Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

June 21, 2021 – Review

Glasgow International

Rosanna Mclaughlin

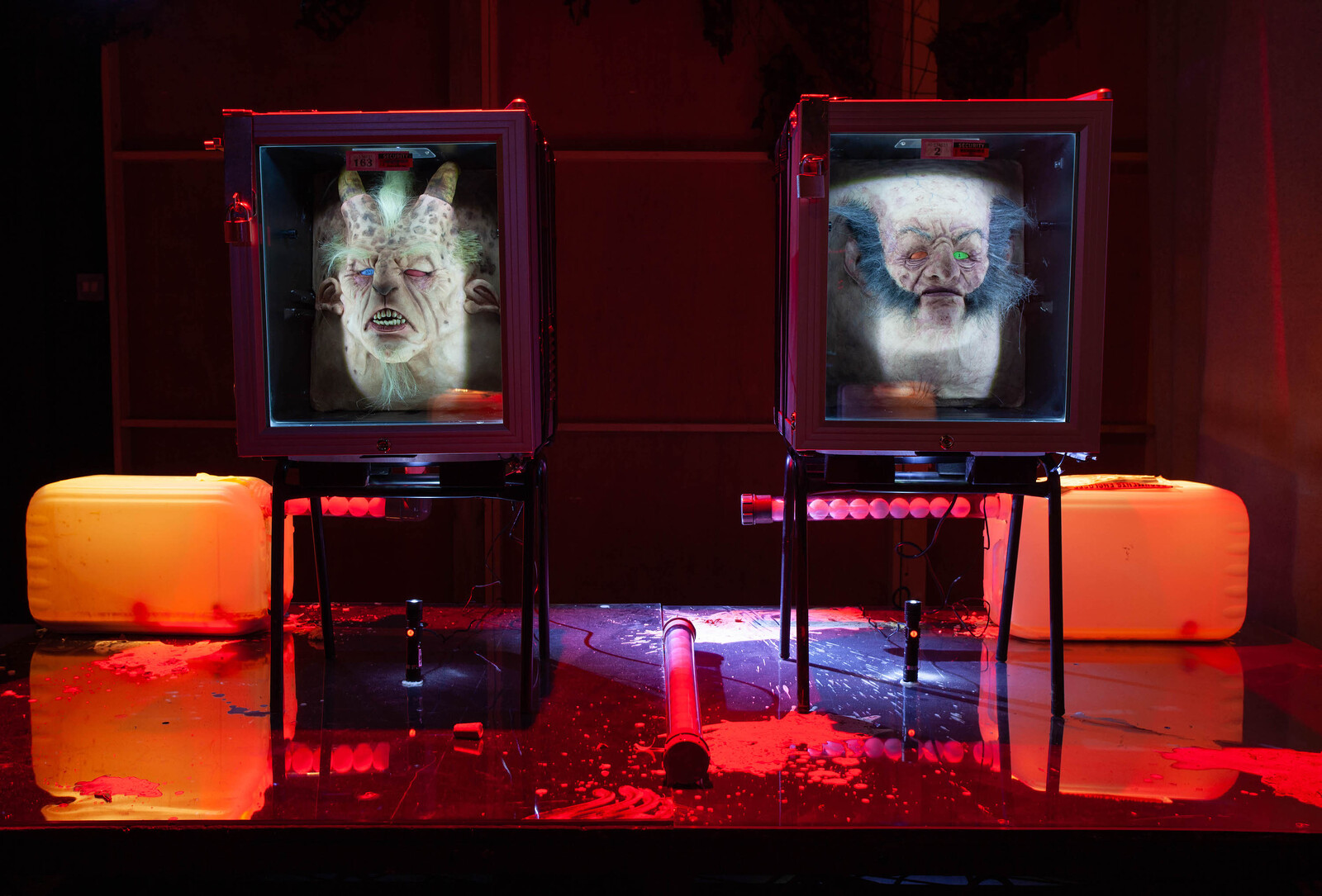

On my way to Tramway in Glasgow’s Southside I spot the artist Jenkin van Zyl walking past the McDonald’s on Pollokshaws Road. I know it’s van Zyl because I watched an online video about his make-up routine. He’s wearing prosthetic horns, hooks for hands, and nothing much on the bottom half, except for some strapping that reveals pretty much the whole of his arse. Van Zyl’s film Machines of Love (2020–21), showing at Tramway as part of Glasgow’s biennial arts festival, unfolds like a World of Warhammer cosplay fantasy with heavy shades of Paul McCarthy, in which a group of orc-like people with rat teeth and squashed noses conduct squalid sex games in an underground lair. The prosthetics are impressive, yet while van Zyl has understood the look, after 40 minutes of writhing around it’s less clear what he wants to say with it: a problem endemic in a culture that specializes in polishing and grafting pre-existing aesthetics.

The theme for this year’s festival is “attention.” During an era in which convoluted curatorial agendas have become de rigueur, director Richard Parry has opted for the opposite approach, picking one so open that you’d be hard pressed to find an artwork to …

December 12, 2019 – Review

Basma Alsharif’s “A Philistine”

Chris Sharratt

An ever-spiraling conflict, a splintered diasporic identity, the subjectivity of experience, the psychology of displacement: in the work of the Palestinian artist Basma Alsharif this heavy load is unpacked and sifted, as history and geography are questioned and clichés resisted. In her attempts to challenge didactic accounts of history and the misrepresentation they can engender, Alsharif often hits rewind. Moving backward in order to propel a narrative forward is a recurring motif in her lens-based work, a device she uses to powerful effect in her compelling 77-minute feature debut Ouroboros (2017), which opens with reversed drone footage of waves rolling away from the Gaza shore before panning back inland across the beach, a busy road, and city blocks.

In “A Philistine,” presented across three distinct gallery spaces at Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Arts, Alsharif plays with time in differing ways. A screening room with a two-seater sofa shows three looped short videos that bring the domestic and geopolitical together. In Further Than The Eye Can See (2012), the story begins with Alsharif’s grandmother’s arrival in Cairo after being exiled from Jerusalem in 1948 and ends with her birth in Jerusalem 11 years earlier. Told in English by a male narrator as …

February 8, 2019 – Review

Cécile B. Evans’s “Amos’ World”

Chris Sharratt

In the world of self-regarding architect Amos, there’s really only one thing that matters—Amos. There he is, sensibly chic in a black roll-neck sweater and neat gray trousers: “I want to build something important. I want to change the world. I want to express myself.” Amos is Cécile B. Evans’s amalgam of the twentieth-century starchitects who shaped the post-war built environment. Conceived as a mock TV series set in a Brutalist housing estate, her exhibition at Glasgow’s Tramway comprises three separate videos (or “episodes”). Made between 2017 and 2018 and collectively titled “Amos’ World,” each is screened concurrently in accompanying installations with soundtracks played on headphones. Dotted around the space are props and sets used on screen: scale-model shelves of colored binders, a miniature forest. As “Amos’ World” suggests, the egoistic visionaries Amos parodies were not ultimately in control of their designs. Evans emphasizes this point by rendering Amos as a jerky puppet.

Recent decades have seen the tearing down or repurposing of many of these architects’ buildings. Yet, Evans suggests, Amos has a far more influential contemporary equivalent in today’s social media monopolies and search engine monoliths—data architects whose mission is to “organize the world’s information” and …

December 14, 2017 – Review

“A Synchronology: The Contemporary and Other Times”

Tom Jeffreys

Flowers fade at different rates. In the November chill of a Glasgow art gallery, cut flowers—carefully arranged in a vase on the floor, their silhouette cast against the wall by the light from a projector—are taking their time to die, or to appear dead. (When exactly do cut flowers die?) At a certain moment of decay, a new vase will be selected from a nearby glass shelf, and a florist will arrange another bouquet, precisely styled to match the historical period of the vase that will contain it. This process has been set in motion by artist Corin Sworn and forms a work called Temporal Arrangements (2010). The vases come from Sworn’s own collection. The projector, I’m told, came from Yugoslavia—a country that no longer exists.

The multiple temporalities that Sworn’s work draws attention to form the irregular heartbeats of “A Synchronology,” a group show at Glasgow’s Hunterian Art Gallery. The exhibition, curated by art historian Dominic Paterson, is itself a temporal marker: it has been conceived to celebrate the tenth anniversary of The Common Guild, a Glasgow-based arts organization which runs a gallery in the city and commissions off-site projects including, in 2013, “Scotland + Venice” at the 55th Venice …

July 25, 2017 – Review

Martino Gamper’s “Middle Chair”

Francis McKee

The marriage of Italian designer Martino Gamper and Pollok House in Glasgow, set up by The Modern Institute, is a perfect match. Originally the ancestral home of the Stirling-Maxwell baronetcy, the house was built in 1752 and is run now by the National Trust as a public museum. Much of the furniture in the house today is not native to the site, having been imported by the Trust at various points in the history of the building.

All of this provides the ideal context for Martino Gamper’s intervention, which replaces several chairs in the house’s collection with his own unique designs (as well as providing chairs for invigilators and visitors). The unity of the house and its furniture has been disrupted over the years, and so the mongrelization of the interiors is echoed in the hybridity of chairs such as Fortezza (all works 2017) and Bobbin Ball. These draw on modernist design, but with elements collaged together from various periods and styles. Moreover, objects such as croquet mallets are absorbed into the furniture with a knowing wink towards the pastimes of mansion owners.

The surprise in this context lies in the peculiar mixture of aesthetic shock and familiarity. On one level Gamper’s …

April 13, 2016 – Review

Glasgow International

Kirsty Bell

That only 6 of the 75 locations numbered on Glasgow International’s essential city map are host to the “Director’s Programme” says something of the generous weave of the “official” and the “collateral” here, doing away with the two-tiered hierarchies usual in such events. Instead, a loose net is cast around existing public institutions, non-profit spaces in studio complexes, artist-run galleries, and commercial venues, with the odd special location thrown in. Though touted by the City Council as proof of Glasgow’s status as a “global leader in contemporary art,” director Sarah McCrory states that G.I.’s aim is rather to “highlight and support the activity that takes place throughout the year,” and to “focus on the important Glasgow-based artistic community.”

The center of gravity for this artistic community remains the Glasgow School of Art, so it was fitting that Thursday night’s opening party was held there, in the dark upstairs bar commandeered for the night by Marvin Gaye Chetwynd and the performance troupe MEGA HAMMER. Their endlessly morphing performance at times took to the stage but was more often ensconced amongst the audience members. A leotarded woman lying prostrate on her back gently prodded viewers with her two-meter-long pink prosthetic leg; cross-dressed waiters …

March 11, 2015 – Review

Jack Smith’s "Theater and Performance Works"

Francis McKee

Jack Smith (1932–1989) embodied a certain kind of New York—a chaotic, unpredictable, and unregulated city where creativity thrived amidst squalor and raw energy. Smith’s performances (from 1969 onwards) often took place in domestic spaces tipped towards catastrophe by his accretions of junk and debris, and by his regular assertions of his own failure. Reduced now to bare documentation, these performances are difficult to convey in their anarchic immediacy. The inevitable problems of exhibiting documentation are only enhanced by the clean, professional curation of contemporary galleries. Despite those hurdles, something shines through in this exhibition of documents related to Smith’s performance work. Perhaps Smith is just irrepressible, but the evidence presented in the drafts and fragments of his performance ephemera reveal more than might be expected.

The layout of the show anchors his work at either end of the gallery. Towards the entrance there is a large, luminous projection of Exotic Landlordism (1964–69) that blocks sight of the remainder of the works. The film has all the classic traits of a Jack Smith 16mm work, but in this context what is most important is the magnificent burst of color that confronts the eye. The sheer sensuality of the image bypasses rational consideration …

October 9, 2013 – Review

“Sea Salt and Cross Passes”

Jaclyn Arndt

Positioned like sentries on either side of the North Sea as it collides with the Atlantic Ocean, Norway and Scotland have long been held under the sway of this most frigid body of water. Crane-filled shipyards, woolen fisherman’s sweaters, mythical horned Viking helmets, and—as the exhibition “Sea Salt and Cross Passes” emphasizes—billowing canvas sails underpin both the mythic romance and gritty realities of these two nations. In her new memoir, The Faraway Nearby, writer Rebecca Solnit remarks that walking “into an exhibition can be like walking into the middle of a conversation that doesn’t make sense unless you know who’s talking and what was said earlier.” This is certainly true of this exhibition, which marks the first half of an exchange between two galleries, STANDARD (OSLO) and Glasgow’s The Modern Institute, and takes as its starting point the stretch of water that separates the two countries and informs both their cultures. The image of sails, so often captured in the maritime paintings that proliferate in seafaring nations, is what opens the exhibition’s conversation—and in particular, the diagonally sketched lines of masts attached to ships yawing off-center.

With its depiction of not only one, but three diagonal masts, Losbåten “Arendal 2”—an undated …