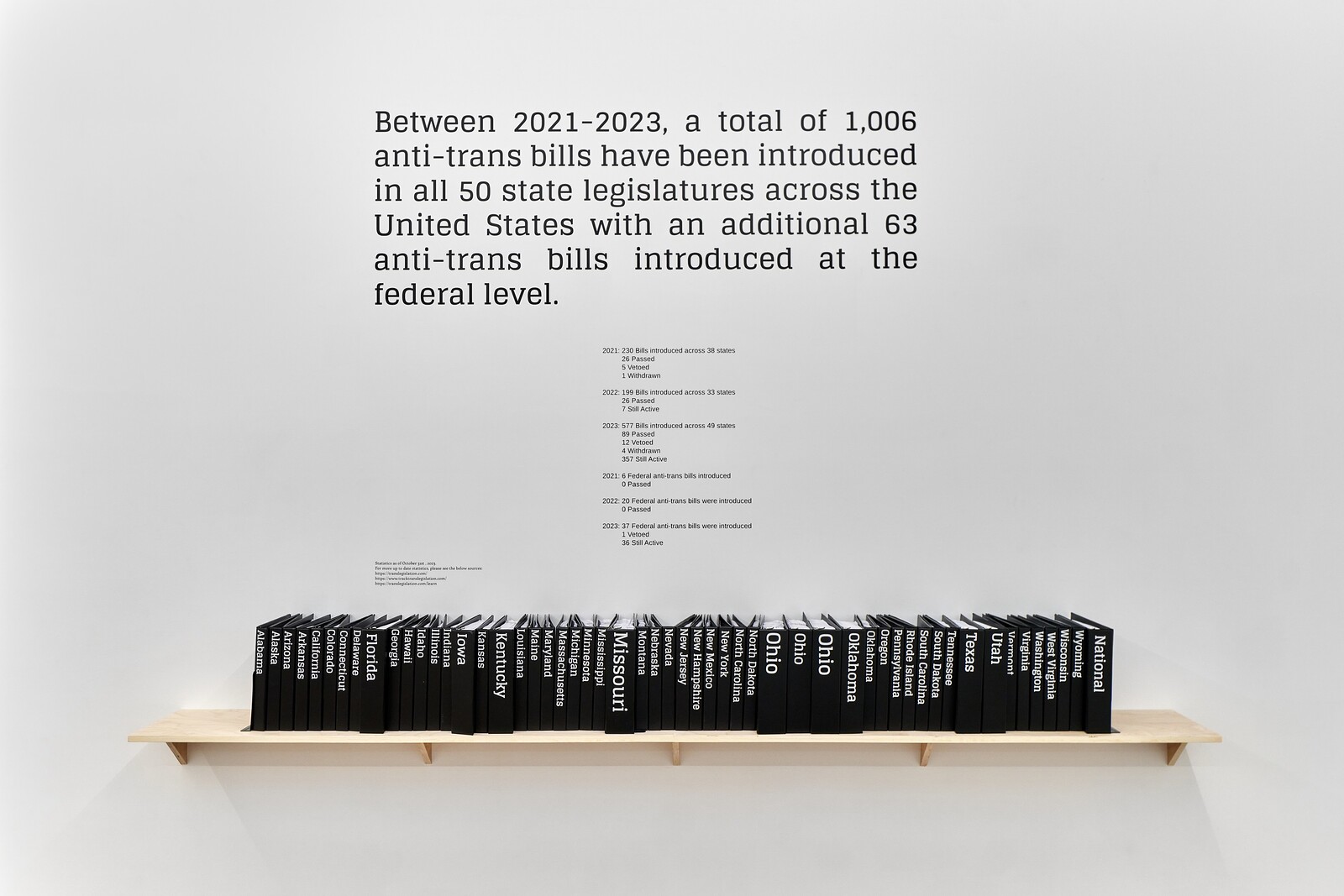

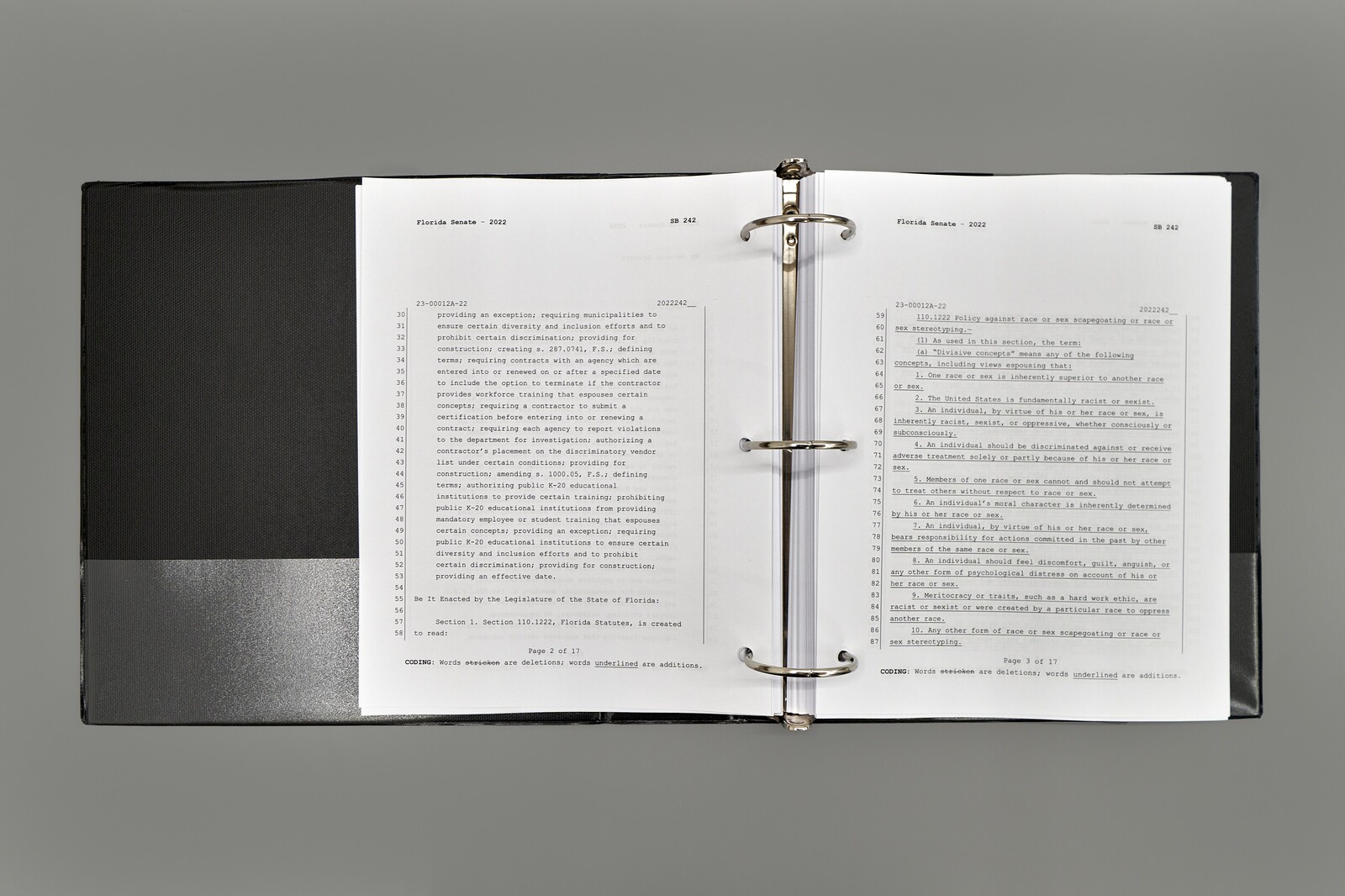

The first work that one encounters on entering Andrew Kreps’s gallery might be mistaken for an extension of the gallery’s commercial operations. Trans Bills (2023) consists of fifty-four black ring binders, arrayed on a shelf to the left of the front desk, labeled with the names of states that have passed legislation restricting the rights of trans citizens. The work’s blandness is perhaps the point. Quietly running in the background of clownish Republican performances of parental rights and viral videos of religious zealots is a legislative machine producing the reams of paper progressively restricting the rights of trans people to work, receive medical care, and live basic social lives. In a mere two years, 1,006 anti-trans bills have been introduced by state legislatures. An additional sixty-three have been introduced at the federal level.

At the back of the first-floor gallery is a 47-minute single-channel video of a trans prom organized by four teenagers as both an adolescent rite of passage and a protest—two things that are, for many trans youth, inseparable. The footage is visible from the gallery’s entrance, and the contrast between the young faces and the scale of adult animosity ranged against them is the show’s most valuable and striking visual statement. Even for the politically sympathetic viewers likely to see the show, this contrast is useful. It is a reminder that legislators perceive smiling teenagers as existential threats. The reaction, which seems at first to be insane and outsized, is a measure of how politically important (read: threatening) a thriving trans community actually is.

The mirror ball and neon sculptures that decorate the gallery—lush, floral arrangements named for evocative colors like “Marshmallow Bunny Pink”—make unfortunately bland pronouncements given the importance of the event that they support. Unlike the staging of a trans prom, slogans such as “be you” are already thoroughly assimilated into an attention economy based on self-differentiation and individuality. While aesthetically appropriate to the filmed event and more than pleasant to behold, the textual choices alienate rather than connect the sculptures to the resistance the show documents and amplifies by using signifiers that are too easily transferable to any group.

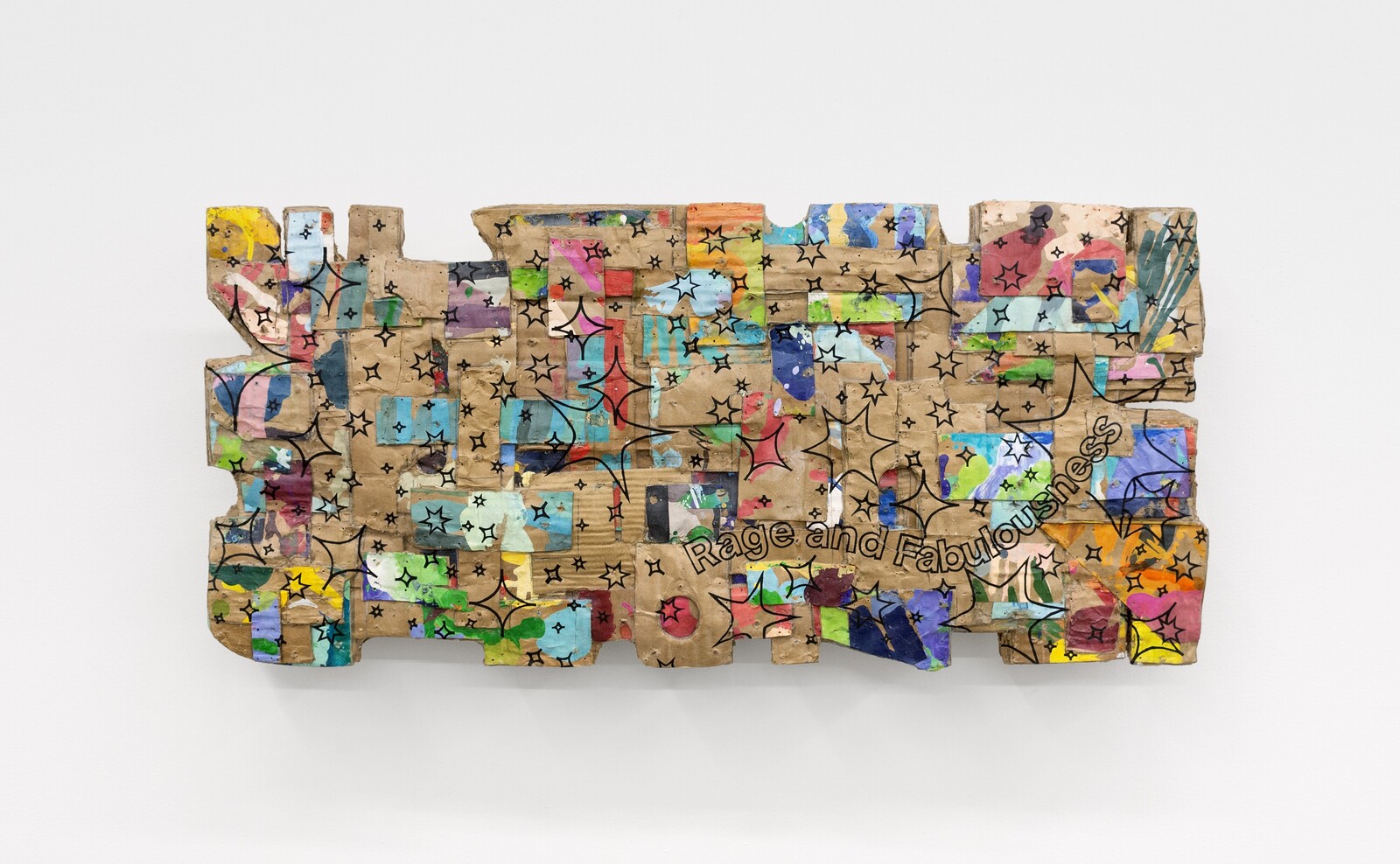

The paintings maintain a more ambiguous relationship to the video and, lacking simple pop-cultural slogans of the self, demand a little more work by the viewer. Never a bad thing. The series “Femme Trans-corporeal Fantasy”—acrylic on cardboard layered to variable thickness— consists of four paintings. Each is long and narrow, suggesting a full-length mirror (a nod to the location of the prom at the capital reflecting pool?), and covered in elaborate floral patterns that contain one relatively small femme figure. The troubled relationship between nature and gender is one subject of these paintings, the association between femininity and flowers returning our attention to the artifice of these ostensibly biological categories just as the recycled surface suggests the many ways these signifiers might be repurposed for meanings far from biological determinism.

Silvia Federici’s “Wages Against Housework” (1975), which is often misinterpreted as a call for something like a universal basic income, argued that women’s free reproductive labor in the home could only be recognized as work if it was paid for, that this was a precondition for organizing the reproductive labor of women, and that this organization for wages would precipitate the collapse of capitalism because, ultimately, capitalism could not survive the dissolution of the economic unit of the nuclear family and the free labor it entails. Even Karl Marx, not often celebrated for his feminism, noted that subsistence wages were actually sub-subsistence as they were effectively subsidized by unwaged household work. This work is not limited to middle and upper-class women who had voluntarily left the workforce.

One could object that anyone could theoretically do unwaged reproductive labor regardless of gender. What’s more, housewives seem about as far away from trans teenagers as one can get. The category itself seems politically dated, rightly coded as white and middle-class, and almost never a reality in an economy that demands at least two wages for subsistence. But proms are not about reality. They are about fantasies and normative ideals, and the ideal of heteronormativity is a smiling housewife. The housewife is the fantasy version of capitalism—where the unwaged labor of love that reproduces male workers is beautiful and conflict-free. As Federici and many feminists have pointed out, without heterosexual roles this free labor would not get done. It is under the guise of a biological mandate that women’s exploitation occurs—caring for a family is a labor of love, there is a natural connection between a mother and child, women are more equipped to do the emotional work of parenting and spousal support, etc. For all of these reasons, the suggestion of payment might seem absurd. But it is because women are not paid that these things are allowed to seem natural. In short, capitalism needs straight people. The homosexual threat was mitigated by the fact that it did not threaten the biological truths of binary gender system and it was, ultimately, neutralized through the heteronormative institution of marriage. The mere existence of trans people, however, upends the ideology masquerading as biology that subtends the whole operation.

Choosing a prom as a site of protest is therefore a far more threatening gesture than it appears at first glance. This is not simply an evening of enjoyment but the appropriation of ritual training in the heteronormativity that guarantees the future of capitalism. Proms, like weddings, are florid sites for denying the violence and exploitation that structures heterosexual relations. Anti-trans legislation is more than the irrational hatred of misguided religious fanatics. And the staging and defense of events such as a trans prom are far more politically important than many on both the left and right might want to admit.

The rights of the many trans people living in the United States have been characterized, as feminism once was, by many on the Marxist left as a distraction. Or, more cogently, as seeking recognition at the expense of a politics of redistribution. But fifty-four binders’ worth of legislation is too extreme a situation to dismiss. As Judith Butler has pointed out, the divisiveness that the left ascribes to sexual politics in general is reproduced in the very accusation of apostasy. And why, Butler asks, “would a movement concerned to criticize and transform the ways in which sexuality is socially regulated not be understood as central to the functioning of political economy?”1

The show’s virtues are many, but it might have been a stronger political statement if it had simply consisted of the devastating contrast between the massive collection of anti-trans legislation and the documentation of trans prom. This, however, is a problem of producing political work in the context of a commercial gallery, not a problem with the work itself or the politics of the artist, whose practice of collaborating with activists is truly admirable. Considered on their own, the paintings in particular are worth considerable critical attention, but the show as a whole seemed distracted from its political purpose by these extra objects. In the end this is less a complaint than a utopian sigh; yet another opportunity to confront how impossibly bound up we all are in the circuits of capitalism. I don’t actually believe that “Joy is an Act of Resistance,” but I do hold out hope that someday the terms will be different; already trans people have courageously offered us a glimpse of these new terms on an otherwise bleak horizon. Maybe non-commercial creative production will follow in their tulle- and sequin-covered wake.

Judith Butler, “Merely Cultural,” New Left Review (Jan/Feb 1998): https://newleftreview.org/issues/i227/articles/judith-butler-merely-cultural.