The first feature of Spaces proposes a taxonomy of four phyla to classify the apartment gallery.

Any reflection on an exhibition space alternative to the white cube would seem to imply some kind of critique of the latter. But this, at least for me, is not necessarily the case. At the risk of seeming conservative or reactionary, or somehow even gleefully politically incorrect, I’ll say that I actually like the white cube. As a viewer, writer, and curator, I like the specific conditions it unequivocally establishes—be it in a museum or gallery space—which, with the exception of the opening (for socializing, networking), is to look at and experience art. For while a certain political correctness implicitly obliges us to condemn the ideological nexus of the white cube as a pseudo-religious perpetuator of mere commodity fetishization,1 it cannot be denied that the vast majority of people who enter galleries do not do so to buy art. What is more, even though gallery conditions tend to foster a certain kind of self-contained art, in a quasi-sacral silence which is as auditory as it is architectural, this environment cannot be found anywhere else. The singular purpose to which white cubes aspire is plain: the serious exhibition and contemplation of art. If this seems doubtful, consider a common, well-meant, yet often unsuccessful alternative: with a handful of exceptions, any time a given space shares a function or purpose (i.e. a music venue, restaurant, or bar), the viewing experience and necessarily the seriousness of the art viewed therein is proportionally diluted.2

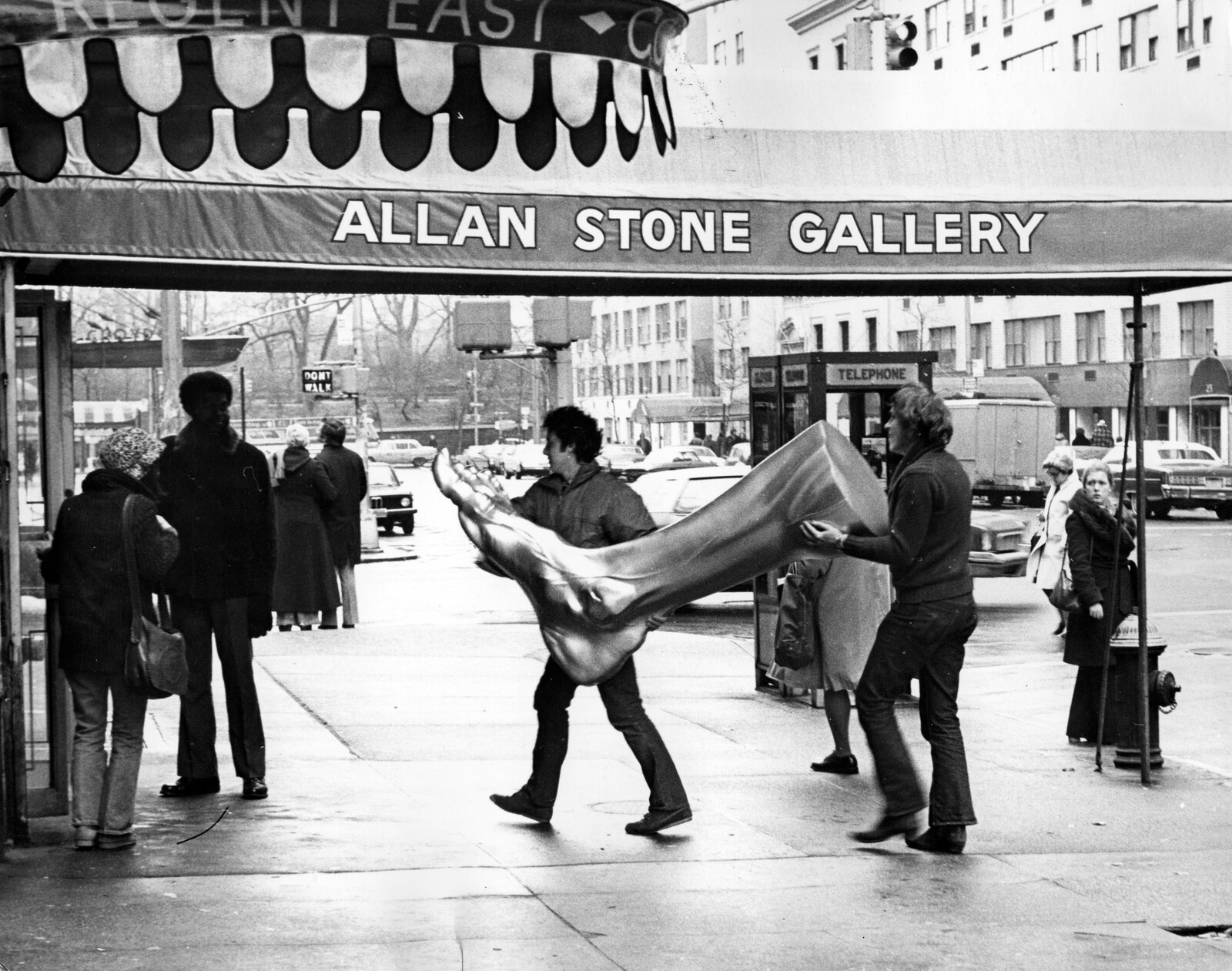

Serious art and serious looking clearly existed long before the emergence of the white cube, so it would be wrong to think that the cube is intrinsic to art, and thus, an absolute spatial convention.3 It virtually goes without saying that it did not magically appear out of proverbial thin air, but was morphologically preceded by a number of developments, the most significant of which is the apartment gallery, a spatial atavism that obviously exists, with a variety of motives and implications, to this day. This evolutionary cycle can be traced throughout several stages in Europe and in particular in New York, most notably in the 1960s, with former galleries around 57th Street and Fifth Avenue. These included Tibor de Nagy, founded in 1950 by John Bernard Myers and Tibor de Nagy, and originally located on 53rd Street, near Third Avenue; the Green Gallery, founded in 1960, directed by Richard Bellamy, financially supported by collector Robert Scull, and located on 15 West 57th Street; or Leo Castelli, who, in 1957, turned the living room of his apartment on the fourth floor of 4 East 77th Street (between Madison and Fifth Avenues) into his first gallery space. Further north, Allan Stone relocated in 1962 to 48 East 86th Street, where he remained for the next 30 years. They all originally occupied apartments-cum-quasi-white cube galleries and were therefore instrumental in the transitional phase to the architecturally codified orthodoxy of the cube. But what is of interest for this article is the current status of the apartment gallery, its whys and wherefores, and nuances of significance.

Taxonomically, there seem to be four basic phyla to the genus of the apartment gallery at the moment. First among these is what could be called the éminences grises. Abundant in New York, they are found primarily on the Upper East Side in majestically multi-storied, largely unmodified (i.e. wainscoting intact) townhouses, and as such occupy a somewhat mysterious position that is at once august and as nebulous as an offshore bank.4 I am thinking of everyone from Hauser & Wirth on East 69th to Luxembourg & Dayan on East 77th to John Graham & Sons on East 67th, among many others. This aura of nebulosity is the byproduct of a combination of things: a willful geographical marginalization (uptown), which, merged with the ambiguity of the domestic privacy of the townhouse with a seemingly public service, translates into an implicit bracketing of that public service, and finally an ostensible tendency to traffic in the secondary market, which comes with all the murk such dealing traditionally seems to entail. Meanwhile, the grouping of éminences grises can be seen to operate in a very different way on the other side of the Atlantic.

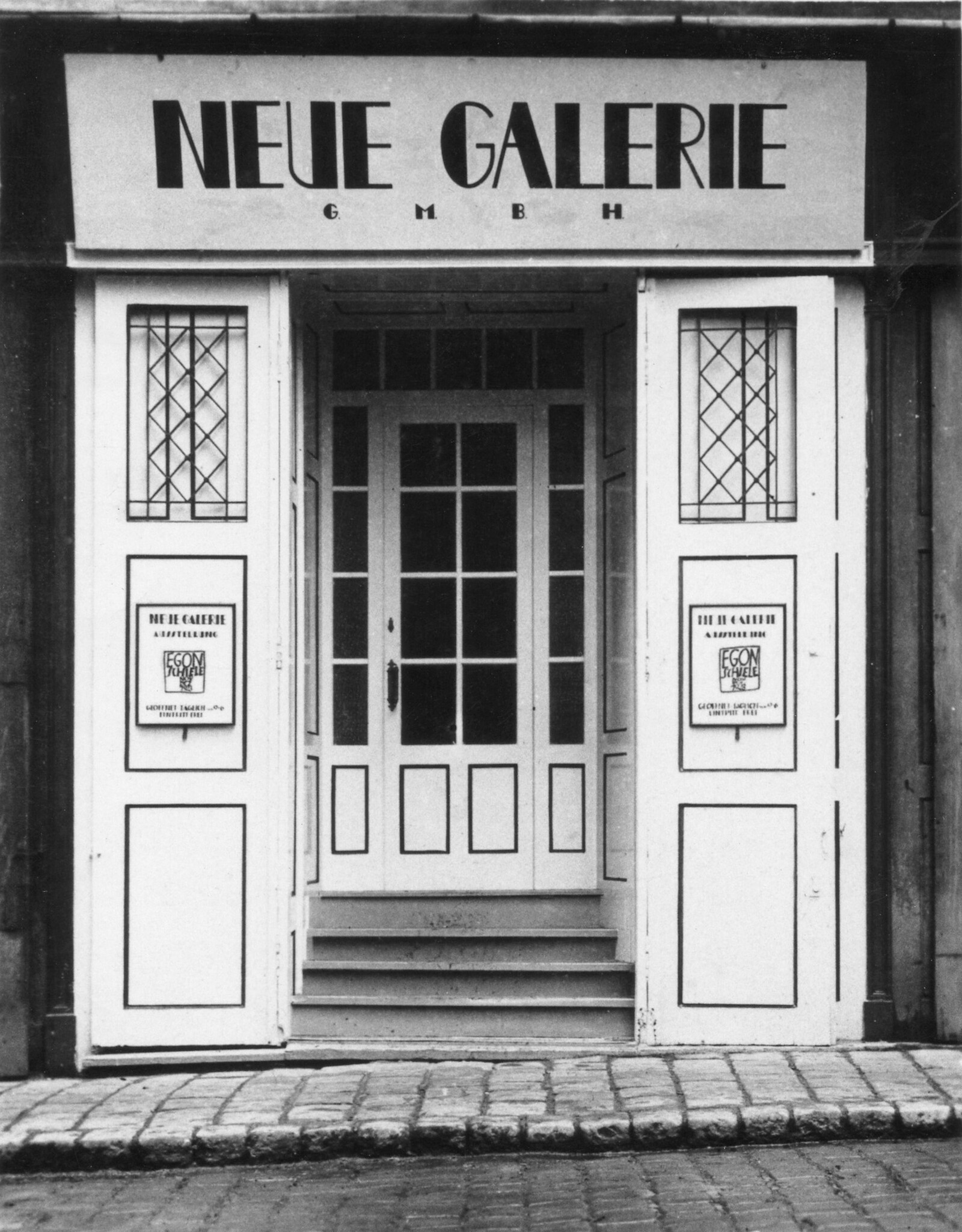

With the exception of Berlin, one of the dominant signifiers of the apartment gallery in Western Europe is bona fide seniority, in that those galleries located in apartments often antedate if not the white cube itself, then its codification. The most distinguished example is arguably the oldest commercial gallery in Europe: Galerie Nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder. Originally founded as the Neue Galerie in 1923 by Otto Kallir-Nirenstein (who later emigrated to New York and founded the Galerie St. Etienne on 57th Street), it was taken over by the Catholic priest Otto Mauer in 1954, who rechristened it the Galerie Nächst St. Stephan. In 1978, Rosemarie Schwarzwälder became its director and, in 1987, its owner. What is remarkable is that throughout these many vicissitudes, the gallery has remained in the same spacious third-floor walk-up apartment in Vienna’s center, retaining both its domestic character, with a tiled wood floor, while nominally conforming to the exigencies of the white cube, with white, unadorned walls and fluorescent overhead lighting.

Secondly, there is the apartment gallery as provisional or transitional space. In this genus, a given gallery starts in an apartment, but moves into a proper cube, or some variation thereof, later on. This is less of a position than a matter of time and a question of convenience. Never mind that galleries that have passed through this process are too numerous to list here. However some notable examples which started in apartments include Warsaw’s Raster Gallery, founded in 2001 by art critics Łukasz Gorczyca and Michał Kaczyński, and from 2003 until 2011 located in an apartment on the top floor of a semi-run-down late 19th-century building; Office Baroque, founded in 2007 by Marie Denkens and Wim Peeters, originally located in an apartment on Harmoniestraat in Antwerp, before moving in 2013 to a former brewery in Brussels, or São Paolo’s Mendes Wood DM, founded by Pedro Mendes, Matthew Wood, and Felipe Dmab, which started in 2010 in the first floor of a building in the Consolação district in São Paulo. Mexico City’s kurimanzutto—conceived by Gabriel Orozco and founded in 1999 by José Kuri and Mónica Manzutto—did not have a fixed location during its first nine years of activity, presenting exhibitions in places as diverse as an indoor market stall, an airport, an amusement park, and also in the same building as Kuri and Manzutto’s own apartment. This phyla, and the following, are also subject to a strange law, which has it that the present often erases the past, by which is meant that if a space moves or changes functions (i.e. project space to commercial gallery), its history, no matter how unusual or radical, is generally eclipsed by its present. In other words, you don’t get to leave your apartment and take it with you.

Thirdly, there is the project, independent, or artist-run space. The line between this and the former is a bit blurry, because in some cases project spaces turn into white-cube galleries, and otherwise because the impetus behind its election of nontraditional, domestic architecture might also be one of convenience, or, better said, budgetary limitations. But the main difference lies in the question of longevity. Intrinsically speaking, the independent or project space has a much more limited life span than any other space, due primarily to the fact that (ideally) artists get too busy to keep running it. As such, this kind of space is rarely, if ever, destined to last. Their occupation of the apartment can assume any number of guises, from the unmodified (furniture intact) to the white-cubified. Two excellent recent examples of the latter are Mexico City’s erstwhile Preteen and Chicago’s recently decamped Queer Thoughts, neither of which exist as such any more. Preteen, founded by Gerardo Contreras in 2008, was initially located in Hermosillo, in Colonia Periodista, before moving to Colonia San Rafael in 2011 and becoming itinerant at the beginning of 2014. Queer Thoughts, founded by artists Luis Miguel Bendaña and Sam Lipp in 2012, was originally situated in the couple’s apartment in Pilsen, on Chicago’s Near South Side, moving to New York at the beginning of 2015. Installing standard fluorescent lighting and painting the designated exhibition spaces entirely white, these spaces borrowed the architectural rhetoric of the white cube not with the intention of fashionably aping it, but of presenting work in the clearest possible way despite the context. In doing so, it could be said that these organizations have thrown down the gauntlet of serious, low-budget professionalism.

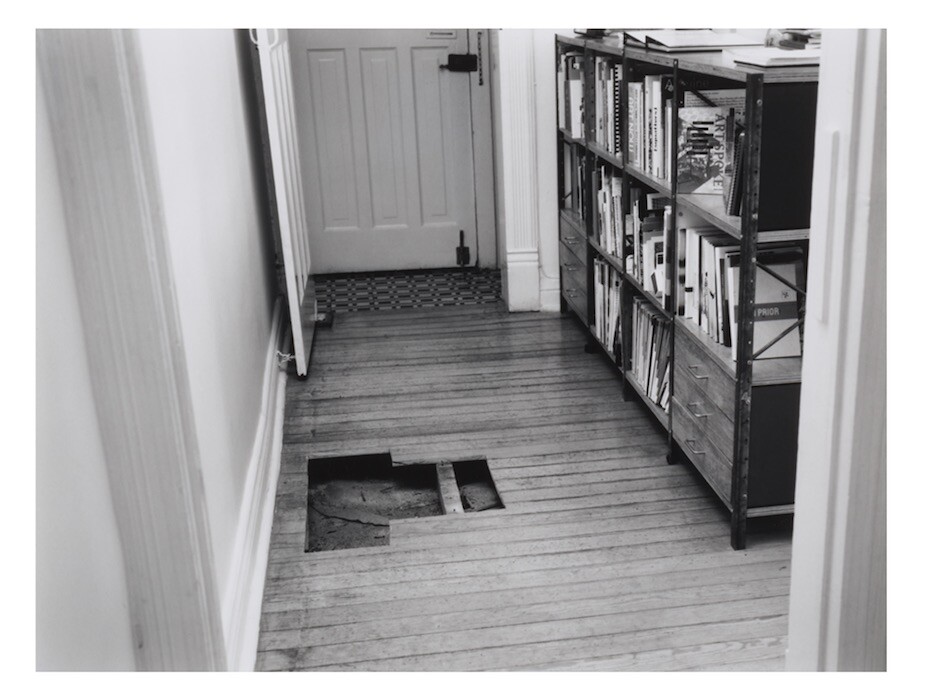

Finally, the fourth and final phyla of the apartment gallery could be called the “fuck it” phyla. The acme of cool, this singular subcategory is where the apartment gallery becomes a real, if provocative position. This phyla merits its singular moniker by virtue of a given gallery’s apparent indifference to its architectural context, and by extension, the traditional conventions of exhibiting art. The motives for such cavalier dismissal of said conventions may vary, but the effect tends to be one of urbane revolt. The best example of this phyla is probably Berlin’s Isabella Bortolozzi. Having recently expanded to include two new spaces, Bortolozzi moved to her main gallery in 2007, a first-floor apartment on Schöneberger Ufer. Not only has Bortolozzi made no effort to modify her space, she has left the dark wood paneling and inset cabinetry that came with it fully intact. As such, by virtually any standards, her space would seem unfit for the presentation of contemporary art. Indeed, it was as if she were deliberately handicapping her artists, as if to state: “My artists are so good that they can make a great exhibition, anywhere, including this sort of ‘gallery’”.5 (This phyla naturally blurs into other categories—quite simply, the unmodified, or even better, fucked up, as in the case of New York’s Reena Spaulings, whose space is a white cube inserted into a battered interior with original, decades-old architectural details and window panes untouched). All that said, the fuck-it phyla necessarily requires a solid base of cultural capital in order to get started (it will be remembered that Bortolozzi did indeed start in a small white cube near Jannowitzbrücke), a pedigree, and/or a very canny program.

When all is said and done, is there a moral to this brief taxonomy? Is one better than the other? (The cube or the apartment? The chicken or the egg?) If anything, the white cube—bless its inimitable specificity—is obviously far from the exclusive mode of architecture for display. As cursorily sketched out here, its evolutionary antecedent remains rich in alternatives and possibility. At once traditional, exotic, limiting, and beguiling, it is capable of fertilely bending and scrambling many of the codes that govern exhibition making.

Few statements better embody this position than Simon Sheikh’s closing remarks to his brief reflection on Brian O’Doherty’s classic Inside The White Cube. Sheikh writes: “Gallery spaces and museums are still white cubes, and their ideology remains one of commodity fetishism and eternal value(s)…” Simon Sheikh, “Positively White Cube Revisited,” e-flux journal, no. 3 (February 2009), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/positively-white-cube-revisited/.

No exhibition space seems more congenitally dogged by this equivocalness than Paris’s Palais de Tokyo. My simplistic formula notwithstanding, it is not clear exactly why this is. Perhaps it is a combination of its indomitably monumental architecture, which has been repurposed to show contemporary art, and the decidedly casual ethos of the place, which seems to encourage “hanging out,” as if idleness and even anomie were somehow conducive to looking at, and maybe even equivalent to, producing art.

Never mind that many a biennial has produced many a great site-specific work.

Incidentally, this analogy of the offshore bank is perhaps not as far-fetched as it might initially seem. For in keeping with the spirit of the intentionally limited visibility of the extra-national banking industry, the gallery Luxembourg & Dayan “respectfully declined” to provide any images to illustrate this text—and that is without even having read the text.

This position becomes especially flagrant in Berlin, where the apartment gallery is so widespread that it accordingly fills all of the above categories, with some slight perversions (I’m thinking of, say, Galerie Buchholz in West Berlin, which assumes all of the characteristics of an éminence grise without necessarily being one), from Bortolozzi’s neighbor, Esther Schipper, who has essentially transformed an apartment into a white cube, to younger galleries like Dan Gunn or Lars Friedrich, who occupy or occupied simple, no-frills apartments.