October 24, 2015–February 28, 2016

Puerto Rico’s art scene, which extends beyond the borders of San Juan to cities on the US mainland, has yet to be fully apprehended on its own terms. Perhaps this is due to the fact that Puerto Rico’s artistic production cannot be detached from its thorny political status vis-à-vis the United States—an Estado Libre Asociado (ELA) or Free Associated State—which is no more than a linguistic lubricant for colonialism and a chokehold for economic recuperation (the government owes its creditors an unprecedented 70 billion dollars and repayment is not a feasible option). At this historical juncture, the opening of the 4th San Juan Poly/Graphic Triennial: Latin America and the Caribbean provides a timely opportunity to examine how art, money, and politics feed off each other in one of the oldest colonies in the world.

Formerly the Bienal del Grabado Latinoamericano y del Caribe (1970–2002), the Poly/Graphic Triennial is organized by the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture (ICP), the cultural arm of the ELA. This year’s edition, curated by Gerardo Mosquera, Alexia Tala, and Vanessa Hernández Gracia under the title “Displaced Images / Images in Space,” “examines the expanded, instrumental, and decentralized nature of contemporary graphic arts and their development towards ‘post-graphics.’”1, eds. Vanessa Hernández Gracia, Gerardo Mosquera, and Alexia Tala (San Juan: Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, 2015), 3.] The concept of displacement operates as the exhibition’s main axis, taking as a point of departure the transfer of ink between plate and support in traditional printmaking. Yet, despite the Triennial’s emphasis on the expanded concept of “poly/graphic” (and now “post-graphic”), medium-specificity still functions like a curatorial straightjacket, restraining and prescribing subjects that could otherwise respond to, and engage with, the urgent conditions of the current local context.

One of this Triennial’s most salient aspects is the extension of “poly” to the structure of the event itself, which sprawls over nine institutions throughout the island. However, Puerto Rico’s unstable institutional politics led to delays in both the production and shipping of works, which left galleries empty and held-up openings. Initially, it would seem that the Triennial’s structural and bureaucratic problems overshadow the works on display. But more than that, the inability to see the Triennial in one venue—plus the distance between exhibitions—contributes to the sense of dispersion and fragmentation that permeates this year’s event.

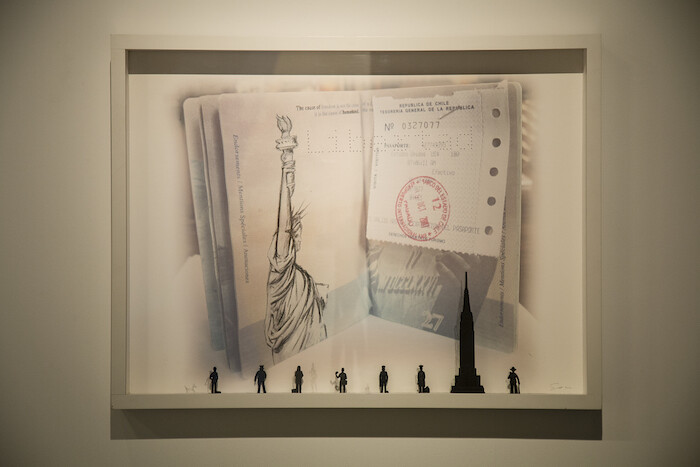

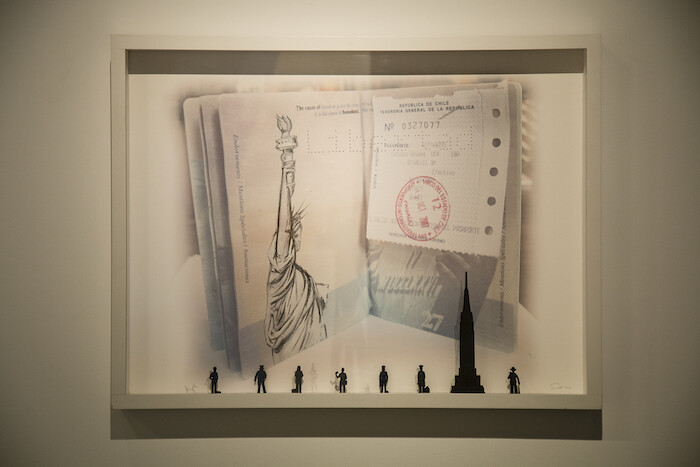

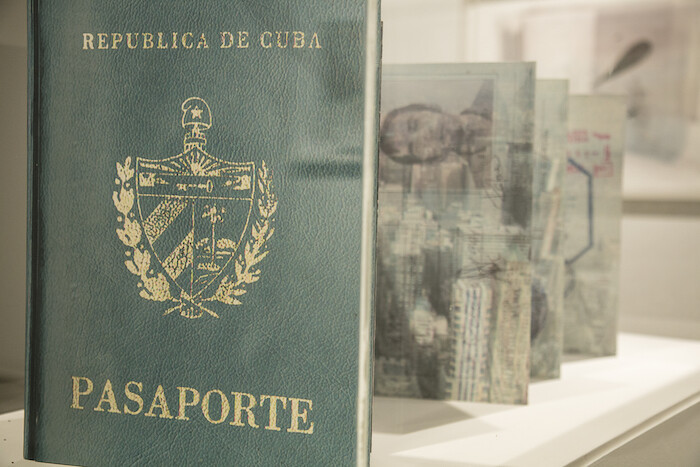

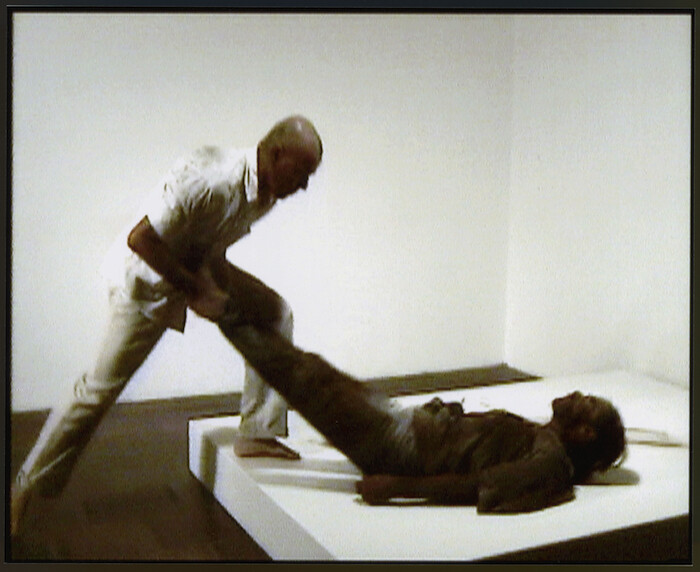

The main venue of the Triennial, the Antiguo Arsenal de la Marina Española, opened to a protest staged by ICP union workers whose payment of a summer bonus under union agreements was not fulfilled, while government funds continue to sustain the Triennial (transportation of works in the Triennial, for example, allegedly cost the government half a million dollars alone). Inside, in a series of mixed-media collages under the title Travel under the American Dream (2012), Cuban artist Sandra Ramos uses patriotic imagery sourced from Cuban and US passports belonging to her friends to point to the contradictions between America’s purported democratic ideals and the sordid reality of immigration. In Mugre (1999–2000), a powerful and controversial performance documented on video, Colombian artist Rosemberg Sandoval uses the body of a homeless man he picks up on the street as a tool to stain a white cube gallery space in Cali before then returning him to the streets. Somewhere between social criticism and exploitation, Mugre evidences that condemning social oppression and marginalization by reproducing its logic can be a tricky artistic feat. At Museo Casa Blanca, Fernando Bryce’s Posguerra Perú (2013) is a forceful installation of framed ink drawings that mimetically reproduces pages culled from different news sources from the artist’s native Peru between 1945 and 1948. The juxtaposition of news, propaganda, and advertisement reveal the political and ideological fissures of official histories through memory. Although these and other works in the Arsenal deal with displacement in a political and social sense, their political content is seemingly neutralized under a rubric of medium-specificity, in this case printmaking: ironically, it’s a medium that historically has been used on the island as an ideological tool of the state.2

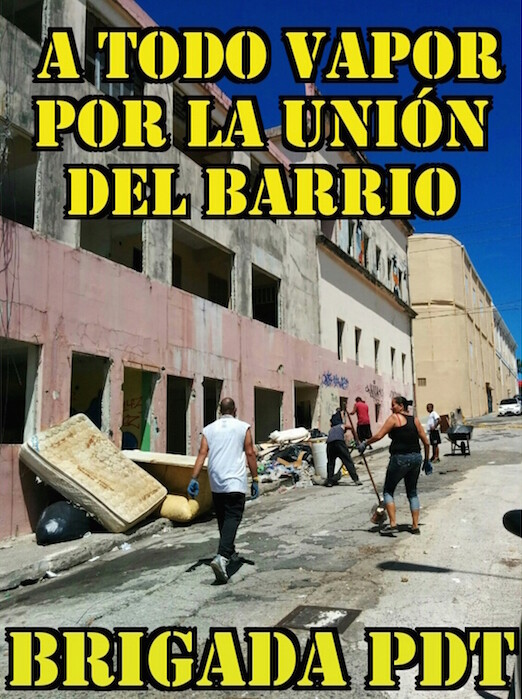

Some of the Triennial’s most interesting projects are happening on the margins of its official structures. A case in point is a project instigated by San Juan artist Jesus “Bubu” Negrón with the residents of Puerta de Tierra, a former maroon settlement and a marginalized working-class neighborhood that has recently been gentrified, and where Negrón has been living for the past seven years. Negrón used his assigned budget to continue his work with the grassroots community organization Puerta de Tierra Brigade, hiring residents to recuperate a derelict building-turned-crack den for the use of the locals, an inherently political gesture, considering that the island is being sold piecemeal to foreign investors.

Beyond the Triennial, the Caguas Art Museum presents “Sucio Difícil,” an exhibition of experimental works and documents by artist, musician, and curator Nelson Rivera. In the sound piece queremos a carlos romero barceló [we want carlos romero barceló] (1979), Rivera repeats to the point of annulation the political slogan of Carlos Romero Barceló, a former pro-statehood governor infamous for corruption and state-sanctioned violence. While being repeated, the sentence is gradually transformed into queremos sacarlo [we want to take him out]. Repetition, in this case, becomes a tool for change and emancipation.

In the southwest part of the island, between the municipalities of Guayanilla and Peñuelas, Puerto Rican Light (Cueva Vientos) (2015), a new work by Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla, will be on view for the next two years, supported by Dia Art Foundation and Para la Naturaleza, a not-for-profit organization of the Conservation Trust of Puerto Rico. The project consists of the installation of Dan Flavin’s 1965 sculpture Puerto Rican Light (to Jeanie Blake) inside a natural cave. The sculpture, composed of three differently colored neons, is charged with a solar-charging battery pack located outside the cave (and therefore powered by Puerto Rican light). After a fifteen-minute hike across a tropical rainforest, visitors can find Flavin’s work encased in a temperature-controlled glass casing: a relic/shrine to Minimalism, or a metaphoric subversion of Puerto Rico’s dependency on the United States? Whatever might be the case, the installation of Flavin’s piece at this site could also easily be interpreted by local audiences as a colonial gesture staged for the transnational elite of contemporary art.

Back in San Juan, Tito Rovira, owner of the gallery Roberto Paradise, just opened a tiny project space in his apartment. As its name suggests, “Maid’s Quarters” occupies the private living space of hired help, and measuring six feet by six feet, it is probably the smallest exhibition space in Puerto Rico. For the opening, Rovira presented works on paper by José Lerma, Richard Hull, Walter Sutin, and Mario Ybarra Jr. Meanwhile, at Rovira’s main gallery in Santurce, he showed large-format interactive sculptures by the artist collective Poncili Creación made with found wood and foam, forming colorful, surreal scenes.

At artist-run space Embajada, “Mapas del Cerro” by Chemi Rosado-Seijo features works made with accumulated layers of old paint scraped from houses at El Cerro, a poor community with whom Rosado-Seijo has been working with for over ten years. Embajada also hosts The Chagos Embassy of Puerto Rico, a conceptual project curated by Paula Naughton that establishes a symbolic diplomatic space between The Chagos Islands and Puerto Rico, two island-nations under colonial rule. Presenting paintings by Chagossian artist Clement Siatous that depict regional scenes, the project makes visible the history of the Islands as well as the current Chagossian diaspora, whose members have remained stateless after their deportation by the British Government in the 1970s to make way for a US military base.

Now that most works have reached the Triennial and all its venues have opened, one wonders about the function (if any) of this type of event. Should an exhibition bring respite to an otherwise depleted economic and political landscape, conceiving of itself as a modern utopic space, or should it more explicitly address the local context? While the successes of this year’s edition are many—notably the inclusion of works never seen before on the island, the generation of numerous parallel events, and an unprecedented educational program—the format begs for further reconfiguration. In its current layout, the Triennial doesn’t aspire to any social agency, instead opting to operate comfortably in the symbolic sphere. In Puerto Rico, as the ELA continues to collapse and its partner institutions follow suit, a Triennial that is disconnected from its locality and is instead focused on international models and cultural tourism is simply bound to reproduce the mechanisms of colonialism.

Gerardo Mosquera in 4th San Juan Poly/Graphic Triennial: Latin America and the Caribbean [exh. cat

In the late 1940s, under Luis Muñoz Marín (the author of the ELA), the government created the Division of Community Education (DivEDco), an initiative that hired local artists, in particular printmakers and filmmakers, to make posters, films, and printed material to further the government’s ideological agenda regarding culture and nation.