The phrase “make-believe media” was coined by Michael Parenti in 1991 to describe how the United States’ entertainment industries reproduce myths that justify the unequal distribution of power. The racism, militarism, and misogyny coded into pop cultural forms like the television drama, he proposed, do not reflect social realities so much as prefabricate them. The term is useful in the context of “Myths of the Marble,” an ambitious group show exploring ideas of the virtual, because it implies that “make-believe” does not merely connote “fictional” or “unreal” but also describes a function of uncritical culture: to make its audience believe in the grand narratives, from American exceptionalism to white supremacy, by which social differences are legitimated. Curated by Henie Onstad’s Milena Høgsberg and Alex Klein of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia (where it runs April 28–August 2), the exhibition suggests that prior to changing the world, it is necessary to “make-believe” new versions of it.

In the literary tradition, alternative realities are typically accessed via a portal and navigated with the help of a guide. Screened on a monitor in the exhibition’s second room, Chris Marker’s digital animation Ouvroir, the Movie (2010) consists of a tour through the “virtual museum” constructed by the artist in Second Life. As in Wonderland, your companion through this topsy-turvy world of inverted logics and irrational architectures is a disincarnate Cheshire Cat. He takes you through a winding picture gallery in which the canon of Western painting is defaced (or augmented) by witty digital collages: Icarus replaced in Bruegel’s famous disaster painting by the Challenger space shuttle; the protagonists of Manet’s Dêjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) reimagined as online voyeurs. At the tour’s conclusion, this trickster figure recounts an anecdote about a witness to the Battle of Waterloo who “knew he was watching the end of a world.” This is one of those crises that cause a historical moment—a fabricated reality—to become conscious of its own status as such. Marker’s feline avatar gestures through the screen to ask, prophetically, “What are you watching?”

Stationed near the beginning of an exhibition which takes the form of eleven more-or-less discrete solo presentations along a fixed route, Marker might be understood as a guide through its various worlds and as a pioneer in whose footsteps a younger generation of artists should follow. Shahryar Nashat’s Present Sore (2016) is among the works to share Marker’s antipathy to the realist mode (and the reality it claims limpidly to depict). Exhibited on a freestanding LED screen of roughly human dimensions, the video cuts rapidly between dismembered details of a composite body and prosthetic objects including clothes, medicines, lubricants, and artificial limbs. This fragmentary portrait is interrupted by an unsettling dream sequence featuring Paul Thek’s Hippopotamus from Technological Reliquaries (1965), a slab of flesh that the artist exhibited in a vitrine to provoke associations with the Vietnam War. In the context of Nashat’s work, it prompts reflection on the jarring disconnect between the techno-utopian discourse surrounding prosthetics—the enablers of an extended “posthuman” reality for the wealthiest citizens of the west—and the violence inflicted every day on vulnerable bodies elsewhere to prop up the systems that enrich that elite. As with Marker’s politically engaged cinema, formalist strategies serve to jolt the audience into an awareness of realities from which they are insulated.

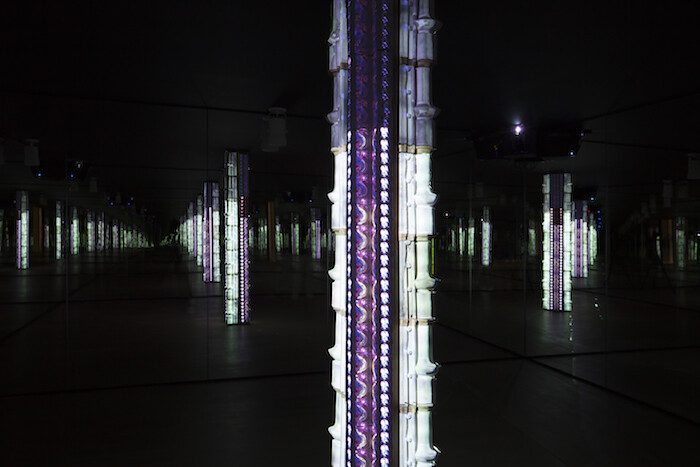

Nashat’s work undermines the myth of indivisible selfhood that finds its most enduring expression, in art historical terms, in the medium of marble. Michelangelo’s assertion that “the sculptor arrives at his end by taking away what is superfluous”1 supports the classical (and modernist) convention that beauty, and by extension truth, is synonymous with pure forms and material integrity. This essentialism might explain the general distaste for the museological process of “infilling”—by which marble statues are reconstructed from an original fragment—which provides the literal and theoretical foundation for Cayetano Ferrer’s Endless Columns (Chicago School) (2017). As Nashat’s video revolves around a disembodied art historical artifact, so Ferrer’s six-foot-tall cross between a computer mainframe and a spinal column is built out of two architectural fragments in the American revivalist style. With this hybrid aesthetic, Ferrer suggests that the essentialist myths embodied in classical marble sculpture might be replaced by values of mutual dependence, historical appropriation, and cyborgism.

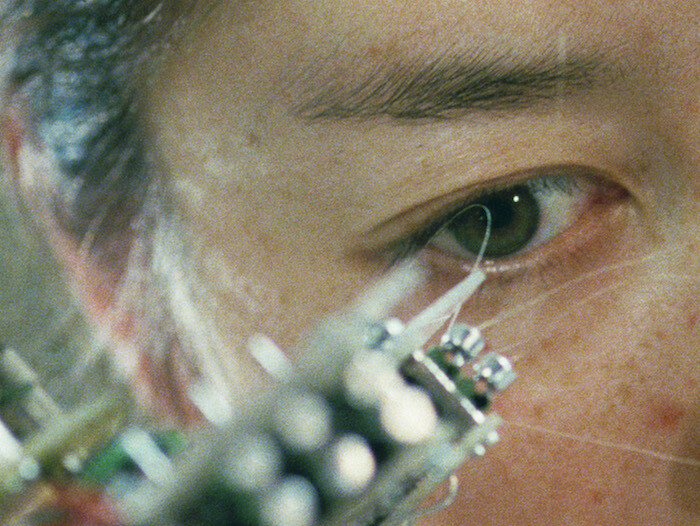

The possibility of coalition between human and nonhuman actors is a recurring theme in the exhibition. Daria Martin’s Soft Materials (2004) presents a series of intimate pas de deux between naked dancers and robots which tentatively learn from, and respond to, their movement and touch. By positing embodied play as the site of meaningful collaboration between species, the 16mm film works against the pernicious assumption that “progress” consists in the gradual migration of the material world into the virtual. That lesson is reiterated by Susanne M. Winterling’s mixed media investigation Glistening Troubles (2017). Charting the bioluminescent pyrrophyta (literally, “fire algae”) which alert Caribbean fishermen to atmospheric change, the work offers a timely reminder that humans collaborated with alien intelligences long before the invention of binary systems. More pressingly, it suggests that the new frontiers being opened up by digital technology do not compensate for the catastrophic extinction of nonwestern and indigenous systems of knowledge that is characteristic of our age.

The inextricable entanglement of real and virtual, nature and culture (or “natureculture”) is also addressed by Ane Graff’s What Oscillates (2017). This installation presents the rare earth minerals that contain the elements upon which our digital devices depend as sculptural objects on glass plates supported by a delicate hanging steel structure, like a cabinet of geological curiosities. The work exhibits a flair for the arrangement of disparate materials, but the daintiness of the installation risks reproducing the metaphors that it ostensibly critiques: of weightlessness, ethereality, abstraction. While the subject of this work draws attention to the ecological and human impacts of extracting these materials, its form denies it.2

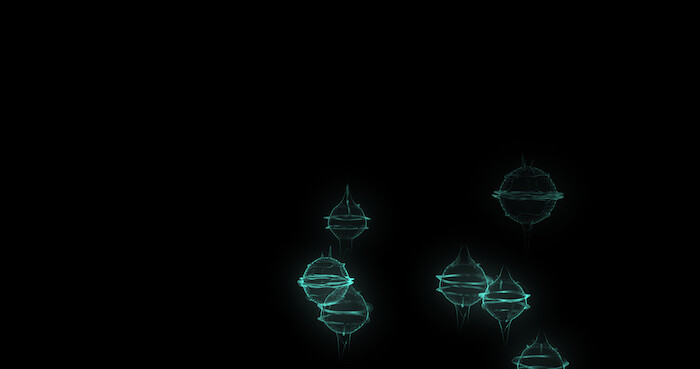

The exploitation concealed by myths of immateriality is dramatized in Sondra Perry’s IN THE GAME ‘17 or Mirror Gag for Vitrine and Projection (2017). This room-sized installation, centered on an HD video and animation, takes as its point of departure the experience of the artist’s brother. As a college basketball player, his likeness was—in common with tens of thousands of other, predominantly black, athletes—transformed into an avatar for use in lucrative sports video games. Filmed playing the game in which he unknowingly featured, Perry’s brother scrolls through a series of “players” whose physical characteristics identify them as his ex-teammates. One by one, he restores to these anonymous simulacra the names and histories of the individuals they reproduce. Perry’s work shows how bodies are transformed into the raw material for virtual economic systems from whose profit they are alienated.

Speaking at a symposium on the opening weekend of the exhibition, Perry drew attention to Sun Ra’s observation in 1971 that “black folks need a mythocracy not a democracy” because the “truth is not permissible for them to use.”3 The implication is that the existing versions of history and truth—and the systems of government they support—are realities which do not accord with the lived experience of black people, and from which they find themselves violently excluded. Rather than a radical relativism, the “mythocracy” that Sun Ra proposes is a “make-believe” version of reality that does not diverge from the experience of those excluded from power but more faithfully corresponds to it. In these unreal times, that is the task of the artist.

Often and illuminatingly misquoted as “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” Michelangelo’s letter to Benedetto Varchi, reprinted in Richard Duppa, M. Quatremère de Quincy, The Lives and Works of Michelangelo and Raphael (London: Bell & Dandy, 1872), 151.

For details on the “very high environmental costs” of rare earth mining, and the rush to exploit deposits in Africa to counterbalance China’s monopoly of the market, see: http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2015/02/10/guest-post-africas-role-in-addressing-chinas-dominance-of-rare-earths/.

From Sun Ra’s 1971 lecture at the University of California, Berkeley: https://sensitiveskinmagazine.com/wp-content/audio/Ra-Sun_Berkeley-Lecture_1971.mp3.