Far above the North Atlantic, a plane is flying from Venice to New York. Most of the passengers in business class sleep comfortably in their lie-flat seats, but one stays awake sipping complimentary champagne. His voice barely audible above the jets’ white noise, he muses: “Is there even any difference between biennials and contemporary art fairs?” The knee-jerk answer to his question would be, Of course. Biennials are typically organized by curatorial teams who engage in protracted research to stage thematic arguments. Whereas they ask their visitors to look and think, art fairs tell them to buy, or at least window-shop. Venice notwithstanding, most biennials exist in relatively peripheral locations and often target non-art audiences, while fairs are built to serve the needs of the global 1 percent who comprise their clientele. But another, more pertinent answer might be, Less and less, or even, Was there ever? As the sociologist Olav Velthuis has shown, aesthetic and commercial modes of exhibition have been indissociable throughout the history of the Venice Biennale. For its first 70 years, the Biennale had a sales office that worked on commission. Following the protests of 1968, it adopted new practices that spawned what Velthuis has called “the Venice effect,”1 wherein the putative independence of the Biennale comes to serve the needs of the market. The pretense of purity is often a smokescreen for covert business arrangements, even as it is belied by many artists’ dependence on dealers to finance their production costs. In a perverse but perfectly logical twist, the symbolic capital accrued by a biennial’s “autonomous” validation of an artist can readily be converted into increased exchange value.

More recently, the inverse of this dynamic has taken hold as prominent art fairs strive to resemble biennials. In what might be called “the Frieze effect,” fairs have increasingly incorporated discursive or participatory elements; they have also emphasized site-specific commissions and educational programs. The most obvious explanation for this shift is that it functions as a fig leaf, politely disguising the shameless promiscuity of the ever-tumescent contemporary art market. Yet as with biennials, the semblance of autonomy is a potent means of value production. Biennial-icity adds a veneer of intellectual sophistication, allowing work to be marketed as “critical.” It also allows a fair and its exhibitors to align their brands more strongly with the global contemporary, a now-ubiquitous category that invokes an abstract, near-empty universality. Given that this universality is in many ways indistinguishable from that of neoliberal capital, we might conceive of the global contemporary as a potent aesthetic ideology. Within this fantasmatic structure, the fair assuages its patrons’ fear of missing out even as it indulges their desire to discover (then flip) the next Oscar Murillo. The links between these imagined affinities and the conventions of pricing are at once indirect and indisputably real.

While the commercial success of Frieze New York is sometimes ascribed to the moribundity of its competition, it likely also derives from its canny application of the biennial formula. Though New York still fancies itself the center of the global art world, its connections to the biennial and fair circuit have been rather belated and indirect. Such conditions have surely increased the appeal of the Frieze brand, with its cosmopolitan, sophisticated connotations. The 2015 edition traded on this cachet by convening a team of international curators, a number of them with biennial experience. Not surprisingly, the majority of the fair’s more impressive offerings were in the stalls that had effectively been pre-curated. Shanghai’s Antenna Space exhibited a sharp suite of works by Liu Ding, “Karl Marx in 2013” (2014), one of which turned on the artist’s confrontation with Chinese tourists at Marx’s grave in London. Warsaw’s Le Guern Gallery showed compelling selections from C.T. Jasper’s photomontage series “In the Dust of the Stars” (2011). The Spotlight section, advised by Adriano Pedrosa, was a quiet revelation amidst the overweening vulgarity of the fair. Some of the artists shown there, like the marvelous Sudanese modernist Ibrahim El-Salahi, presented in London’s VIGO booth, have received major shows in Europe but remain largely unknown in the U.S. Others, like Geta Brătescu, whose drawings and collages were on view at Bucharest’s Ivan Gallery space, spoke to the formidable, largely uncharted range and depth of Eastern European conceptualisms. Such practices are still often treated as isolated curiosities despite their exposure to (and transformation of) Western models; one fascinating example of such an encounter was Natalia LL’s series of performance photos from 1977, “Natalia LL at LGBT Demonstration in New York,” shown by Warsaw’s lokal_30.

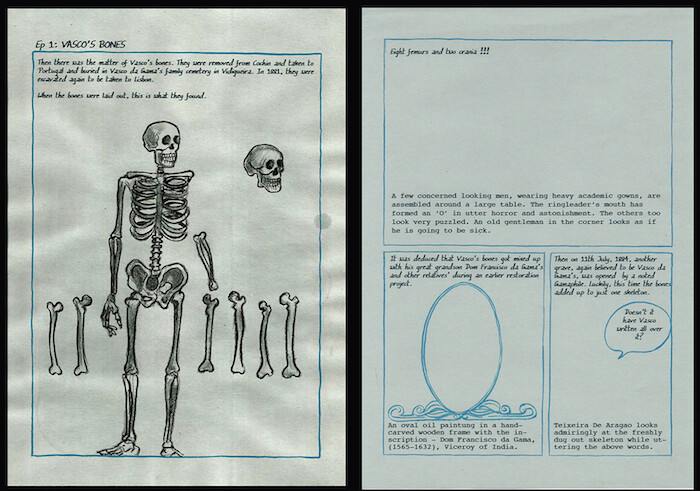

Elsewhere, and despite its more high-minded aspirations, Frieze New York is largely a crass spectacle of predictably conspicuous consumption. Finance bros in Gucci loafers rubbed shoulders with fashionistas, fashion victims, and the occasional celebrity; walking through the fair was a numbing, enervating experience rather like speed-reading the ads in Artforum. It became clear that “the global,” at least in this context, is a site of massive structural imbalance, even if exhibitors tended to revert to a much more superficial conception of global contemporary art: oversized photos of airport runways; displays of time-zone clocks; countless map collages and globe sculptures. Prominent displays were given to veterans of the biennial circuit, like Isaac Julien and Yinka Shonibare MBE; the most affecting was Allora & Calzadilla’s Intervals (2014) at Paris’s Galerie Chantal Crousel, which refashioned transparent plastic lecterns into odd plinths for dinosaur bones. Numerous galleries seemed intent on selling NYC-themed art to international buyers; the most diligent of these was New York’s Skarstedt, with iconic works by Warhol, Sherman, Holzer, and Haring, any of them perfect for your new luxury Tribeca pied-à-terre. With a fittingly gargantuan display of Richard Prince’s obnoxious Instagram paintings, Gagosian ventured the depressing proposition that global is just a fancy word for “lowest common denominator.” In fact the overwhelming majority of exhibitors were from the North, with hardly any from the MENASA region, Africa, or the Pacific. Those from the center could choose, though few did, to showcase their cosmopolitanism, as with Berlin’s Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, which brought works by Slavs and Tatars, Guan Xiao, and Katja Novitskova. In contrast, it was as if the galleries from the periphery were expected to showcase their own difference in a kind of compulsory self-exoticization. Athens’s The Breeder was outfitted with carpets, columns, and Byzantine-esque icons for Andreas Angelidakis’s Crash Pad (2015). Madrid- and Guadalajara-based Travesia Cuatro set itself up as a kind of tropicalist flower shop by Milena Muzquiz, complete with gallerinas in matching floral dresses. The one exception to this tendency was Mumbai’s Project 88, with Sarnath Banerjee’s “Liquid History of Vasco da Gama,” a group of 36 drawings by that incisively satirized Western stereotypes of postcolonial provincialism.

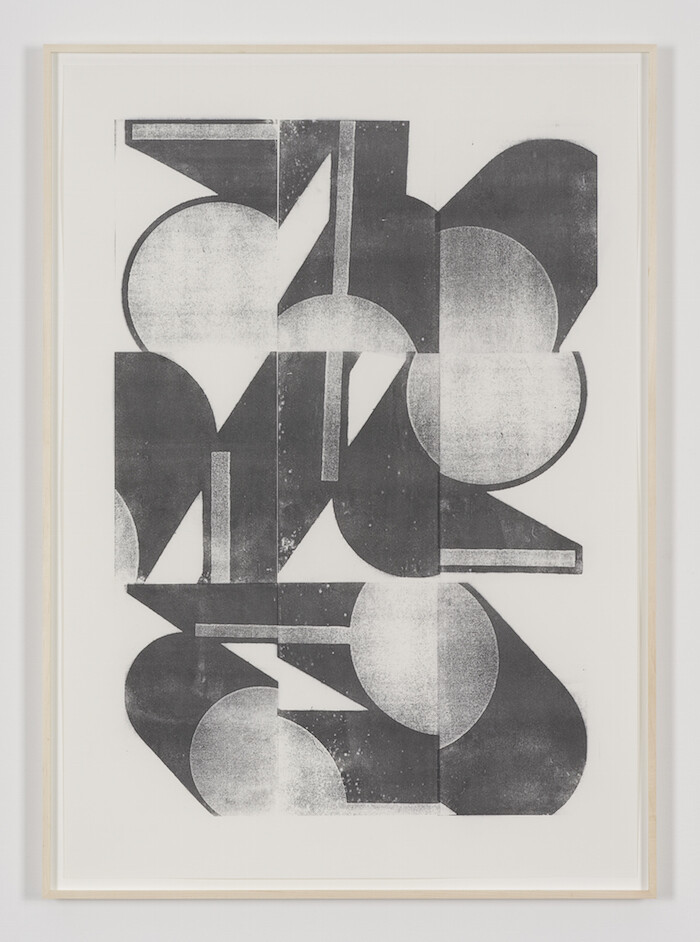

The few exhibitors who tried to resist this pervasive tendency did so by combining historically and geographically specific work with analogous contemporary practices. Paris’s Galerie Frank Elbaz assembled a stellar showcase of art from the former Yugoslavia, with memorable contributions from Josip Vanista, Mladen Stilinović, and Julije Knifer. Bogota-based Casas Riegner showed subtle, thoughtful contributions by Carlos Rojas, Bernardo Ortiz, and Johanna Calle. Berlin’s Galerija Gregor Podnar paired terrific, seldom-seen 1970s work from Ion Grigorescu, Irma Blank, and Goran Petercol, with strong recent pieces by Tobias Putrih and Anne Neukamp.

I left the fair with the impression of a massive embarrassment of riches, in both senses. On the one hand, it was possible to see more good art in a few hours than in a typical season in Chelsea. On the other, it was impossible to ignore the glaring contradictions of its very existence. These were perfectly encapsulated in the fair’s site: a multimillion-dollar bespoke tent with multiple VIP sanctums, located next to Icahn Stadium (named after the 1980s pioneer of corporate raiding, leveraged buyouts, and “asset stripping”) and just across the river from the South Bronx, home to the poorest congressional district in the U.S., where over 250,000 live in poverty. Inside this stylish white bubble, members of the global elite could be entertained by Amalia Pica, John Bock, and Geoffrey Hendricks’s reconstruction of George Maciunas’s Flux-Labyrinth (1976/2015), originally an attempt to develop an anti-capitalist aesthetics. Many eagerly lined up to participate in Wearing-watching (2015), a commissioned project by Pia Camil, in which they could don smocks modeled after Hélio Oiticica’s Parangolés from the 1960s (first designed in conjunction with residents of Rio de Janeiro’s Mangueira favela). Upon leaving the bubble, visitors were whisked back to lower Manhattan by a private water taxi. With the South Bronx quietly receding from view, they were free to ask themselves whether they had just been to a fair or a biennial, when and where the next big event might be, and whether such questions were even worth worrying about.

Olav Velthuis, “The Venice Effect,” The Art Newspaper Magazine (June 2011): 21-24.