Whatever one might think of Ai Weiwei, he has made it impossible to simply not think about him. Ai’s will-to-notoriety has led to him to become all but ubiquitous, with much of this publicity deriving from his transformation into the world’s most prominent artist-activist. Critical reactions to this development have been mixed. While some have hailed Ai’s bravery, taking this reinvention as a convincingly artistic act of self-fashioning, many have criticized him as a sloppy artist, an opportunistic activist, or an impresario who forces both art and politics into the service of his own self-promotion. Still others have sought to split the difference: “wonderful dissident, terrible artist,” as Jed Perl put it in the New Republic.1

It is difficult to find adequate precedents or analogies for the position of Global Artist-Activist that Ai has created for himself. Andy Warhol shunned politics, whereas Joseph Beuys wanted little to do with pop culture; in some ways Ai’s aesthetic and commitments resemble those of Thomas Hirschhorn and Tania Bruguera, but neither enjoy anything like his degree of international exposure. It would seem that the best parallel is the celebrity humanitarianism of Angelina Jolie or Bono: the artist has made publicized visits to refugee camps; produced work at Fukushima; and staged actions in the U.K., Germany, the Czech Republic, Denmark, and Greece in response to the Syrian refugee crisis, as well as a widely derided photograph in which he re-enacted the image of the drowned boy Aylan Kurdi. He has collected awards from Amnesty International and the Human Rights Foundation, while a recent show at Alcatraz featured Lego portraits of 175 prisoners of conscience, including Nelson Mandela and Edward Snowden; in such a context Ai’s own “soft detention” in China hardly needed to be referenced. No matter how one judges such activities, they clearly can’t be written off as mere dilettantism.

His ascent to the global stage might be dated to 2008, the year that Ai’s Bird’s Nest stadium hosted the Beijing Olympics but also the year of the devastating Sichuan earthquake, to which Ai responded by shooting documentaries, archiving remembrances of those lost, and helping to organize Citizen’s Investigations. He also produced one of his most powerful works to date: Straight (2008–12), a massive, haunting installation comprised of 150 tons of rebar salvaged from quake debris and straightened by hand. In part because of these challenges to the state’s authority and moral legitimacy, Ai was made the target of continual harassment, and became a cause célèbre in the Western art world, most memorably in the RELEASE AI WEIWEI display on the exterior of London’s Tate Modern during Spring 2011. An HBO miniseries, following on the heels of the two documentaries (Ai Weiwei: The Fake Case, 2013 and Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, 2012) currently available on Netflix, can’t be far off.

Such a combination of high-culture credibility and middlebrow viewability is a prize for the parts of the culture industry that don’t like to think of themselves in such vulgar terms. It’s no surprise then that the current season in New York features four Ai Weiwei exhibitions, distinct but overlapping, at three different galleries (Deitch Projects, Lisson Gallery, and the Chelsea and Midtown branches of Mary Boone Gallery). These shows follow on the heels of the travelling retrospective “Ai Weiwei: According to What?,” which visited the Brooklyn Museum in 2014, and they anticipate a high-profile collaborative installation with Herzog & de Meuron, which will take over the Park Avenue Armory next summer. This sort of cross-platform synergy resembles a marketing campaign or the coordinated rollout of a presidential candidate. While it could well be that Ai is leveraging his notoriety and market position to support his activism, this doesn’t mean that his art (or his self-promotion) should remain immune from judgment.

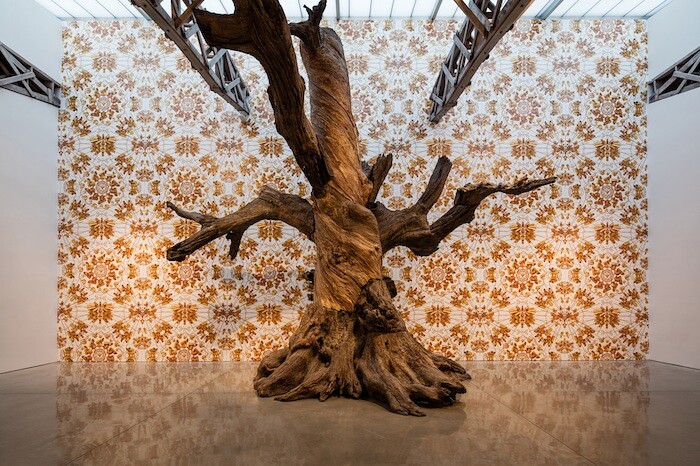

The most surprising thing about the shows is how dull they are, at least those at Mary Boone and Lisson, which are joined by the common title “2016: Roots and Branches.” While the three installations are staged as impressively and immaculately as one would expect, they are also emblematic of the uncharacteristically risk-averse form that Ai’s more overtly commercial work can take. Whereas the artist once shunned the mainstream Western market, he has apparently made his peace with it, adapting himself to these surroundings without much protest. The guiding principle seems to be moderation: there are enough recognizably “Chinese” elements (porcelain teapot spouts, reclaimed wood from rural China) to make his work appear culturally specific and thus semi-exotic, but not so many that it reads as unmodern or folkloric. The formal strategies (installation, appropriation, conceptualism) are current enough to read as contemporary, but have enough art historical pedigree to be a safe investment. Politics recedes into the background; in what seems like an inadvertent or at best callous irony, it is literally reduced to wallpaper (bespoke, with a refugee camp theme) at Lisson.

It is only in the Deitch Projects show, “Laundromat,” that Ai’s artist-activist commitments are fully on display. The personal belongings and photographic documentation that comprise the exhibition were sourced during a visit to a refugee camp near the EU border between Greece and Macedonia. Unlike a similar earlier project, which incorporated drawings made by refugees in Iraq, “Laundromat” didn’t allow its subjects any form of active self-representation. Instead, it evoked their experience only through the soiled shoes and clothing left behind. Ai and his studio carefully cleaned these items before displaying them en masse, a gesture meant to dignify their original owners, although one that inevitably recalls the self-mortifying cleaning rituals of Christian saints even as it slyly echoes the familiar American institution of the Chinese laundry.

Although Ai tends to overuse the numerical sublime, in this case the display of so many items poignantly gestured toward the scale and the human impact of the ongoing catastrophe in the Middle East. As in similar 1990s-era installations by artists like Christian Boltanski—displays which have since been incorporated into the visual rhetoric of Holocaust museums—the viewer is painfully reminded that each pair of shoes belonged to someone who is or was somebody’s child. This realization can generate enormous pathos, but it is also perilously close to kitsch. At Deitch Projects, Ai achieves a moment of genuinely devastating feeling, one which lasts for a long beat but is soon overcome by a sense of ickiness. Any doubts are quickly settled by the exhibition’s other components, which include wallpaper made from camp photographs and a video that ends on a shot of a girl’s sneaker with a blinking heart-shaped light. At that point it becomes disappointingly clear that the show isn’t going to change what one thinks or how one feels about the refugee crisis; the only question is what sort of kitsch it is and whether such a question might tell us something interesting.

In many respects “Laundromat” conforms to received definitions of kitsch. It caters to familiar expectations and is easily consumed; it aims to produce simple effects (here, a kind of pity or sympathy that is closely informed by liberal bourgeois guilt and narcissism); it is constructed according to academic or institutionalized formulas. Like many of Ai’s other installations, it relies on a relatively literal conceptualism. This is in part because the artist means to address an international, non-specialist audience, but while this is an important intention—the very possibility of Global Activist Art depends on such a means of address—in practice it tends to result in work whose “message” is easily deduced, with little left besides. “Laundromat” loudly asserts its own quasi-heroic moral importance while staggering under the weight of a common contradiction: namely that the more such art proclaims itself to be radical and urgent, the more it reveals itself to be conventional and boring. This lack of complexity is evident not just in the form of the work, but in the tasks it sets for itself. Despite Ai’s admirable bravery in the face of Chinese state repression, too little of the art he has made since his release takes aesthetic risks or asks difficult questions.

Such compromises suggest that Ai’s recent transnational reorientation has achieved the dubious distinction of pioneering a new form of humanitarian kitsch, one best encapsulated in the Aylan Kurdi photograph. In understandably but carelessly assuming a universal audience, this kind of art fails to recognize that the effectiveness of artistic engagement turns on how it negotiates the ethics and politics of representation, in all the senses of this highly overdetermined term. Taking Ai’s response to the refugee crisis as an example, it would seem that his sense of urgency has led him to produce highly topical but ultimately shallow work: to cover Berlin’s Konzerthaus in life jackets, as he did in February, portrays refugees as voiceless, generic victims while failing to grasp that few Germans, least of all Berliners, need to be reminded of the refugee crisis. In the case of “Laundromat,” Ai’s installation failed to register the apparent legitimation of xenophobia in Donald Trump’s electoral victory, or the United States’ contemptible apathy toward those displaced by its wars of aggression; it was no more aware of the housing crisis engulfing Manhattan’s Chinatown, a short walk from Deitch Projects. Without a close attunement to how artists, subjects, and publics are mutually entangled, art has little hope of identifying, much less contesting, the underlying conditions of possibility that constitute the political.

Jed Perl, “Noble and Ignoble,” the New Republic (June 2013), https://newrepublic.com/article/112218/ai-wei-wei-wonderful-dissident-terrible-artist