May 13–November 26, 2017

“Viva Arte Viva” is a tautological title. Since a tautological statement is one that is necessarily true on the basis of its circular syntactical structure, it’s logical to assume that Christine Macel, the curator of the 57th Venice Biennale, is asking us to believe that art is alive, and/or that we should all celebrate the celebration of art. Viva (hail) relates also to ovation (as in “Hail to the Chief”) and liturgical acclamation (like hooray or amen). So “Viva Arte Viva” begs for fervor and leaps of faith. After all, the descent of the biennale upon Venice is a 122-year-old cult, celebrated every two years in the same temples (pavilions and palazzos, but also yachts, vaporetti, and bars), with growing numbers of followers and replicas around the world. “The processions, circumambulations, singing, dancing, storytelling, food-sharing, fire-burning, incensing, drumming, and bell-ringing along with the body heat and active participation of the crowd create an overwhelming synesthetic environment and experience. At the same time, rituals embody values that instruct and mobilize participants.”1

The brief for the 2017 festivities seems as basic as it is infantilizing: keep it simple. “At a time of global disorder,” Macel writes, “the role, the voice and the responsibility of the artist are more crucial than ever before within the framework of contemporary debates.” But are they really, even within her framing? The curator avoids tackling distressing universal subjects like politics, populism, racism, or identity, preferring instead to group 120 individual positions in accordance to vague, conservative, and elementary (school) categories such as earth, traditions, colors, time, the common, books, joys, and fears. Each is associated with a “pavilion” (not a physical space, but simply a “chapter,” represented as a title printed on a map and placards on pillars marking the divisions). The only exception, in terms of an adult vocabulary, is the Dionysian pavilion, which Macel (who in 2005 curated an exhibition at Centre Pompidou titled “Dionysiac,” featuring an army of only male artists) here identifies with women artists, the female body, and its sexuality; adieu queerness and camp, farewell gender fluidity. The Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement went to Carolee Schneemann this year, in homage to her incendiary but faraway performance Meat Joy (1964), while the one for the Best Artist went to Franz Erhard Walther (coincidentally both artists were born in 1939).

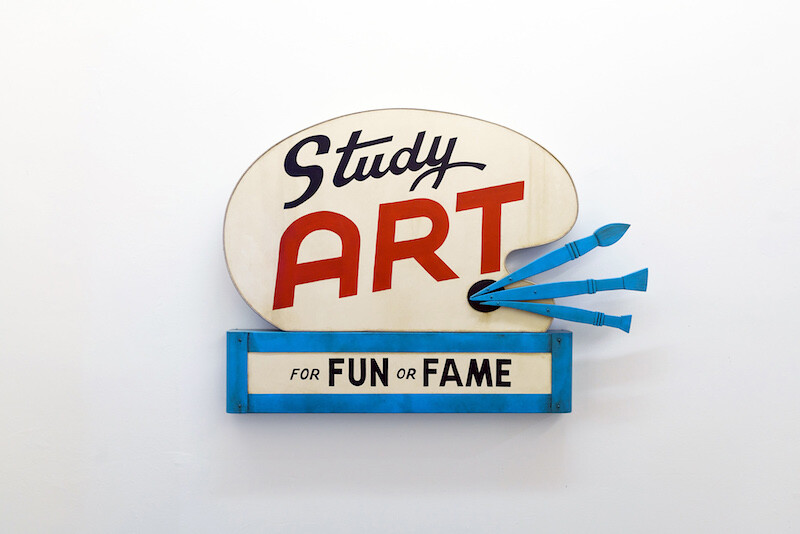

“Viva Arte Viva” is tautological also in its contents. For instance, in the pavilion of Books and Artists inside the Giardini, which is the starting point of the international section, one can find works on books (mostly rendered as unreadable) by John Latham, Ciprian Mureșan, Irma Blank, Ye Liu, and Jianyi Geng. In the first rooms—dedicated to otium, the idle time of relaxation and reflection defined in opposition to negotium, the time of business and networking in Roman times—one finds images of recumbent artists (Mladen Stilinović, Franz West). Even the notoriously disruptive sense of humor of John Waters, present with the series “Study Art Signs” (2007) that invites viewers to study art “for Prestige or Spite,” “For Profit or Hobby,” or “for Pride or Power,” seems tamed by the overall literal mode. Rachel Rose’s fairytale video animation Lake Valley (2016), following a lonely white rabbit in search of a place to call his own, is introduced as an illustration of “the reality of emotions.” We are used to algorithmic determinations of taste assembling random imagery. Macel’s filters seem pretty clear: artists are preferably “new” (103 of the 120 included have not exhibited in a previous Venice Biennale), peripheral, and producing a photogenic output. Statistics and figures, likes and dislikes, views and retweets—they all count. Besides a curatorial statement, the biennale is also a massive playground for travelers and an economic machine for its host city, where the paying public (over 500,000 visitors for the 2015 edition) must be able to circulate after pausing for a few seconds to read, enjoy, maybe snap, before moving on. Superficial consumption and social mediatization set the pace.

In fact, the Arsenale opens with The Circle of Fires (1979) by Juan Downey, a circle of monitors showing a group of videos where the Yanomami, an indigenous group from the Venezuelan and Brazilian Amazon, record on camera their own lives and celebrations, while the abstract fluoro-colored structures of Rasheed Araeen’s Zero to Infinity in Venice (2016–17) are there for the public to play with, to be deconstructed and reconstructed, Lego-style. Not an entirely new idea: in Totem and Taboos, over a century ago (1913), Freud situated the artist at home with the child and the “savage.”

One could try and compare this biennale with Documenta 14 in Athens. Both share a fractured structure, a number of artists involved in the ritual dimension (Araeen, Nevin Aladağ, Anna Halprin, David Lamelas, and Maria Lai, for instance) and occasional overlappings in the areas of research on the musical, the magical, the “native,” and the spiritually healing, but their strategies of communication diverge. While Documenta refuses to mediate complexity within the exhibition space (very little information is provided, besides author, title, and date) and hence causes a fair amount of frustration amongst connoisseurs and general public alike, “Viva Arte Viva” elevates user-friendliness and efficiency to stellar heights. Captions are evident and descriptive. On the website, the artists are introduced by a short video about their practice, often narrated in the first person. I was invited to join a Tavola Aperta (Open Table) with the Argentinian-born, New York-based Liliana Porter (co-founder in 1965, with artists Luis Camnitzer and José Guillermo Castillo, of the New York Graphic Workshop), where the artist spoke about her work, while surrounded by eating tablemates, as well as microphones and cameramen, since the whole lunch, like the performances in the public program, was recorded and livestreamed by the biennale’s Mediacenter. “VIVA” aptly translates also as live, i.e., in real time, since it feeds (and maybe overfeeds) our fears of missing out. By contrast, Porter’s work at the Arsenale, El hombre con el hacha y otras situaciones breves (Man with an axe and other brief situations, 2017), in the final pavilion of Time and Infinity, is a composition revolving around a minuscule figurine of a man trying to destroy all sort of objects and recollections—a sharply ironic commentary on memory, the current visual deluge, and the vital role that we assign to images.

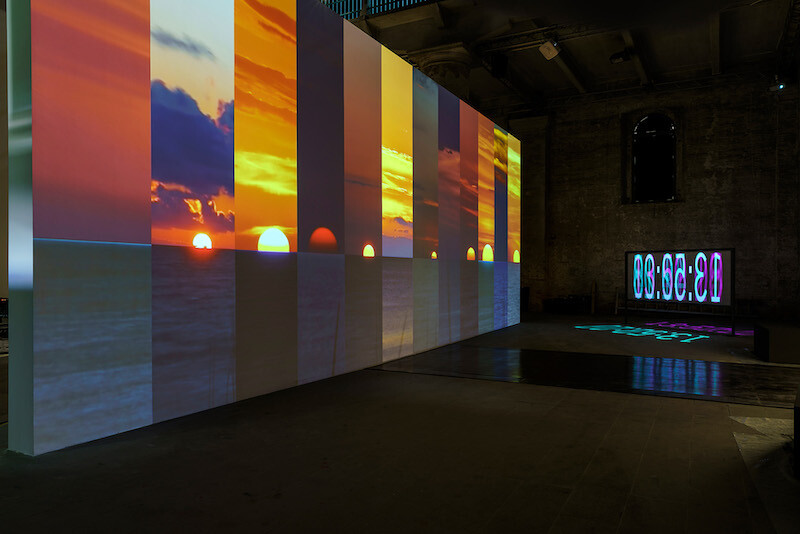

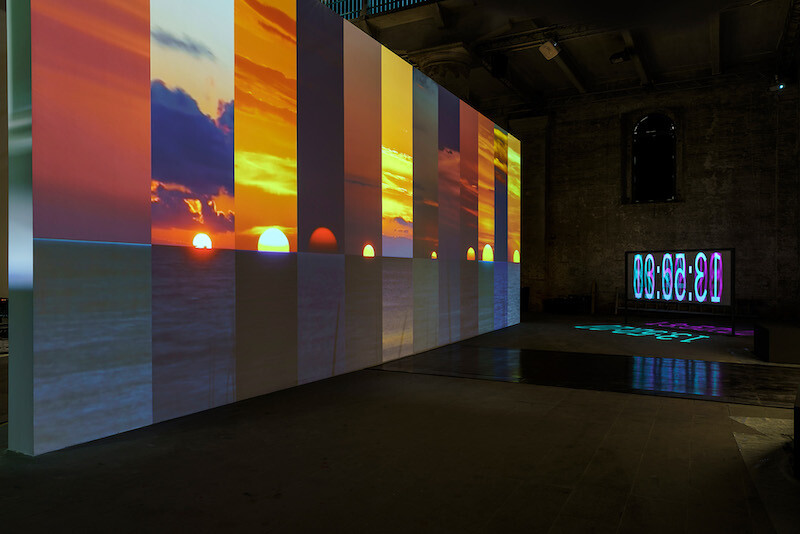

Another standout is The Tyranny of Consciousness (2017) by Charles Atlas, who was awarded a Special Mention, together with the young Kosovan/Italian artist Petrit Halilaj. It consists of an impressive multi-channel video installation simultaneously showing 44 sunsets in candy colors, in a perennial cycle of endings, accompanied by the voice of legendary New York drag queen Lady Bunny, who talks about peace, life together, and how, when it comes to US politics, “the right questions are never being asked.” The moment when Bunny’s face, framed by a massive, RuPaulesque, B-52’s-style blonde hairdo, appears as a massive projection, along with pounding disco music, marked one of my few Dionysiac experiences along this “journey.” And yet, I can remember the works of Leigh Bowery (another Atlasian icon) positioned more or less in the same spot during the 2005 Biennale (curated by Maria de Corral and Rosa Martinez, the first women to be handed the task), as well as the scenographic display of a grand dame of contemporary art at the end of the space (Louise Bourgeois back then, Sheila Hicks today, with her monumental, colorful, and selfie-irresistible Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands, 2016–17) and the exoticized presence of Amazonian Indians (at the opening ceremony, also in 2005, today in Ernesto Neto’s cupiwaxa nest/tent Un Sagrado Lugar [A Sacred Place, 2017]).

Rituals can be repetitive, prescriptive, and comforting, but they could also be transformative and unsettling. Little seems to have happened lately, in terms of innovating the structure of display and representation. One of the rare exceptions to the rhetoric of linearity in the Giardini seems to be the hilarious “The Aalto Natives,” a collaboration between Nathaniel Mellors and Erkka Nissinen for the Finnish pavilion, curated by Xander Karskens, where slapstick and CGI reshape national identities and alienation. Outside the biennale, “The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied.” at Fondazione Prada’s Ca’ Corner della Regina is an eight-handed project developed by artist Thomas Demand, curator Udo Kittelmann, filmmaker Alexander Kluge, and stage designer Anna Viebrock that fills the spaces of the ancient palazzo with a labyrinthine sequence of doors to be opened and rooms to be traversed. Disorientation ensues, while cross references migrate from a painting to the furniture of a period room, to the subject of a picture, to a detail of a video, to an actress in a film, so that facts and fictions, texts and hypertexts are constantly remixed, questioned, and reinvented.

At the Gallerie dell’Accademia, Philip Guston, with his formidable pink high pastes, wild klansman imagery, and homages to “Masaccio, Piero, Giotto, Tiepolo, De Chirico,” as he writes on a cartoonish painting (Pantheon, 1973), hammers away at the Cult of the Male (White) Genius with healthy doses of poetry and irony. This is not to be found in other temporary landmarks, like Damien Hirst’s sculpture towering over Palazzo Grassi, or James Lee Byars’s 20-meter-high lingham-like Golden Column (1990) in Campo San Vio, near the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.

Anne Imhof’s German pavilion exhibition “Faust” (curated by Susanne Pfeffer), winner of the Golden Lion for Best National Participation, gained maximum consensus by integrating the orgy of disembodied communication with the emotional urgency of the ritual. Doors are guarded by aggressive dogs and female bouncers, building up momentum, and when the happy few are finally introduced into the gated area, where music, vibrating sounds, throaty and choral chanting, headbanging, purifications and cyclical actions are choreographed by means of mobile communications (everybody has a phone and occasionally flips through it, or quickly types texts), the performance confronts the audience with the shallowness of its own gaze. If the raised glass platform that sometimes divides the public from the young, hip, picture-perfect performers is transparent, it’s also true that Imhof applied two-way mirror films to many surfaces, so that cameras and latest-generation iPhones end up capturing, most of all, the public itself.

At the core of Goethe’s Faust (1829), the epitome of German culture, the protagonist overcomes his intellectual crisis by resorting to an act of black magic. Which brings me to the apocalyptic darkness of the Italian pavilion (with works by Giorgio Andreotta Calò, Roberto Cuoghi, and Adelita Husni-Bey, curated by Cecilia Alemani), whose title comes from the book Il mondo magico (The Magic World) by anthropologist Ernesto de Martino. Magic makes its appearance in society, de Martino claims, in response to “a crisis of presence,” that is, when humans perceive the approaching end of their world (disclaimer: I wrote a text on Husni-Bey along similar lines). But human worlds, de Martino remarks, are always ending, one apocalypse after the other. After all, “Viva Arte Viva” could be an invocation, or maybe on order: “Lazarus, come forth!”2

Richard Schechner, “Ritual and Performance,” in Companion Encyclopedia of Anthropology: Humanity, Culture and Social Life, ed. by Tim Ingold (London and New York: Routledge, 1994), 632.

John 11:43. (King James Bible)