For days, I couldn’t get Charles’s gold supertunica off my Instagram feed. The newly minted king had leveraged gold’s hallucinatory power: he could count on Meta’s algorithm, designed to mine attention. The word “hallucination” was coined by Thomas Browne, to whom the English language owes more than 750 others, including “computer,” “coexistence,” “exhaustion,” and “indigenous.” These disparate expressions of power, currency, and representation coalesce in “El Dorado. Un territorio,” on view at the waterfront Fundación Proa in La Boca, where the Spanish landed in 1536, as the Matanza River—South America’s most polluted waterway—meanders past the art institution.

Developed collaboratively by Fundación Proa, the Americas Society (New York) and Museo Amparo (Pueblo, Mexico) to explore the myth of El Dorado, its multivalence, and its contemporary resonances through the work of Latin American artists, the project comprises three distinct exhibitions. This serial form reflects, according to the organizers, the concept’s core elusiveness and its diverse manifestations around Latin America since 1492. It also refutes the very idea of Latin America—a geopolitics imagined by colonial capitalism and sustained by neoliberalism—by presenting three locally-specific approaches to the myth.

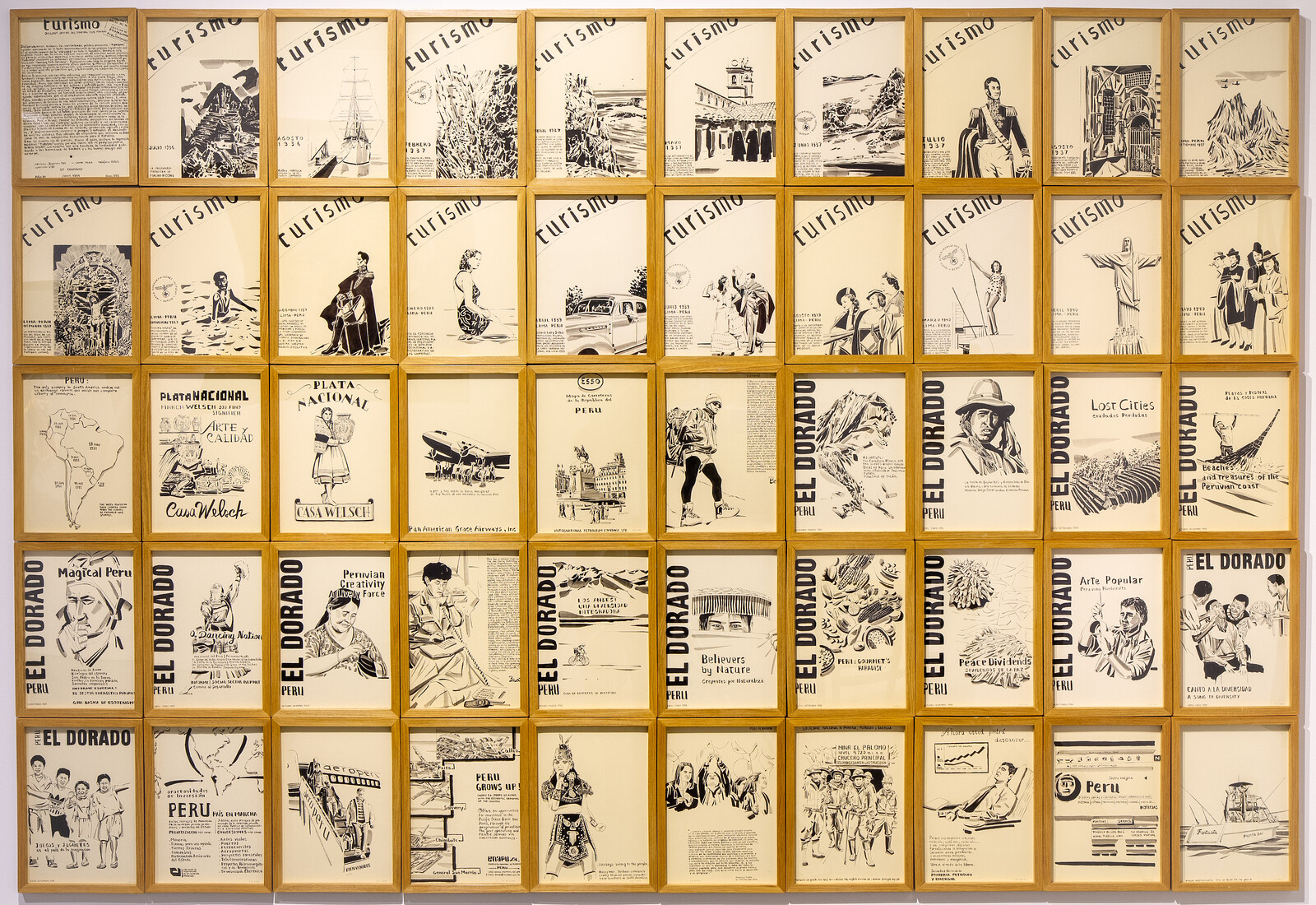

In Buenos Aires, the project’s first iteration brings together works by twenty-seven contemporary and several anonymous artists to consider El Dorado in terms of territory and natural resources. Water buoys the first gallery, casting the myth as a hypnotic voyage. Fernando Bryce’s Turismo/El Dorado (2000) is installed, floor-to-ceiling and five drawings wide, like a totem to Peru’s latest commodity: its own heritage, for consumption by mass tourism. Victor Grippo’s sculpture El Dorado - Huevo de oro (1990/2023) and Clorindo Testa’s installation El espejito dorado (1990) anchor the room, their distressed vessels invoking El Dorado’s footprint. These two works also nod toward Grupo CAyC and curator Jorge Glusberg’s namesake exhibition (1990)—their inclusion swiftly appropriating a local curatorial milestone. Carolina Caycedo’s immersive three-channel video-projection Patrón Mono: Ríos Libres, Pueblos Vivos (2018/2022) envelops the space, casting three adjoining walls into a kaleidoscopic gold-flecked underwater journey.

Parting curtains—and wading through this trance-inducing image flow—we reach the second gallery, where hallucination gives way to a quiet, gold-filtered space. This is the exhibition’s most sensual grouping of works, and a marked digression from its stated path. Swept up in a golden mirage, we are shuttled between spirituality, belief, and materiality. Gold is color, language, symbol, cover, and adornment, this rooms asserts—anything but a metal. Gold monochromes by Mexican artist Mathias Goeritz, Stefan Brüggemann’s gold-leafed palimpsests, and Leda Catunda’s large textile Eldorado II (2018) line the walls, while Olga de Amaral’s seven hanging Estelas (2007/2018/2019) lure us in.

In the middle of the room, skied against a too-busy ceiling and trapped between five cast-iron pillars, Laura Vinci’s Batéia (2014) loses its performative essence and much of its awe-inducing criticality. Instead of the intermittent slow shower of fluttering gold leaves of its initial installation at the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil in Rio de Janeiro, we’re left with a small constellation of barely swaying golden pieces hung reverently out of reach. Gone are the embodied references to the labor, technique, and anarchism of gold panning; pre-empted are the improvised interactions born of wonder and desire; foreclosed are the play and vulnerability of self-organized collective responses. I bet some visitors missed the work entirely. Three religious artefacts, meanwhile, channel our attention to the Church’s gains from colonialism. A Spanish-made, gold-embroidered, nineteenth-century cope recalls Charles’s coronation vestment. Initially, these seem rather gratuitous—beautiful, vaguely hallowed space-fillers. Eventually, however, their purpose comes into view: as seductive decoys used to rewrite the political economy of El Dorado. Walter Benjamin’s remark that “Capitalism is a religion of pure cult, without dogma” haunts this space.

Allow me a short detour: Fundación Proa is a private entity essentially supported by Tenaris and Ternium, two divisions of Techint, a building and engineering multinational whose activities, anchored in steel mining and production in Latin America, encompass manufacturing, oil and gas, health care, and technology, media and environmental remediation ventures. Ternium’s and Tenaris’s logos grace the exhibition’s title and are twice featured in the exhibition catalog. And Fundación Proa shines on the Community Relations section of Techint’s website, where the company boasts of its forty million US dollar investment in education and culture, reaching over 400,000 individuals. If gold was El Dorado’s mirage, our social imaginaries are its new horizon.

In the interview published in the catalog, exhibition curator Adriana Rosenberg repeatedly marginalizes the concepts of extractivism and exploitation by zooming in on their limitations. She even goes so far as to expressly exclude metal from the domain of natural resources. Beyond wishful denialism, however, little more than fool’s gold is offered: a generic gloss on Argentina’s southern specificity, pious reverence of the land’s fertile generosity, and the diversity of Indigenous knowledges, which the selected works are called on to represent. Deeply political, this conceptual contortion is no match for the works’ uncontainable polysemy. And since the repressed does return, we are called on to share our experiences.

Most directly addressing the exhibition’s stated theme—territory and natural resources—the next two galleries walk a tightrope by nearly, and spectacularly, reducing natural resources to agriculture and bioeconomy. Academic and populist impulses come together in these rooms. The transposition of the theme to a space casts the works as evidence, which visitors are enticed, if not coaxed, to share as “experience.” This transposed index reduces richly multivocal works to a checklist of the continent’s flora and foodstuff—potato, corn, pepper, cacao, coca, rubber—and cochineal. Soil is also made to stand for territory. Many of these works are hemmed in while significant real estate is reserved for Instagrammable moments—vinyl-lettered Proa handles included. Generous frontage allows us to claim massive silver wings (c. 1870) for a selfie. The exquisite craft, intensive labor, and traditional knowledge of their anonymous artist(s) get lost in our angelic pictures. So do the toil and the trauma inflected on soil by silver extraction. Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s exquisite copper works profess their resilient craft, defy the exhibition’s metal aversion, and assert social conductivity.

In the last gallery, a still excerpted from Marta Minujín’s six-part photographic performance with Andy Warhol El pago de la deuda externa argentina, “el oro latinoamericano” [Payment of the Argentine Foreign Debt, The Latin American Gold] (1985), is enlarged into a wallpaper backdrop for two chairs and piled ears of corn, inviting visitors to remake the picture. This strikes me as a rather cynical curatorial interpellation. Sit here and you, too, can be Minujín repaying Warhol/USA. Step in, snap, and post the picture: the criticality of Minujín’s performance conveniently evaporates. So does its historical specificity: the military dictatorship’s sharp growth of Argentina’s foreign debt, which still plagues the country’s economy. Which side did you choose? Debtor or creditor? Either way, your volunteer labor grew the institution’s follower base and cultural capital.

In “El Dorado. Un Territorio,” the myth is alive and well. The exhibition’s design and distribution of space unintentionally demonstrate that attention and its twin, distraction, remain El Dorado’s currency. Power always seeks to monopolize attention, as the coronation reminded us, using gold as a means to an end. In Argentina, a country blighted by disastrous inflation and facing critical elections, attention and diversion are indeed solid gold.