“Sonic Rebellion” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit offers two substantial proposals. First, it posits that the music of Detroit, ca. 1965–2000, was an active participant in the contemporaneous political and social struggles of the city, voicing and, in some cases, enacting resistance to the existing power structure. Second, it suggests that this conception of music and/as politics issues a call to the future, soliciting responses from contemporary artists including the well-known (Glenn Ligon, Juliana Huxtable, Cauleen Smith) and the somewhat lesser-known (Diamond Stingily, Ben Hall, Sterling Toles).

One leaves MOCAD feeling that the exhibition’s curator Jens Hoffmann is being deliberately coy about its theses.1 “Sonic Rebellion” presents historical artifacts and contemporary works, but not much context or information that would allow the spectator to engage with the show’s proposals. If, in fact, music participates in resistance, does it do so equally and by the same means, regardless of era, maker, genre, or issue? And what, precisely, is the relation of the historical artifacts in the exhibition to the contemporary artistic responses? Do the latter pay homage, revise, or amplify the positions and meanings of the former? The exhibition sidesteps such thorny questions and their thornier implications by adopting a curatorial attitude which seems to say “that’s for me to know and you to find out.” While I’m happy to do the finding out, the show offers little evidence of its own knowing.

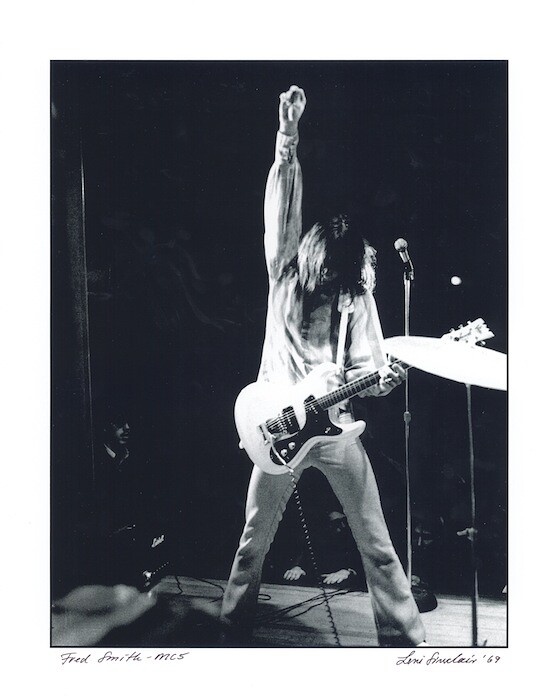

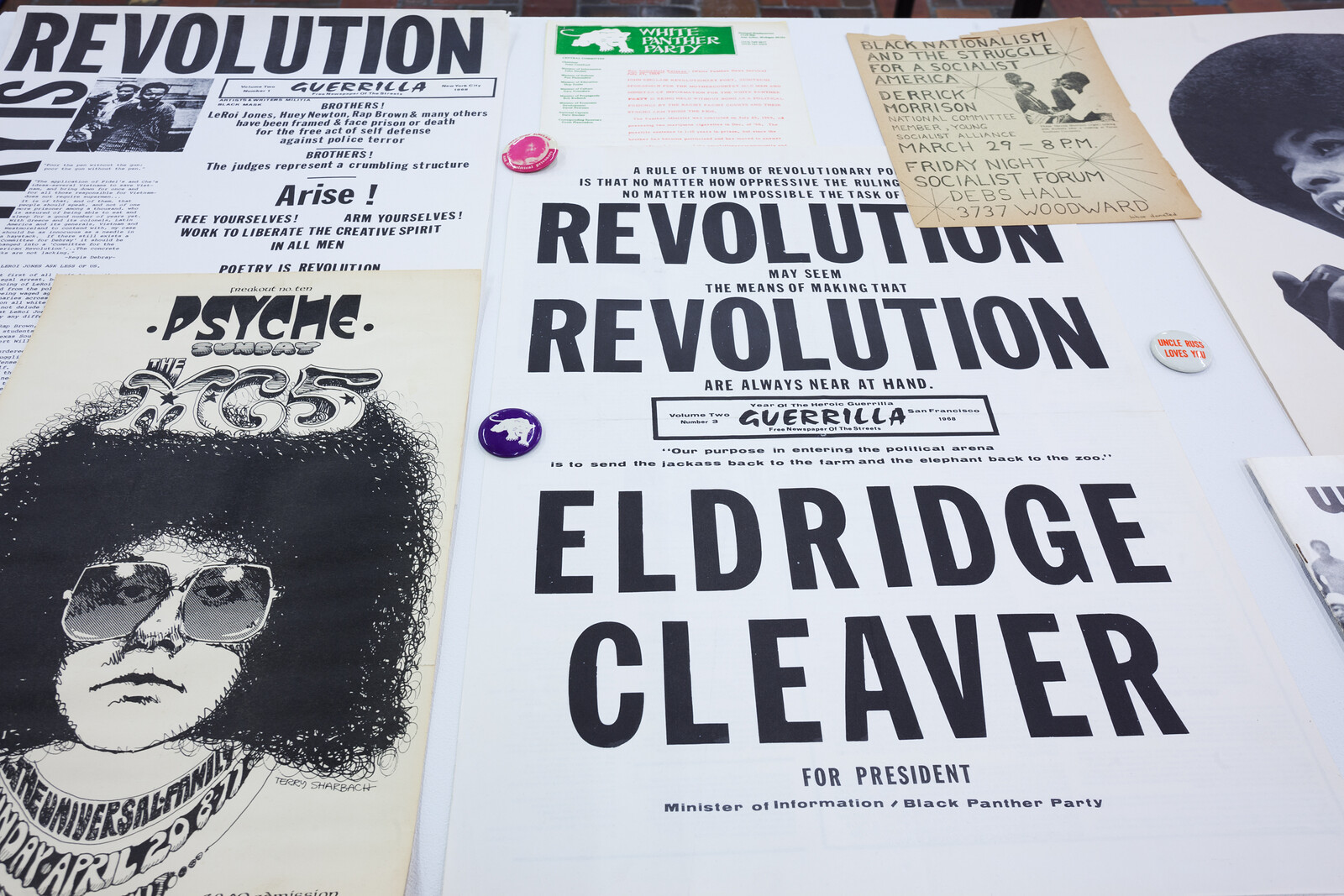

Early in the exhibition, we encounter four of Emory Douglas’s vivid graphics for the cover of The Black Panther newspaper. One issue proclaims 1971 “The Year of the Youth” and features a black boy, rifle in hand, challenging the camera with an expression of anxious recalcitrance. Later, a 1969 photograph depicts hard rockers the MC5, de facto figureheads of the White Panther Party, also holding rifles, victoriously above their heads, alongside a guitar and a saxophone. Douglas’s insurrectionist agitprop and the MC5’s publicity photo are granted a material equivalence via their treatment in the show—both are framed and hung as “works.” This material equivalence suggests an historical equivalence that is, in fact, equivocation, perpetuating the same distorted racialization that it blithely presents. The Black Panther Party was a revolutionary organization, which developed programs and platforms to oppose entrenched white power, while also providing essential services to the black community. Their leaders were systematically persecuted by overt and covert law enforcement efforts. Many were jailed. Many were murdered. The MC5, on the other hand, was a rock band. Its association with Detroit’s head beatnik, John Sinclair, connected it to the nascent White Panther Party, imagined as a sympathetic white counterpart to the Black Panthers. But the White Panther Party never materialized as a political or social force, and its greatest impact was as a marketing campaign for the band. “Sonic Rebellion” offers no tools to distinguish these histories and meanings.

As the cradle of the auto industry, Detroit has functioned as a laboratory for capitalism’s experiments. The auto assembly line produced the economic logic of “Fordism,” adopted by capitalism not just as method, but as philosophy. In the summer of 1967, the laboratory exploded in what came to be known as the Great Rebellion. Black residents battled the Detroit Police Department, the National Guard, and the United States Army. Forty-three people were killed, more than 1,100 were injured, and nearly 700 buildings burned to the ground.2 Detroit never recovered. By 2016, the city’s population had plummeted from a high of 1.8 million in 1950 to fewer than 673,000.3

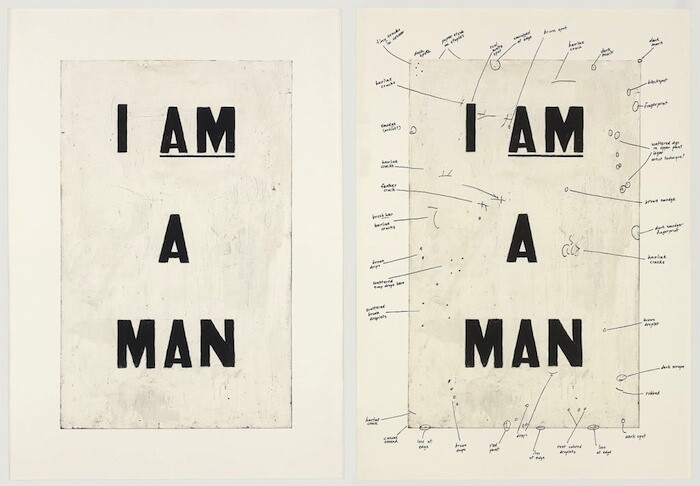

The most important questions raised by the exhibition are asked not by, but of it. Vitrines present pamphlets and newsletters produced by the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, two groups formed in the aftermath of the Great Rebellion to demand racial parity not only from Dodge, but also from the United Automobile Workers union. But the exhibition makes no effort to contextualize or explain the unprecedented historical fact of the emergence of a strong and significant Marxist movement organized by African American workers. The exhibition not only omits, but fails even to mention the movement’s definitive accounts: the 1970 film Finally Got The News, produced by the League, and the 1975 book Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, by Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin. Hoffmann seems oblivious to the immanent critique offered by Ligon’s sly and bracing Condition Report (2000). Two adjacent prints display the same phrase, borrowed from placards carried by Memphis sanitation workers during their 1968 strike: “I AM A MAN.” One of the two prints also includes some three dozen handwritten comments identifying blemishes and smudges on the print’s surface. Here, in distilled form, is the operational logic of the exhibition: struggle as adornment, history as raw material for the culture industries.

In late December, in the wake of sexual harassment allegations by staffers at the Jewish Museum in New York, Hoffman resigned his position at MOCAD. His globe-trotting practice, peppered with at-large and one-off assignments in New York, Paris, Buenos Aires, Paris, Honolulu, Cleveland, and Detroit, does not prioritize sustained engagement with individuals, communities, or situations. “Sonic Rebellion” is undermined by a similarly cursory acceptance of Detroit’s politics as a decoration for a slight conception of both social conflict and contemporary art. The exhibition papers over the vexing imbrications of art, race, and economics in the lives of Detroiters. In order to take seriously the exhibition’s claims about the relationship between political and artistic activity, it would be imperative to think in terms of engagement rather than entertainment; attunement rather than attainment.

The exhibition is curated by Jens Hoffman and Susanne Feld Hilberry together with Robin K. Williams.

Robyn Meredith, “5 Days in 1967 Still Shake Detroit,” New York Times, July 23, 1997. http://www.nytimes.com/1997/07/23/us/5-days-in-1967-still-shake-detroit.html.

Kristi Tanner, “Detroit’s population still down, despite hopes,” Detroit Free Press, May 25, 2017. https://www.freep.com/story/news/2017/05/25/new-census-data-show-detroits-population-decline-continues/341336001/.