Just when certain worn-out frameworks of exhibition making appear to finally become obsolete, they are repackaged and mounted once again. The exhibition “City Prince/sses: Dhaka, Lagos, Manila, Mexico City and Tehran” seems like a throwback to 1990s curatorial expansionism, if not straight up nineteenth-century colonialism. Preliminary questions such as why these cities, why now, why in Paris, are not addressed, and no attempt is made to clarify the geographic focus of the show. The curatorial statement for the exhibition has deftly appropriated the hackneyed language of nonfixity and fluidity and eschews the more anthropological tone of the ’90s. Instead it presents a soft exoticism that is nominally reflexive, sealed in postcolonial lingo, and avoids salting the historical wounds of the local context by its geographic treatment, opting not to include any former French colonies. Therefore, the five cities’ “cultural, political and social singularities teem with numerous narratives which are all side-tracks providing glimpses into their identities, devoid of anything that could be univocal.” Yet the statement makes clear that the dissecting, omnipresent curatorial eye cut through these heterogeneous multiplicities, excavating glimpses into their equivocal identities. From this critical vista, the curator could not only present this multiplicity of positions, but also read though their differences and even manage to access the “side-tracks” of these complex “megacities,” that are “quite clearly” different from each other. But what kind of knowledge can grant this access and the power to decipher idiosyncratic sociopolitical contexts of such dense urban strata, with divergent histories, economic conditions, ethnic diversity, political affiliations, and so on?

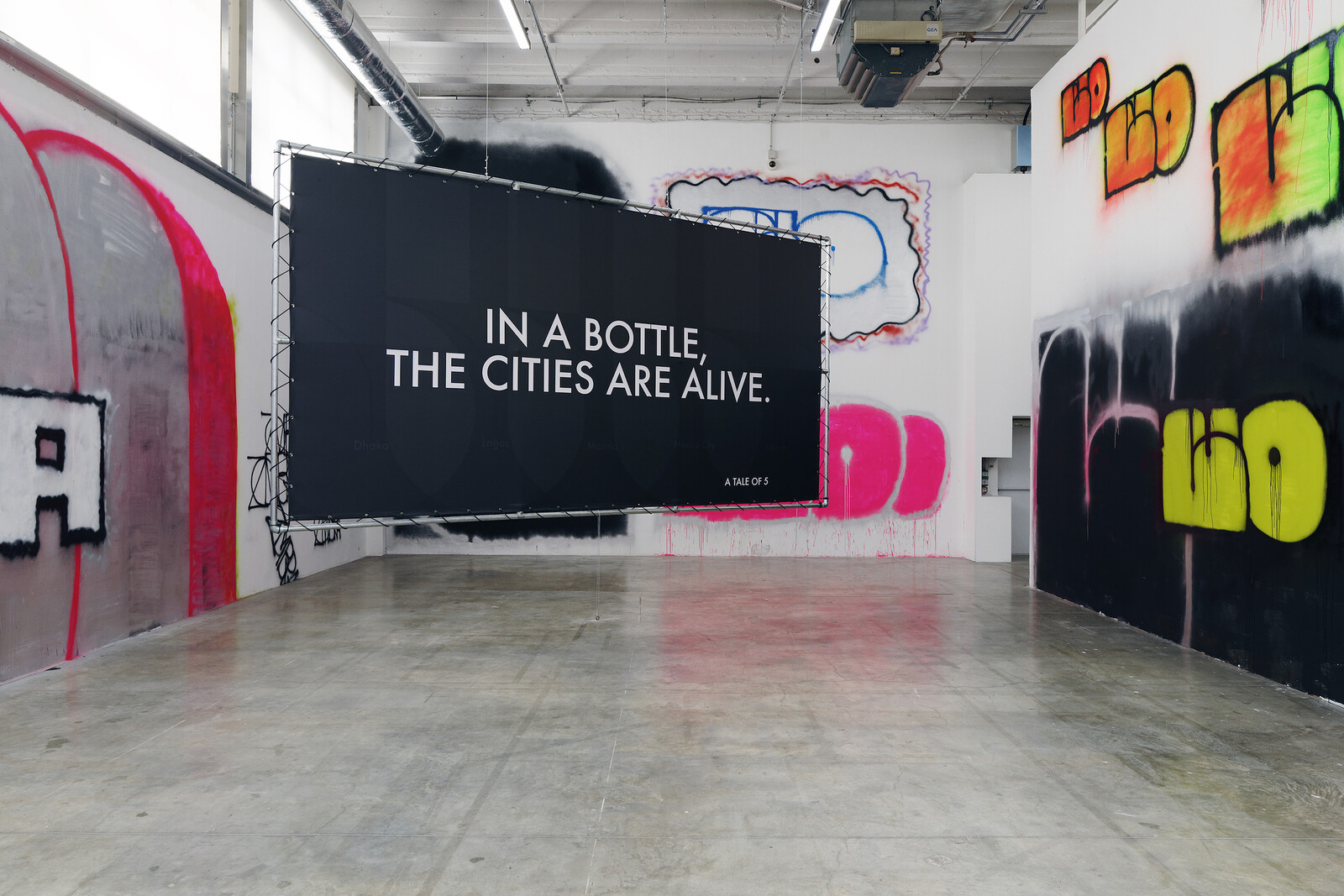

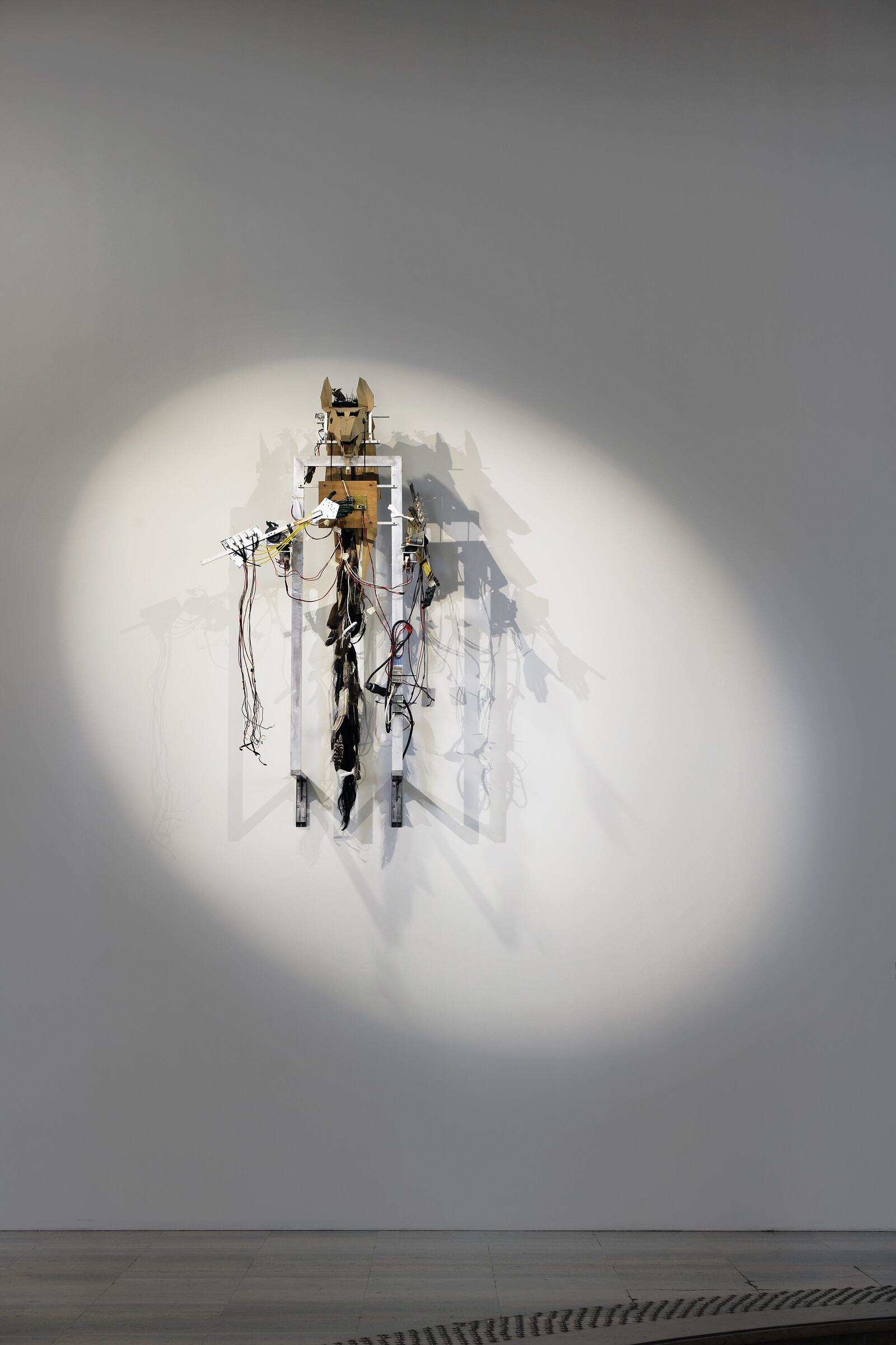

Addressing representational tokenism, Walter D. Mignolo writes, “once upon a time scholars assumed that if you ‘come’ from Latin America, you have to ‘talk about’ Latin America.” Yet if you are coming from Europe or North America, you can “function as a theoretically minded person.”1 Mignolo identifies the institutional discrimination that did not grant the decentered the right to abstraction, and the exhibition demonstrates that such form of bias is not an artifact of the past. Of course, the works in the show challenge the framework of the exhibition and do not support such expired methods of classification and essentialism. Some works respond to aspects of a specific urban experience, but only as raw material, while many others don’t. The exhibition features mostly large immersive installations and presentations, each occupying a room of the post-Bauhaus raw plywood architecture that sprawls across two floors of the Palais. Maria Jeona Zoleta’s Possessed Projxxx Presents: Happy Hours!! Smelly Flowers!!!! Marshmallow CottonCandy Microsluts Aqua-Cheeze(Curlzzz) Sweetcyclone SmileySpaghetti //BabyBabybabybrixx///paradise forlyfe/extralyf//afterlife !!! [fromthefirstdayoftherestofmylife& Urs2] Channeling Cheap Creamycologne Spellcasting by Kreepeemummyklownkraze691989 »» Or dirty I.Scream (2019) resembles an Adult Swim–themed kid’s party or psychedelic children’s parlor; Mamali and Reza Shafahi’s Daddy’s sperm (2019) explores family relations and the interiority of the home and its porous relation to larger social dynamics; Biquini Wax EPS’s reflections on environmental holocaust present an exposed carcass of a shored resin orca that perhaps crossed the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (Sa la na, a yuum, iasis, laissez faire, laissez passer, 2019); Mehraneh Atashi’s whimsical playground of ancient mythology and fables processed through personal history (Flotsam, Jetsam, Lagan and Derelict, 2019); and Fernando Palma Rodríguez’s Techpactia tlen quipanoz ipan Milpa Alta? Do you likewhat is happening in Milpa Alta? (2011), a group of simultaneously futuristic and ancestral robotic figures that reinterpret indigenous knowledge and its contemporary currency, are among a number of ambitious presentations. The works on view are as related to the particularities of a specific locale as issues like family, sexuality, environment, class struggle, etc. could be.

Even as the exhibition’s curators attempt to dodge all the “traps” of the good old blatant exotica, they managed to enter through the backdoor by avoiding any kind of discursive apparatus via recourse to opacity and ambiguity. Yet, what the exhibition fails to consider is that opacity is always situated and provides a powerful theoretical toolbox, developed to resist the violence of colonialism and imperialism, the scientific objectivity that disregarded indigenous knowledges, normalizing and standardizing discourse of modernism, neoliberal extraction, global cultural homogeneity, and so on. Instead, in a moment in which theory has become unfashionable and replaced by image feeds, where curators assume the role of safari guides, Instagram influencers, and aspirational lifestyle proxies, opacity has become a mere loophole for business as usual minus even a pretense of a curatorial discourse.

While a number of artists in the show have been living and working in Europe or North America, they apparently cannot adequately be the “hackers of our responses” to their immediate urban environments such as Paris, Amsterdam, or Los Angeles, regardless of whether their work necessarily responds to the “tissues of contradictions” of a supposed megacity where they were born or lived in at some point. This is not far from the xenophobic rhetoric of the current political climate in the West. The cities without borders are not borderless for most of the inhabitants of the cities featured in the exhibition. Perhaps the “flâneurs of the twenty-first century” are not the artists, as the curatorial text claims, but rather the curators who can butterfly from one sociopolitical enclave to the next on an Expedia dérive and observe the political singularities of their objects of study.

In a discussion after their presentation at the opening of Manifesta 12 in Palermo, Ntone Edjabe, a co-founder of Chimurenga magazine, said (I am paraphrasing) that we need to consider what freedoms are we willing to give up. Perhaps something to mull over before booking the next curatorial itinerary, or organizing the library.

Walter D. Mignolo, “Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and De-Colonial Freedom,” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 26 (July–August 2009): 1–23.