On November 17, Abu Dhabi Art opened to its VIPs: an event so popular authorities had to redirect traffic off the highway to a new exit. Now in its seventh year under this name, the art fair of the United Arab Emirates’ capital city hosts a smattering of blue-chip galleries—Lisson, Hauser & Wirth, David Zwirner—as well as good lesser-known galleries from beyond art’s Western power centers, like Le Violon Bleu from Tunis or the Third Line from Dubai. It is held every November, and rather pales in comparison to the larger and better attended Art Dubai, in March. The local collecting scene is still forming, and one of the major buyers at the fair is the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, part of the trio of future museums—the others being the Louvre Abu Dhabi and a national museum designed by Norman Foster—whose promise dominates thinking about art in the city.

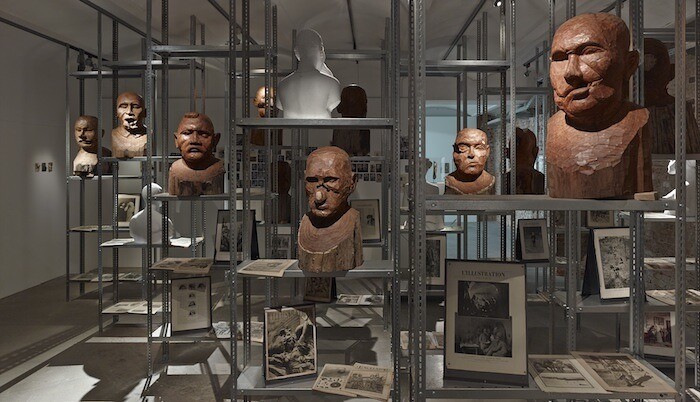

A number of the panel discussions at the fair revolved around the new museums, including the starry talk by Guggenheim director Richard Armstrong, outgoing British Museum director Neil MacGregor, and Agence France-Muséums chair Manuel Rabaté (standing in for Louvre president Jean-Luc Martinez, who stayed in Paris because of the events there).1 The museums—the project of a new state that wants to make its cultural mark—have been the subject of a fair amount of controversy. The Louvre Abu Dhabi is now nearly finished, on a site just beyond the art fair, with construction 24 hours a day in order that it will hit its oft-receding target of opening next year. Ground has not been broken on the Guggenheim but the museum has been collecting assiduously, and at the art fair it announced new acquisitions ranging from a 1973 Warhol Mao to a 1989 Alighiero e Boetti Mappa, and from Rasheed Araeen’s Chakras (1969–70/87) to Akram Zaatari’s Studio Scheherazade (2006) and Kader Attia’s Act 2: Politics. The Repair’s Cosmogony (Die Weltentstehungslehre der Reparatur) from 2013: work that tells of the meetings of different cultures, as well as focusing on work from the Middle East, Turkey, and North Africa. The Sheikh Zayed Museum is next to be built: part of a project that not only includes the museums but also a vast reterritorialization of Saadiyat Island’s desert land, which will become a complex of villas, shopping malls, museums, and open, asphalted areas.

The United Arab Emirates are the subject of rampant stereotyping in the West, and the longer you are here the less confident you feel about reiterating these assumptions. It would be easy, for example, to write a report about this fair that conforms horribly to Abu Dhabi clichés—perhaps noting that the VIP opening was delayed by over an hour because it had to wait till the visit of the Royal Family and, before that, the Ladies’ Preview (the sheikhas and their entourages) was finished—while in reality the extreme wealth of the Emiratis is only one story among many. The UAE also includes middle-class Western professionals saving for mortgages back home; long-term ex-pats from elsewhere in the region; a largely Indian lower middle class; Filipino, Nepali, and Indonesian service workers; and the Indian and Bangladeshi laborers on the construction sites. There’s a sizeable middle ground between the Ferrari-drivers and those in the construction camps.

The situation culturally is also more diverse than one might imagine, and there is a sense of its being a crucial moment for the contemporary art scene. There is a host of new developments as well as—perhaps more tellingly—curiosity about the past, as often happens at a moment of consolidation. The UAE pavilion at Venice, curated by Sharjah Art Foundation director Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, looked at Emirati artists from the 1980s to the present; the current show “1971,” at the Farjam Foundation in Dubai, starts its narrative from 1971, the year the United Arab Emirates was founded; and the Sharjah-based Barjeel Foundation presents a year-long series of four displays from its collection at the Whitechapel in London. “Emirati Expressions,” a biennial exhibition that runs alongside Abu Dhabi Art (literally alongside it, in a gallery space in the same building), focuses this year on the social clubs of the UAE as proto-community-led art institutions. There is also the sense of a local scene forming as more artists return after studying to live and work in the UAE, rather than staying abroad.

Abu Dhabi Art was also the peg for a number of new spaces opening, such as the art and design space Warehouse 421 in Abu Dhabi, with an outdoor concert area, pop-up design boutiques, and a show of photographs collected from Emirati women of their parents—contesting the notion of the UAE as a place without a past. Magnum photographer Susan Meiselas served as an advisor to the project, and noted how some of the students who donated the photographs were surprised to see the women of the past without the veil: “There was a sense of discovery about their own society.” In Dubai, Alserkal Avenue, the curated gallery community, is in the midst of opening a 13.5 million dollar expansion, which will provide new gallery space for the Alserkal Avenue organization (confusingly, it is both an organization and a place), an art cinema, a black-box theater for community programming, as well as new restaurants and galleries. A foundation dedicated to the post-minimal holdings of the late French collector Jean-Paul Najar opened there last week, as did satellites of Leila Heller (New York) and Galerie El Marsa (Tunis).

Indeed Alserkal Avenue is an interesting case study in the development of new art scenes. It sees its role as much as a purveyor of content as—that horrible word—a hub for artistic activity in the city: a place for people interested in art (and design) to convene. While a lot of the investment in art in the UAE has been top-down—the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi and Louvre Abu Dhabi are as geared towards tourists as local artistic communities—small to medium-scale organizations have been harder to nurture. As elsewhere, they are systemically difficult to fund, requiring investment in young or little-tested artists who, if they make it big, will do so elsewhere, with those organizations reaping the rewards financially or in terms of profile.2

Sadly for my attempt to dispel clichés about the region, Alserkal Avenue’s funding strategy is not easily replicable and runs smack-dab into a heap of wasta, the Arabic term meaning “power and influence.” Alserkal Avenue began as a group of warehouse spaces in the industrial area of Dubai, on land owned by Abdelmonem bin Eisa Alserkal, a member of a well-established Dubai family. Alserkal’s patronage of the Avenue, where the galleries happened to have settled, was opportunist in the best sense. Realizing what was happening, he began sponsoring curated art programs to complement the commercial activity, and two years ago the Alserkal Avenue arts organization was officially launched. So far it has made some strong, serious choices, such as projects by Maria Thereza Alves (last March) and Mary Ellen Carroll (next March).

A query I hear often is how the Emirates might distinguish themselves from one another in terms of cultural profiles. It’s a funny question, suggesting a bird’s eye view of an art scene’s development rather than, to mix metaphors, one from the grassroots—though perhaps it echoes in the halls of other countries with small cities and admirable (or once admirable) public funding, like that of the Netherlands. It reflects the fact that, as far as institutions go, the UAE is a tabula rasa: a SimCity-like project of urban planning. As institutions now embed themselves, and as other initiatives arise organically, what’s clear is how important it is that directions flow both ways. Though the UAE boasts of its world records—the biggest building, the largest carpet, the biggest chandelier—where art is concerned it’s also best to scale down: scale down and let the art scale up.

The British Museum is the “consulting partner” behind the Sheikh Zayed Museum, which will tell the story of the founding of the UAE.

This was the argument of Size Matters, a paper produced by the London network of small-to-medium-sized art organizations Common Practice.