum tat es dem Kaiser leid Dass sein Soldat gestorben war: Es schien ihm noch vor der Zeit….

Und sie nahmen sogleich den Soldaten mit Die Nacht war blau and schön. Man konnte, wenn man keinen Helm aufhatte Die Sterne der Heimat sehn.

Sie schütteten ihm einen feurigen Schnaps In den verwesten Leib Und hangten zwei Schwestern in seinen Arm Und sein halb entblösstes Weib.

Und weil der Soldat nach Verwesung stinkt Drum hinkt ein Pfaffe voran Der über ihn ein Weihrauchfass schwingt Dass er nicht stinken kann.

Voran die Musik mit Tschindrara Spielt einen fIotten Marsch. Und der Soldat, so wie er’s gelernt Schmeisst seine Beine vom Arsch…. 1

The seeming crudeness of the meter, the dry, banal idiom and the economy of details are the setting against which the ballad projects its horror, intensified by the contrast. This is really parody in reverse, for what Brecht does is to raise the ballad form to a dignity it has not enjoyed for a long time, even in Germany. Nevertheless, it is parody. The humor, savage as it is, results largely from the contrast between the situation and the accumulated habitual responses provided by tradition—it is not simply that Brecht uses a certain formal pattern: he uses everything historically connected with that pattern—and what that situation and those responses develop into. The ballad style of understatement is over-extended and, in a way, criticized, by being forced to understate grotesque and ludicrous horror….

Brecht is a consummate parodist because he is above all a playwright and dramatic poet, and by instinct puts on a mask before speaking. He is a satiric poet, but down at bottom not a lyricist. He has to cast himself in a role before the poetry can come. All the poems, save for a few, in the Hauspostille, or Homilies for the Home, are parodies in some way or other. Everything is grist for Brecht’s mill: the Lutheran hymn, Bible versicles, the waltz song, nursery rhymes, magic spells, the prayer, even jazz songs—which last he succeeds in converting to his purpose only because colloquial German hasn’t the banality of its English counterpart and is much less remote from literary language—and at that, even the jazz song tends to become a ballad when Brecht uses it, especially in the handling of the refrain. Because most of these forms are closely connected with music and because Brecht himself is very much interested in music, he was able to collaborate with composers—something rare in modern poetry—and quite a few of his ballads have been set to music, in addition to the librettos he wrote for Kurt Weill and Hanns Eisler.

By parodying forms that are in circulation outside the customary channels of “book” literature, Brecht gained for his poetry a certain sharp contemporaneous quality such as we can hardly find elsewhere in modern verse. It seems to me that Auden learned much from him and found his example an aid in his endeavors to free modern English poetry from the straitjacket of pure poetry and to make it deal once more with wide ranges of experience. If poets can no longer deal with politics, religion and love on their own terms, and earnestly, because to take too positive a stand would involve them in unpoetic controversy, then they must deal with them ironically. The attribution of influences is dangerous, but I cannot help thinking that Auden learned something from Brecht in the way of working into poetry slang, the modish phrase, echoes of the rhetoric of the past, the scraps of intelligent conversation, the clichés of the intellect and of journalism, and the flat up-to-date wisdom of psychology and Marxist politics. Auden, too, parodies prayers, odes, magic spells and nursery rhymes. His precocious wit is his own, and it is something subtler and more cultured than Brecht’s, but he must have got more than a hint from him as to how to metabolize it into poetry….

As much as Brecht is a parodist and strives for an anonymous manner, there is a unified style in the Hauspostille poems which constantly breaks through with its personal resonance. His most consistent manner is one of dry understatement, simple, yet indirect, affectedly restrained. But what makes his style most characteristically his own are the shifts in tone and transpositions of key. To put established and well-worn conventions to new uses is to strike discords. Dry matter-of-factness unfurls unto Biblical grandiloquence. The sententious passage collapses abruptly at a banal expression or trivial image, or when the rhyme falls on an auxiliary verb or the main stress on the illogical word. The grim and horrible alternate with the idyllic, the brutal with the sentimental, the cynical with the falsely naive. There is a process of inflation and deflation, a succession of anti-climaxes:

lch, Bertolt Brecht, bin aus den schwarzen Wäldern. Meine Mutter trug mich in die Städte hinein Als ich in ihrem Leibe lag. Und die Kälte der Wälder Wird in mir bis zu meinem Absterben sein.

In der Asphaltstadt bin ich daheim. Von allem Anfang Versehen mit jedem Sterbsakrament: Mit Zeitungen. Und Tabak. Und Branntwein. Misstrauisch und faul und zufrieden am End.

Ich bin zu den Leuten freundlich, Ich setze Einen steifen Hut auf nach ihrem Brauch. Ich sage: es sind ganz besonders riechende Tiere Und ich sage: es macht nichts, ich bin es auch…

Gegen Morgen in der grauen Frühe pissen die Tannen Und ihr Ungeziefer, die Vögel, fängt an zu schrein. Um die Stunde trink ich mein Glas in der Stadt aus und schmeisse Den Tabakstummel weg und schlafe beunruhigt ein.

Wir sind gesessen ein leichtes Geschlechte In Häusern, die fur unzerstörbare galten (So haben wir gebaut die langen Gehäuse des Eilands Manhattan Und die dünnen Antennen, die das Atlantische Meer unterhalten.)

Von diesen Städten wird bleiben: der durch sie hindurchging, der Wind! Fröhlich machet das haus den Esser: er leert es. Wir wissen, dass wir Vorläufige sind Und nach uns wird kommen: nichts Nennenswertes.

Bei den Erdbeben, die kommen werden, werde ich hoffentlich Meine Virginia nicht ausgehen lassen durch Bitterkeit Ich, Bertolt Brecht, in die Asphaltstädte verschlagen Aus den schwarzen Wäldern in meiner Mutter in früher Zeit.2

This is from the poem Von Armen B. B., or About Poor B. B., in which Brecht pretends to speak for himself. The mannerisms of a variety of literary and non-literary attitudes, past and present, are juxtaposed with the flair, humor and seriousness which are Brecht’s genius. He dramatizes himself only in order to puncture every false attitude within reach, to exhibit the disparity between literature and the facts.

Brecht misfires occasionally, usually because of a lapse in taste. Sometimes the irony is over-labored, and the grotesque and macabre overdone. Sometimes the understatement is overstated. But at that, it is remarkable how rare Brecht’s failures are: there is hardly a really bad poem in the Hauspostille collection.

Brecht wanted to write “popular” because, like Rimbaud, his position was that of the pariah who has no patience with the formalities, either of living or of literature. In the Hauspostille and in the plays of the same period he does not storm against society; the lumpenproletariat, the gutter men, complain and lament, but they do not criticize. Brecht simply rejected civilization entire and went in for a nihilism of despair which permitted him only one value: comradeship, which he found at its purest where it had the least competition: the Bohemia of tramps, suspicious characters, freebooters and sailors. “Through thick and thin” and “true to the end” were bromides that Brecht took seriously. (One given to that sort of thing might find the Brecht of this period a perfect example of proto-Nazi temperament, with Führerprinzip, violence, freebootery, pimps and all.) He celebrates the example of women who out of faithfulness follow their men into degradation, who hang on to their partners through corruption and stench, humiliation and despair. In search of the places where the horror of civilization is most naked, he seeks out its horizontal as well as vertical frontiers. The traditional German wanderlust had become morbid. Brecht had grown up in a post-war Germany whose younger intellectuals were fascinated by low life, crime and perversity, and aficionados about the movie America of gangsters and the Wild West. There was a push downwards and outwards, away from the street levels of the asphalt wilderness. Wearing a Kipling costume, Brecht made overseas expeditions in verse to tropical hells, Mexico, the Wild West, nameless deserts, uncharted oceans. But it was Kipling in despair, a Kipling who had read Rimbaud, had nobody waiting for him at home, and was bored and sick to death.

Brecht was the poet-laureate of the Germany which had been dislocated by the Inflation, and which found in him a talent and a temperament to express its mood. He scandalized it and he fitted it. It was when all Germany had a consciousness of itself as a pariah among the nations; Brecht universalized and sublimated this consciousness by identifying it with all mankind. He was having plays produced, some of them with success; he had several notable theatre scandals to his credit; he was a very young man with a bright future, not half so isolated from society as he might have been; a good part of his audience agreed with what he said, as shocked as it was, and he did not need to be obscure in his poetry. It was this community of mood that gave his verse its carrying power, circulated it in alert society, and deprived his nihilism of pose and idiosyncrasy. The devaluation of money justified the devaluation of every other value. Mankind was exiled from its possessions, tangible and intangible, and every individual was an alien. In spite of his pessimism, it would be wrong to consider Brecht as a case of the lonely poet.

However, there is a side of Brecht which cannot be explained by post-war Germany, but is the result of his Lutheran upbringing and is part of the particular personality which he cannot help being. His attitudes have always had a religious color; and underneath his nihilism as well as his Communism there lurks a religious moralist. Brecht’s habitual bad temper and sour disposition are not solely the result of dissatisfied egotism; they also belong to one who finds nothing but horror and loathing for the acts of his time, and little or insufficient satisfaction in the constant, sensual pleasures. It is not merely to be sacrilegious or to take advantage of a convenient form that he parodies liturgical style so much. He means to have his tongue in his cheek when he says sin, but his tongue comes out; for Brecht, without believing in religious virtues or being a mystic, is conscious of sin the way a believer is. It fills him with an unaccountable horror and fascinates him, as it fascinated Baudelaire, because for himself it really has the quality of sin. He is never less a parodist than when he parodies Luther or the Old Testament, whether to curse life in general or only Hitler. It is the style of his temperament.

Until 1927 at least, Brecht rejected everything, Lenin as well as the Kaiser. He wrote a poem about the Red Army:

…In diesen Jahren fiel das Wort Freiheit Aus Mündern, drinnen Eis zerbrach. Und viele sah man mit Tigergebissen Ziehend der roten, unmenschlichen Fahne nach….

Und mit dem Leib, von Regen hart Und mit dem herz versehrt von Eis Und mit den blutbefleckten leeren Händen So kommen wir grinsend in euer Paradeis.3

Since Schiller and the Sturm and Drang there has been a tradition in Germany of the young poet as reckless rebel—who finally takes a responsible position towards society. Brecht has in his way followed this trite pattern. Becoming a Communist some time around 1927, he went through what might be called a change of personality. He was converted. He abandoned his passive irresponsibility for an attitude so utterly earnest that it is almost suspect. Turning didactic poet in the most literal sense, he saw beyond the ends of poetry as poetry the obligation to teach the ignorant and poor how to change the world.

It was as a result of his previous poetry rather than because he had set out to write with such an intention, that Brecht began to believe that it was possible to produce contemporary poetry and drama of a high order which would still be palatable to the masses. He devised a theory of a new anti-Aristotelean form of drama which he called the “epic” drama. Instead of involving the spectator emotionally, it would sober and cool him into an objectivity which would enable him to consider the dramatic action, not as one who identifies himself with the roles enacted on the stage, but from the point of view of his own practical, every-day interests as a member of society. The “epic” drama would teach above all. This theory is enunciated with such meticulous dogmatism that there hovers over it an air of that straight-faced clowning we are always forced to suspect in Brecht. It is as if he were parodying Aristotle and Marx at the same time. The then current Stalinist line on proletarian literature—very much an unknown quantity and the object of a haphazard search—gave free play to Brecht’s theories, while both his originality and his dogmatism were encouraged by the exaggerated aggressiveness at the time of the Third International’s political line. As he quoted the right authorities and repeated the correct shibboleths, he received more or less official support from the German Communist Party.

Brecht’s first stage as a poet culminates in the magnificent libretto of the Dreigroschenoper, which was still written in what I choose to call his Hauspostille manner, and still somewhat “Aristotelean,” although Brecht had already made his turn to Communism. After this his style underwent a radical change. In the choruses and recitatives interspersed through the “epic” Lehrstücken, or “didactic pieces,” he began to use an unrhymed free verse designed to accord better with the rhythms of contemporary speech and to cut away those non-essential embellishments of poetry which might dissimulate the austerity of the Bolshevik method. In the directions accompanying the printed texts of the didactic pieces Brecht emphasized the necessity of a “dry” delivery. Poetry was to become stripped, bare, prosaic. It was to be settled with large colonies of prose. (I do not want to exaggerate Auden’s debt to Brecht, but again it seems to me that he got hints here as to how to assimilate prose phrasing to poetry.) Rhythm was no longer to be metric or musical, but forensic, persuasive and rhetorical. A fair specimen of Brecht’s new style is the Lob der Partei, or Praise of the Party, from the play Die Massnahme:

Der Einzelne hat zwei Augen Die Partei hat tausend Augen. Die Partei sieht sieben Staaten Der Einzelne sieht eine Stadt. Der Einzelne hat seine Stunde Aber die Partei hat viele Stunden. Der Einzelne kann vernichtet werden Aber die Partei kann nicht vernichtet werden Denn sie ist der Vortrupp der Massen Und Fürht ihren Kampf Mit den Methoden der Klassiker, welche geschöpft sind Aus der Kenntnis der Wirklichkeit.4]

Brecht had become so inveterate a parodist that he could not prevent himself from parodying even the Bible in his political poetry—although there may be the influence of Stalin’s painfully simplified, catechism style of oratory. However, more than parody is involved. The same protestantism that Brecht showed when he was a cynic manifested itself in his adherence to Marxism. Lenin’s precepts became for him an eternal standard of conduct, and Bolshevism a way of life and a habit of virtue rather than a historically determined line of action intended to realize a definite goal. The didactic pieces, the little playlets, the dialogues, aphorisms, even the Lindbergh radio choral, contained in the Lehrbücher or Textbooks form a morality literature, hornbooks of Bolshevik piety, Imitations of Lenin. And for all his sobriety, for all the strenuous simplicity and earnestness and angularity of his manner, Brecht remained all poet—in the old-fashioned sense which he tried to repudiate—and when he put Lenin’s precepts into poetry he transformed them into parables and their settings into mythology. Whether or not this made Brecht a successful revolutionary poet cannot be discussed here, but it was certainly in harmony with the particular style of devotion which Stalinism instills in its faithful.

The mutations of Stalin’s line have had a considerable effect upon Brecht’s writing. Especially since Hitler and exile placed him more than ever at the mercy of the Communist Party apparatus for an audience and honorariums. He went along into the Popular Front, submitted to “socialist realism” with the required docility, and put his theories of the “epic” drama on a shelf for future reference, as he himself says more or less in an extenuating note to the “anti-fascist” play Señora Carrera’s Rifles. The tautness of the “epic” manner slackens into more conventional prose, and he began to write poems in something of the old Hauspostille vein. He arrives at a synthesis: loosely cadenced verse, rhymed and unrhymed, heavier, more uneven, less understated and dry than before. The relaxed rhythms seem to express a slackening political certainty. Brecht begins to lament again and to inveigh. He no longer teaches, he is no longer so positive. But his old skill is still there: he remains as quick and as sure in his sensitivity to language as an animal in its instincts. He can still write a poem like the Verschollener Ruhm der Riesenstadt New-York or Faded Renown of the Metropolis of New York:

…Ach, diese Stimmen ihrer Frauen aus den Schalldosen! So sang man (bewahrt diese Platten auf!) im goldnen Zeitalter! Wohllaut der abendlichen Wasser von Miami! Unaufhaltsame Heiterkeit der uber nie endende Strassen schnell fahrenden Geschlechter! Machtvolle Trauer singender Weiber in Zuversicht Breitbriistige Manner beweinend, aber immer noch umgeben von Breitbrustigen Männern!5

Here Brecht is an outspoken parodist once more. It would be difficult to specify just which of several elegiac manners he is parodying, yet we are definitely aware that he is parodying something. Because what is being parodied is so obscured, the poetry becomes, as always, very much Brecht’s own.

It is unnecessary, no doubt, to point out that Brecht is much better known as a playwright than as a poet pure and simple. He began his career in the early nineteen-twenties as a writer of Expressionist plays in prose, whose savage power and originality soon set him apart. Poetry seems to have been a side issue at first. Yet it was largely due, I believe, to the fact that Brecht was a poet and wrote verse with conscience that he was able to develop boldly and to become the writer of Dreigroschenoper and Die Heilige Johanna der Schlachthöfe, and so the unique force which he is. To say this is almost equivalent to saying that Shakespeare would never have been what he was had he not written verse, but we have become too much accustomed lately to accepting the drama as entirely independent of poetry. It is poetry that “sparks” Brecht’s work, whether in verse or in prose. His instincts and habits as a poet enforce the incisiveness, shape and measure which characterize almost everything he does. What is remarkable is that this sense of form is part of Brecht’s originality and not a constraint upon it, for it creates forms as strong—in Brecht’s hands—as those it violates.

Brecht’s gift is the gift of language, and this gift communicates what seems to me the most original literary temperament to have appeared anywhere in the last twenty years. It is Brecht’s originality that I want to emphasize, not simply as a virtue in itself, but as a germinative influence, as something that can deflect the course of poets in English as well as in German from over-graced and backward provinces to fresher and richer territories.

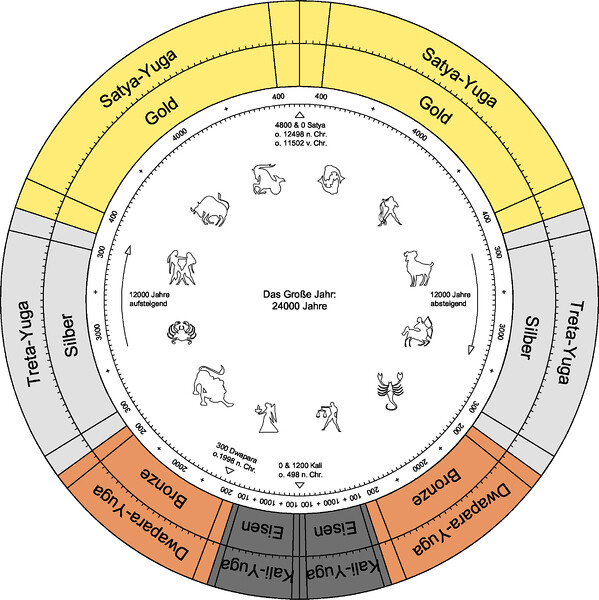

Clement Greenberg, “Bertolt Brecht’s Poetry,” in Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 1: Perceptions and Judgments, 1939–1944, edited by John O’Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), pp. 49–62. Originally published in Partisan Review (March-April 1941); A&C (substantially changed).

came to the logical conclusion and died a hero’s death. The war was not quite over yet, it caused the Kaiser pain to have his soldier die: it seemed ahead of time… And they immediately took the soldier along, the night was blue and fine. You could see, if you wore no helmet, the stars at home. They poured a fiery schnaps into the rotten body and hung two nurses on his arm and his half-naked wife. And because the soldier stinks of decay, a parson limps to the fore who swings a censer over him so that he can stink no more. In front the music with ching da-da-da plays a merry march. And the soldier, as he’s been trained to do, flings his legs from his arse…. [Author’s note]

I am at home in the asphalt city. From the beginning provided with every moral sacrament: with newspapers. And tobacco. And brandy. Distrustful and lazy and satisfied in the end. I am friendly to people. I wear a stiff hat according to their custom. I say: they are beasts that smell quite peculiarly. And I say: it doesn’t matter. I’m one too… . Towards morning in the gray dawn the evergreens piss, and their vermin, the birds, begin to cry. Around that hour I drain my glass in the city and fling my cigar butt away and go to sleep, troubled. We have sat, a trivial generation, in houses that were held to be indestructible (thus did we build the tall structures of the Island of Manhattan and the thin antennae which entertain the Atlantic Ocean). Of these cities will remain: that which goes through them, the wind! The house makes the eater happy: he empties it, We know that we are transient and that there will come after us: nothing worth mentioning. In the earthquakes which will come I shall not, I hope, allow my cigar to go out because of bitterness, I Bertolt Brecht, strayed into the asphalt cities from the black forests, in my mother long ago. [Author’s note.]

And many were seen with tiger jaws, following the red, inhuman flag …. And with our bodies hardened by rain, and with our hearts seared by ice, and with our blood-stained empty hands, we come grinning into your paradise. [Author’s note]

they sing (preserve these records!) in the golden age! Melody at evening of the waters of Miami! Unceasing cheerfulness of the generations that speed along never-ending streets! Mighty sorrow of singing women weeping trustfully over broad-chested men, yet ever surrounded by broad-chested men! [Author’s note]

And as the war in its fifth spring gave no prospect of peace, the soldier

I, Bertolt Brecht, am from the black forests. My mother carried me into the cities while I lay in her body. And the coldness of the forests will remain in me until my death.

In those years the word freedom fell from mouths in which ice cracked.

The Individual has two eyes: The Party has a thousand eyes. The Party sees seven states: The Individual sees one city. The Individual has his hour: But the Party has many hours. The Individual can be destroyed: But the Party cannot be destroyed. For it is the vanguard of the masses and conducts its struggle with the methods of the classical teachers, which are derived from the knowledge of actuality. [Author’s note

Oh the voices of its women from the phonograph cabinets! Thus did