One of the biggest stories of the year in U.S. literary fiction was the publication of Garth Risk Hallberg’s debut novel City on Fire, for which the young author received a reported two-million-dollar advance––a startling number, even by the hyperinflationary standards of the contemporary art market. Such a bet seemed odd at first, given the novel’s length (nearly a thousand pages), complex plot structure, and setting (New York City in the bombed-out 1970s). However, on closer inspection the deal looked canny. With the commercial appeal of this period already proven by figures like Patti Smith and Rachel Kushner, what better time to roll out a novel full of potential screenplay material? (In the event, the film rights were optioned for six figures; the novel was also sold in 17 other countries.)

As this episode suggests, fistfuls of money are being made from the fantasy of being poor and beautiful and artisanal in New York. This is true not just in the U.S. but globally, where “Brooklyn” is the most recognizable brand identity for bourgeois-bohemian-hipster culture. One uncomfortable irony is that many of those who built Brooklyn™ can no longer afford to live there; another is that figures like Hallberg exhibit an impossible nostalgia for a time before they came of age, which in this case is also the moment just before Reagan-era neoliberalization initiated an extreme escalation of the city’s inequality.

An analogous relation between NYC hype, nostalgia, and the culture industry is operative in the current installment of “Greater New York,” the survey of local art held at MoMA PS1 every five years since 2000. Previous editions of the show have been chided for being too blingy, too presentist, and overly obsessed with market-driven trends. In response, this year’s curatorial team set out to compose a more restrained, retrospective edition, taking the term “greater” in a historical sense, as co-curator Douglas Crimp nicely puts it. These intentions manifest in the exhibition’s aversion to neo-formalist painting and post-internet art, and most refreshingly in the broad age profile of its contributors, over half of whom are 40 or older.

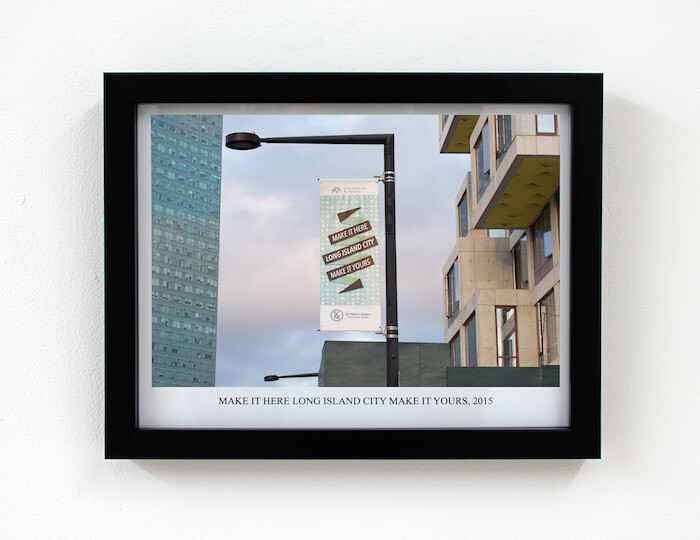

According to the curators, the recent exacerbation of the city’s social contradictions inspired them to seek out prior moments of comparable conflict. One emblem of this search is David Hammons’s still-trenchant African-American Flag (1990), which has been literally run up the flagpole of PS1 and is thus positioned squarely between a new condo development and the VW Dome. This unfortunate juxtaposition indicates something like a structural limit to the possibility of critique from within such an institutional context, and suggests that the success of “Greater New York” should be judged relative to its ability to analyze, dissolve, or somehow reframe such contradictions. Does the show uncover obscured links between New York’s culture and its politico-economic infrastructure, or does it recycle the sort of reified ideas that fuel the city’s myth-making machinery?

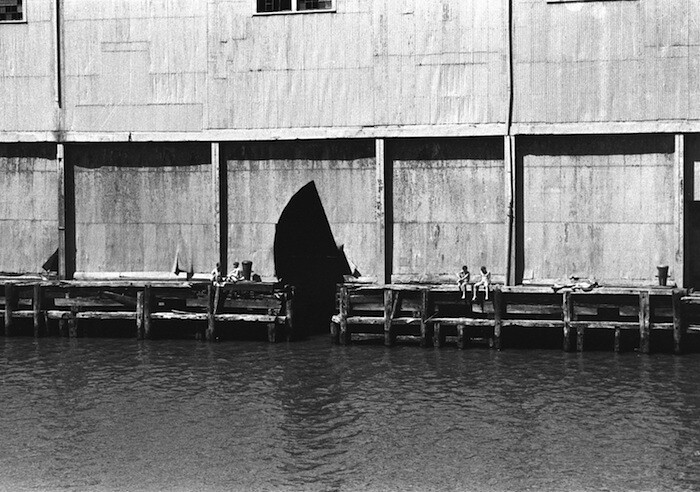

On balance, regrettably, the exhibition tends toward the second option, proposing a somewhat predictable and mediagenic narrative of the grittier, sexier, more authentic New York that supposedly existed before Williamsburg and Bloomberg. This account begins in the fabled 1970s with charismatic but familiar figures like Gordon Matta-Clark and Alvin Baltrop, who seized on the heterotopian lawlessness (and romantic decay) of the West Side piers. In a gesture that comes off as a bit disingenuous, the show includes works by several artists from PS1’s inaugural exhibition “Rooms” in 1976 (Matta-Clark, Richard Artschwager, Scott Burton, Howardena Pindell, and Judith Shea) without considering the complex ecology of independent spaces that gave rise to PS1 as an alternative institution that fervently opposed the establishment values of MoMA.

The story continues into the downtown 1980s underground, represented by Nelson Sullivan’s proto-reality TV tapes of scenesters like Lady Bunny; this picture might have been complicated by including the more oppositional work of Clayton Patterson, who took his camera into East Village squats and affordable housing rallies. It pauses to thoughtfully mourn the devastation wrought by the AIDS crisis, pairing a muted text installation by fierce pussy (For the Record, 2010/15) with a series of piercing monochromes by Donald Moffett (Blue NY, 1997). The curators pointedly acknowledge the 1990s with a showstopping display of figurative sculpture, recalling an earlier critical reaction to an abstract painting bubble. The show’s implicit narrative concludes with contemporary work that links the present to this larger history, as in Nick Relph’s large C-prints of new buildings under construction, photoshopped into Kodachromatic color to look prematurely aged (Untitled, 2004).

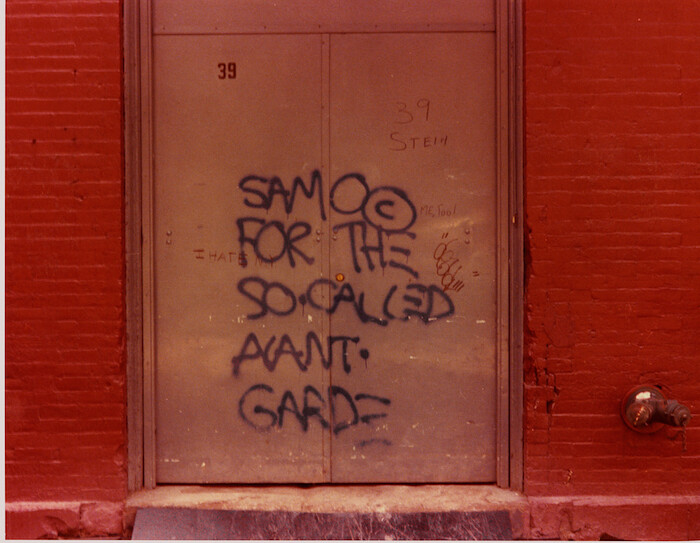

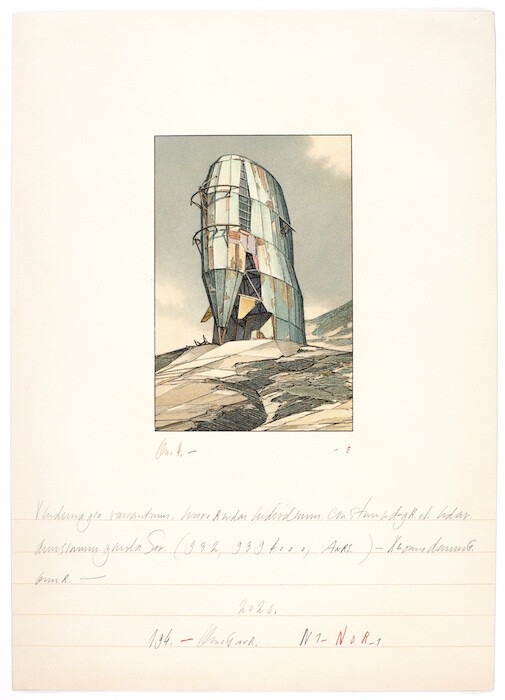

There are some pleasant surprises along the way, beginning with James Nares’s Pendulum (1976), a Super-8 film of an improvised wrecking ball swinging in a Tribeca alley, ominously marking the rhythm of “creative destruction” American-style. Seeing Henry Flynt’s photos of the SAMO© graffiti, gnomic slogans tagged across downtown parking lots and loading docks, is a reminder of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s linguistic genius; it also makes one wonder what might have happened had he pursued such collaborations further. A posthumous display of 1980s architectural drawings by Lebbeus Woods nearly steals the show, with torqued metastatic forms that cast urban space as a battleground between dystopian imagination and militarized reterritorialization.

That said, the exhibition contains too much art that represents New York overly literally, like Roy Colmer’s serial photography of doors, which resembles Martha Rosler’s Bowery series without the textual or conceptual mediation. Other material approaches the city figuratively, but in predictable or clichéd ways: examples include a throwaway work about clandestine sex by the otherwise dependable Lorna Simpson (The Fire Escape, 1995), or the neo-neo-Dada trash aesthetics of Stewart Uoo and Eric Mack.

Such is the influence of the New York culture industries that their presence is felt even when it is meant to be muted or negated, as in the massive sculpture gallery, filled as it is with objects and artists that rest comfortably within the prevailing market consensus. Here and elsewhere New York comes off as the capital of co-optation, a place where this month’s radical is next month’s chic. This dynamic is painfully clear in displays of putatively critical fashion by Eckhaus Latta and Slow and Steady Wins the Race, which are framed in weirdly dated references to deconstruction and postmodernism. A large gallery is given over to a recreation of the “curated” design pop-up KIOSK, a wonderful place to shop that gains nothing by being framed as art. Throughout the show are works by mid-career blue-chip artists like Gedi Sibony and Seth Price, whose art—and commercial success—depends on the rebranding of critically pre-approved strategies.

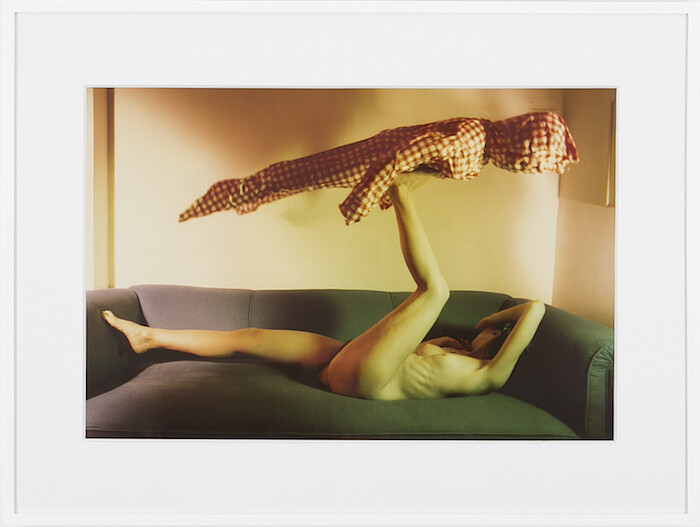

As these examples indicate, “Greater New York” largely falls back on established models in its search to make sense of the contemporary situation. The few exceptions to this tendency are where one senses an escape from the formidable inertia that comes with curating in a city like New York and for an institution like MoMA. Of the show’s lesser-known archival presentations, the two most powerful are the photographers Joy Episalla and Jimmy DeSana: Episalla with a series that figures the now-obsolete CRT TV screen as a semi-permeable membrane between public and private; DeSana with superbly twisted portraits that derive an uncanny frisson from props like soap suds, sweatshirts, and cellophane-wrapped toothpicks.

Among the younger artists the standouts are those who eschewed the dubious and so often sterile strategy of mating “criticality” to marketable forms. Ben Thorp Brown has contributed a wry, observant video documenting the manufacture of “deal toys” given as trophies to commemorate corporate acquisitions (Toymakers, 2014). Angie Keefer presents a suite of works whose price is tied to external fluctuations like real estate markets, or, brilliantly, her personal debt. In a series dealing with low-income neighborhoods, Cameron Rowland carefully links the abstract phenomena of neoliberal governance and securitization to such base materials as copper piping and the “pass-thru” devices used at bodega cash registers.

Despite the stated objectives of “Greater New York,” Rowland’s is one of only a couple of works to confront the fact that an astonishing number of New Yorkers—45 per cent, to cite one recent report—live in or near poverty. Another is Loretta Fahrenholz’s Ditch Plains (2013), a video documenting residents of neighborhoods devastated by Hurricane Sandy, who act out their situation in dark, coruscating dance-dramas that mix hip-hop athleticism, horror movies, and video games. In such moments one catches sight of a starkly different New York: a city that is not the one some claim to remember, one that is more damned and yet more resistant than some might care to think.