In curating “Letter from Istanbul” at Pi Artworks, London, Morgan Quaintance combined multiple approaches to examine the cultural, social, and political life of Istanbul. He expanded the format of the exhibition to open a direct dialogue between artworks and diverse materials and documents, while also including radio broadcasts and a documentary film. In this conversation with Filipa Ramos, Quaintance reflects on his intentions, interests, and methodologies while also considering the limits of grasping, displacing, and presenting the socio-cultural context of a city in the form of an “informal dispatch.”

Filipa Ramos: When I first visited “Letter from Istanbul,” a group of students were using the public space of the show to reflect upon it. I was particularly interested by one overheard comment, in which a woman maintained that “it’s difficult to know where the curator ends and the art begins due to the combination of documentation and artworks.” So maybe we could address this first: what was your intention in presenting journalistic materials—music pamphlets, political documents, scenes from various demonstrations, books, and texts—alongside artworks?

Morgan Quaintance: I think at the root of “Letter from Istanbul” was the impulse to curate an exhibition as abstracted city report or informal dispatch. But, instead of having key sociocultural, political, and historical information stuck up as expository wall texts, I used images, documents, and books to indirectly point to those details.

I should also say that the authored works identified as art were themselves a mixture of reportage, video activism, and, for want of a better expression, “contemporary art.” I don’t really see a massive distinction between them, but it’s important to say that some of the works hadn’t been presented in a gallery setting before. My intention in bringing them together was to ignore whatever interdisciplinary hierarchical distinctions there may be and to take advantage of the heightened mode of spectatorship that can exist in the art exhibition context. So work that might only be seen online and perhaps inattentively scanned as video journalism could be considered without all the distractions that come with staring at browsers on a laptop, smartphone, or tablet.

FR: It is this variegated approach to a context—the way in which Istanbul’s music culture, historic recollections, political discourses, activisms, literature, theater, and subjective accounts are woven together—that emerges as the exhibition’s strength. The artworks on view take part in, without dominating, this scenario.

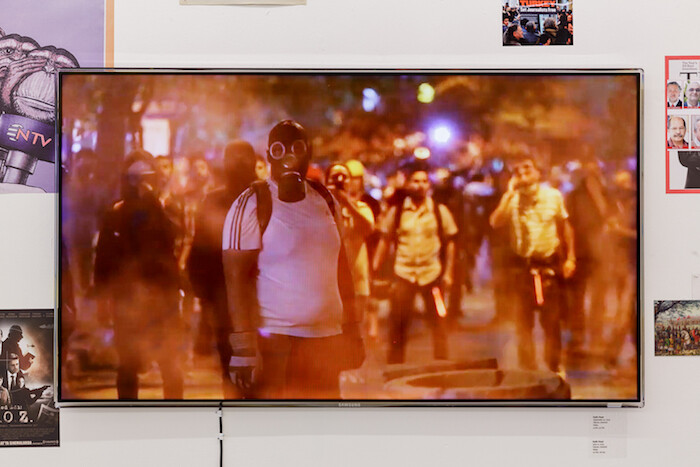

MQ: A good example of what I wanted to achieve was provided by two works from filmmaker and video activist Fatih Pınar (Gay Pride in Istanbul [2014] and September 10 [2013]). They were placed among a constellation of images and materials I’d chosen, and both videos are of people protesting or marching in the streets around Taksim Square and Istiklal Street in Istanbul’s Beyoğlu area. On one screen there was footage of demonstrations that followed the Gezi uprisings in May 2013, and on the other footage of the Gay Pride parade in 2014.

The materials placed around the Gay Pride in Istanbul work spoke to gay cultural history through images of Zeki Müren (seen by many as Turkey’s first openly gay icon) and Bülent Ersoy (a transgender performer who was persecuted in the aftermath of the 1980 military coup, but is now feted by the government and seems to have conservative sympathies). There were also images of the repression of Pride in 2015, where water canons, rubber bullets, and other excessive shows of force were used by police to disperse the crowd and stop the parade.

A similar rationale was used in choosing the materials that surrounded Pınar’s post-Taksim demonstration footage: images of the construction work that led to the Gezi uprisings, as well as newspaper articles and satirical cartoons from that time. These images blend with ephemera (leaflets and so on) that I gathered while I was in Istanbul during the recent referendum, and these in turn blend with images of people—the Death Metal musicians, for example—that I met for the documentary I was shooting while I was there.

FR: The documentary provides a generous entry point to the exhibition. Visitors are introduced to the people, places, and situations that shaped your research. These moments and events are typically kept behind the scenes of a show, or at best emerge through a series of tightly edited interviews with participating artists. What came first: the documentary or the show?

MQ: The film was shot first, but I always considered the documentary, the exhibition, and the two radio programs I produced for Resonance 104.4FM to be different parts of “Letter from Istanbul.”

The research unfolded over three stages. The first was about delving into books covering Turkey’s past, present, or possible future. I needed to do this to get a working knowledge of Ottoman history, Kemalism, and the transition from secular nationalism to the conservative Islamic modernity of the Justice and Development Party (AKP). In the second stage of research I began to meet and talk to people, armed with that research. The third stage is when the primary and secondary research come together to inform the texts that are written and the questions for interviews conducted. Like most research, it’s important to know a hundred more details than I’ll use, and so all that work may not have been apparent to the casual viewer.

FR: You’ve expanded the format of the exhibition by complementing it with other media—namely the radio programs and the documentary film. When considering the project’s development, I’m interested to learn about the space between its original premise and its final outcome, and the roles that the different media played in its investigation of the cultural and sociopolitical context of modern Istanbul.

MQ: I’m still at that point in the project where it’s really hard to get an objective overview of what’s taken place. That said, I think one of my main reasons for using the documentary and radio programs alongside the installed exhibition was to make sure that people’s actual voices were being heard. Rather than speaking for anyone, I wanted to use my curatorial privilege to open up spaces for artists, sociologists, and citizens to speak, for their experience and firsthand knowledge to come through.

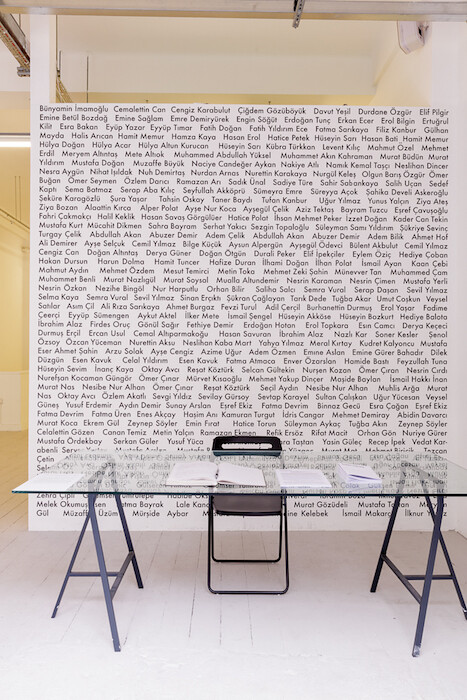

FR: The first thing one encounters when entering the gallery is a long list of names. Not well-known figures—politicians, or artists—but common names, spelled row after row after row.

MQ: These are the names of university lecturers in Istanbul who appeared on decree number 672, issued in the wake of the failed coup of July 2016. After the uprising, the Turkish government instituted a purge of people they deemed to be associated with the US-based cleric Fethullah Gülen, who was accused of plotting the coup. Now, depending on who you talk to, Gülen is either the leader of an Islamic cult or the main figure behind a peaceable international movement to unify science and Islam (via creationism) through soft power channels and civic as opposed to party political engagement. The Gülen movement, which came about in the 1960s and gained ground after the military coup in 1980, was also affiliated with the AKP at the onset of that party’s route to power in the early 2000s.

The purge was announced through a series of online decrees listing the names of individuals to be sacked for their alleged links to Gülen. Hundreds if not thousands of innocent people found themselves cast as conspirators. They were dismissed from their jobs, barred from working anywhere else, and prevented from leaving the country. The sentence issued was one of slow financial, intellectual, spiritual, and most likely physical death.

I wanted those names to be the first thing people see in the space because they are the casualties hidden from public view. I thought about blowing up the front page of the decree to A3 or A2 size and sticking that over a section of the names so that the association would be clear, but it seemed too heavy handed. So instead I stuck the decree on the front table and placed different sections of it in the constellation surrounding Fatih Pınar’s work. I’m not sure how successful this was but, then again, judgments of success or failure on that front would presuppose I had the intention of provoking a set reaction from visitors, and I don’t think I did.

FR: The list is so extensive that the physical size of this group of names—which fills an entire wall—materializes the extent to which the political situation is affecting the lives of citizens. It also reflects on the role that culture in general, and artistic practices in particular, can play in responding to this. Indeed, “Letter from Istanbul” is not the typical exhibition about a city’s cultural scene, in which visitors are given an outline of who’s doing what right now. Instead, it is an attempt to grasp a moment whose past seems impossible to disentangle from its future, but that also reflects on the city’s movements for social emancipation, which now seem quite distant from the current reality. Would you be able to sum up the portrait of Istanbul drafted by the show?

MQ: In curating this show, I definitely wanted to avoid any essentialist portrait of the city. I can, however, speak about certain constraining forces—shaping civic life, urban development, and freedom—that emerged again and again in conversations with people, and were also mirrored in the topics covered in print journalism, sociology, and party politics.

It quickly became apparent that London and Istanbul are both going through accelerated processes of urban development. This is having a detrimental effect on certain positive sociocultural features in each city. London is being transformed into a metropolis of empty, high-rise luxury flats and land-banked homes catering to high and ultra high net worth individuals. In the abstract, the casualty of this process is the multicultural nature of the city; in the concrete, people are actually dying.

In Turkey, as one anonymous interviewee in the documentary states, Istanbul is being turned into a “touristic city,” what he calls a “city without any layers.” You can see and hear in the documentary that the city is in a constant state of construction and, from what I could gather from people, construction is in almost every case synonymous with erasure: not only buildings, but histories, people, emancipatory movements. Life, basically.

In both cities, elements of difference and diversity are being flattened out, and this is frequently a violent process that causes a great deal of harm to a great number of people. I also felt that there were traces of a reductive yet official, contradictory narrative based on reclaiming a mythical, and radically simplified, Ottoman history on the one hand and, on the other, by creating this flattened-out modern city. So Istanbul seemed to be a liminal city, not because of its placement between the East and the West but because it is caught between these two visions.

The sociocultural fallout from that dynamic formed a major part of the exhibition. So, rather than a portrait, one of the things I was aiming for was a snapshot of that present.