“The missionary went on to talk about the Holy Trinity. At the end of it Okonkwo was fully convinced that the man was mad. He shrugged his shoulders and went away to tap his afternoon palm-wine.” So begins the tragic encounter between the fictional Igbo Chief Okonkwo and the religious men who are the harbingers of colonial power to his region of British Nigeria, as told in Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart (1958). The tale portrays, like no other, the foundational role of missionaries in statist imperialism. Here, the religious re-ordering of family, knowledge, and moral worlds is marked out as the true devastation of colonialism, enacting a destruction that exceeds that of imperial firepower.

It is just such a missionary figure that Dutch artist Renzo Martens has fashioned himself as over the past half-decade, most recently with his collective project the Institute for Human Activities, and the exhibition “A New Settlement” at Galerie Fons Welters in Amsterdam. Across six large chocolate sculptures, two small chocolate-sculpture editions, three videos, roughly a dozen photos, and other accoutrements, the “new message” of Martens’s “new settlement” is an evangelism of cultural capital. The claim is that gentrification—as the true product of art—may offer salvation from poverty in the so-called Global South.

Martens’s last major outing, Episode III: Enjoy Poverty (2008), saw the artist trudging through the Congolese jungle in a white linen shirt and local straw hat, striving to save the lumpen poor with the message that they must sell their own suffering through photographic means. Arguably the climax of the video is not the large neon “Enjoy Poverty” sign that Martens installs in a Congolese village, but an earlier scene in which Martens tips back his head and spontaneously sings out the lyrics to Neil Young’s 1972 song “A Man Needs a Maid.” This gesture discloses both the primary nature of Martens’s work as self-portraiture, as well as the bereft, Fitzcarraldo-like character he presents as an artist far from home and lonesome despite the plantation workers who walk alongside him.

According to the press release for “A New Settlement,” Martens’s disappointment that Enjoy Poverty had failed to produce concrete change among the communities it depicted inspired him to conceive an ambitious gentrification project titled the “Institute for Human Activities.” In the exhibition, the story of the project to date is told through a series of small photographs and videos in the entrance area, arranged in an installation resembling an office. Here we see the Institute’s foundation in 2012, with a small group of workers on a former Unilever plantation in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC); the abject working poverty in the area; and the happy collectivity of artistic production.

The choreography of materials within the office-like display is closely geared toward producing an itinerary of evidential claims. The images strain under their burden of proof, marshaled within Martens’s narrative of beneficent intervention. It is hard not to be sympathetic to this general impulse; that is, to forge a re-coupling between the viewers of contemporary art and those who are on the losing end of the capital that funds it, such as Unilever. And yet can an audience accept that the artist truly thinks that he will bring gentrification to an area where residents lack adequate sanitation, let alone telecommunication? Even if this seemed credible, one has to wonder when gentrification has ever worked to the betterment of the existing inhabitants of an area.

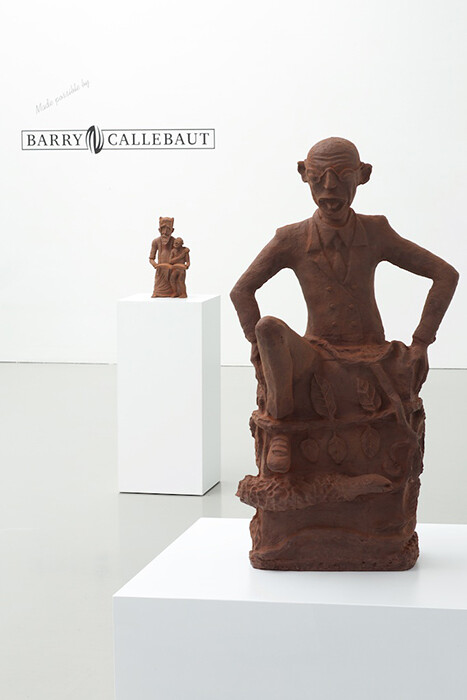

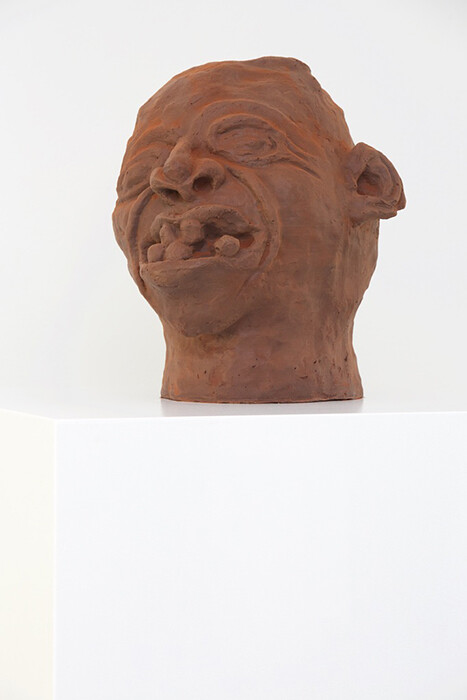

Instead, the impression across these perfunctory images is less of gentrification and more of an elaborate and extensively funded artisan enterprise project re-directed into the context of contemporary art. On a laptop screen, the short video Film about workshops and opening Artes Mundi 6 in Cardiff (2014) depicts the first presentation of the IHA’s labors at the Artes Mundi prize exhibition in Cardiff. The camera follows the fabrication of a series of figurative sculptures rendered in clay on location in the DRC then digitally scanned and re-created in chocolate. Six of these stand in the main gallery in Amsterdam as mirror presences of the video documentation. The largest sculptures, at slightly over a meter tall, appear as eerie and mythical figures, confronting viewers even before they enter the gallery with a dense and bitter odor.

The video ends with the presentation of a check for two thousand dollars, presented by Martens to the IHA workers and representing the total sales of the edition in Cardiff at 45 pounds each. Considering that the project’s supporters include the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent, Mondriaan Fonds, Amsterdam Fonds voor de Kunst, Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds, Prins Claus Fonds, and sponsorship by chocolatier Barry Callebaut, one again has to wonder what this profit margin means for the project as a viable proposition to emerge from a contemporary art context.

As with Martens’s earlier works, these images are ultimately directed toward producing change not so much on the ground as within audiences and discourses at the site of exhibition. Martens’s self-appointed mission, it would seem, is redemption—a term that binds together the economic and moral registers of debt. Appearing first in Exodus 21:8, redemption figures in the appropriate terms by which a man may sell his daughter into slavery and by which she may be freed: “if she please not her master, who hath betrothed her to himself, then shall he let her be redeemed.”

The moral codes of Christian scripture that secure humanity’s indebtedness to the divine are also found within the exhibition. Among the six large chocolate sculptures that stand in the rear gallery is Cedrick Tamasala’s How My Grandfather Survived (2015). The reddish-brown form depicts a bearded and robed elder with his arm over a young boy. Together they behold a book, inscribed with the biblical phrase, “Blessed are the poor.” The sculpture allegorizes the story of Tamasala’s grandfather who, as a young boy, was rescued from poverty by a Belgian missionary. The path to economic salvation was through a Western education that alienated the grandfather from language and kin. Perhaps the ultimate proposal of the IHA has little to do with the viewers and makers of these works, but rests with Martens himself—and whether this one man may ever experience redemption from his own share in that inheritance.