On arriving in Japan in 1933, the German architect Bruno Taut (1880–1938) declared: “When modern architecture first came into being around the 1920s, it was the simple and entirely free Japanese living room, with its large windows, wall cupboards, and the purity of its design that provided the strongest impetus for the simplification of the European living space.”1 Taut shared the belief that a progressive design contributed to the edification of an emancipated society with the Bauhaus, the “School of Building” founded in Weimar in 1919 by his contemporary Walter Gropius (1883–1969). In the books he wrote during his stay in Japan, Taut reflected on the functional and simple qualities of Japanese architecture and design, comparing them with the western modernist values of his time.2

Held at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, the first chapter of the exhibition series “bauhaus imaginista: Corresponding With” does a parallel operation by unveiling the exchanges between the Weimar school and parallel educational contexts in Japan and India. More precisely, the show offers an accurate, serious, and elegant observation of the contemporaneous reformist purposes of three pedagogical institutions: the Bauhaus; the School of New Architecture and Design (former Research Institute for Life Configurations), co-founded by Renshichiro Kawakita in Tokyo in 1931; and the Kala Bhavana, the institute of fine arts founded in 1919 by poet and educator Rabindranath Tagore in Santiniketan, West Bengal. The exhibition advances not through the presentation of definitive, canonical pieces by educators but via the display of works, sketches, documents, and pedagogic materials made and used by some of its students. In doing so, it experiments with the sharing of the deeds of these pedagogical experiences beyond the strict presentation of support documentation and secondhand narratives.

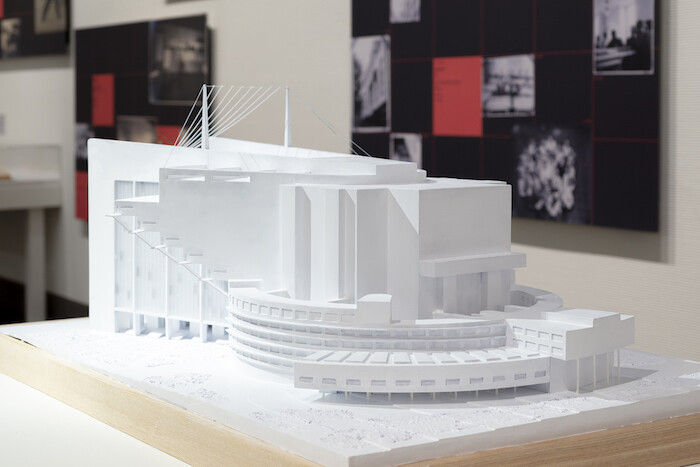

This curatorial criterion justifies the profusion of fragile, medium-sized materials that constitute “Corresponding With”—many of which aren’t artworks but testimonies of articulated systems of circulation of ideas and aesthetics. Spatially, the exhibition gravitates around three centripetal axes: Takehiko Mizutani’s sculpture Brass sheets cut into circular shapes and intersected, made in 1927 when he attendanded the preliminary course taught by Josef Albers; Luca Frei’s commissioned installation Model for a Pedagogical Vehicle (2018); and a set of four pieces of teak furniture from the 1930s—a stool, low chair, recliner, and low table—designed by Ratindranath Tagore, Rabindranath’s eldest son, after his trip to Japan.

Formally, Takehiko Mizutani’s piece opens and closes the exhibition with an iridescent swirl and a wink to kinetic fluidity. Placed at the center of the first gallery atop a thin pedestal, the medium-scale golden sculpture is representative of the Bauhaus’s syncretism. It is an in-between object, an educational prop, neither prototype nor finalized exemplar; a flat brass sheet that, in being bended, becomes a volume; and an insinuation of a pair of cymbals and of Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1919–20): movement, sound, craftsmanship, design, and architecture folded into one another. Brass sheets cut into circular shapes and intersected is also paradigmatic of the permeability of the ideas that traversed the Bauhaus across mentors and pupils. The sculpture echoes the Möbius strips of Max Bill, also a student at the Bauhaus in 1927 (and who later on assured the continuity of its ideals onto the Ulm School of Design, of which he was the first rector), as well as Oskar Schlemmer’s “Grotesque” series (1923/64) of half-humanoid, half-musical instrument figures.

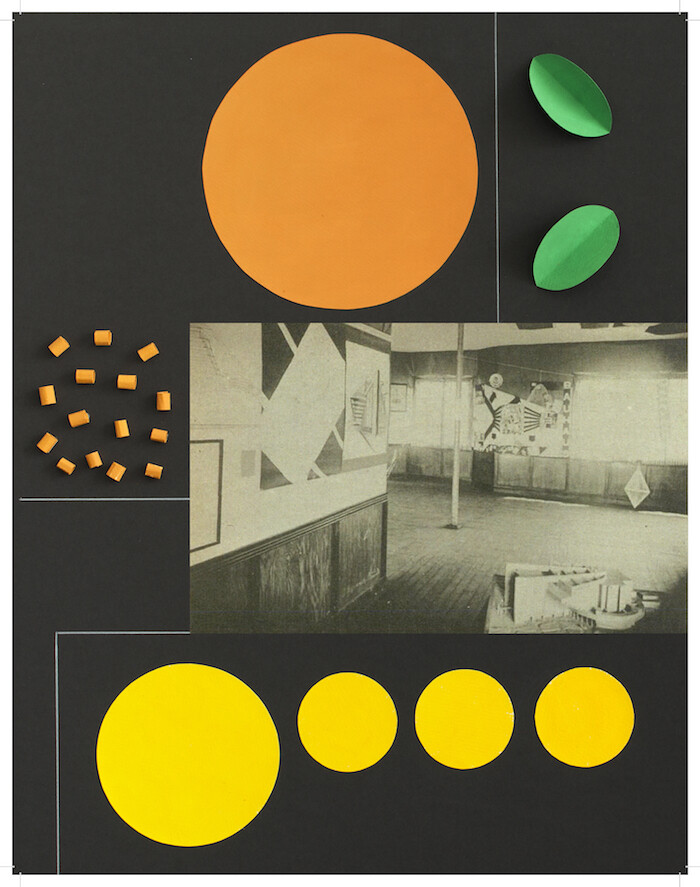

Luca Frei’s Model for a Pedagogical Vehicle, presented in another room, inserts itself with well-balanced elegance, accuracy, and inventiveness within the complex (and often troubled) canon of the remake of historical exhibitions. Model for a Pedagogical Vehicle restages “Exhibition of Life Construction,” a show conceived by Kawakita and Mizutani and held in Tokyo in 1931, which played a fundamental role in first introducing the Bauhaus to Japanese audiences. The exhibition was also the starting point for Kawakita’s Research Institute of Life Construction (1931–36), whose educational principles combined a careful attention to Japanese and western modernism with an industrial production agenda and an affiliation to the Bauhaus pedagogical methodology, namely the adoption of its preliminary course. Frei’s Pedagogical Vehicle appropriates the space around it, becoming an environment in which a portable structure referencing a prop of the post–World War II Japanese transdisciplinary collective Jikken Kōbō [Experimental Workshop] holds four black-and-white photos of “Exhibition of Life Construction.” Four reconstructions of paper studies featured in the images, made in collaboration with artist Eric Gjerde, are also hanging from it, accompanied by a set of large cushions that, by transposing the design of a ceiling diagram presented in the original 1931 exhibition to the floor, create a perceptive hiatus that proposes a humorous moment in the otherwise composed and dry environment of the exhibition as a whole.

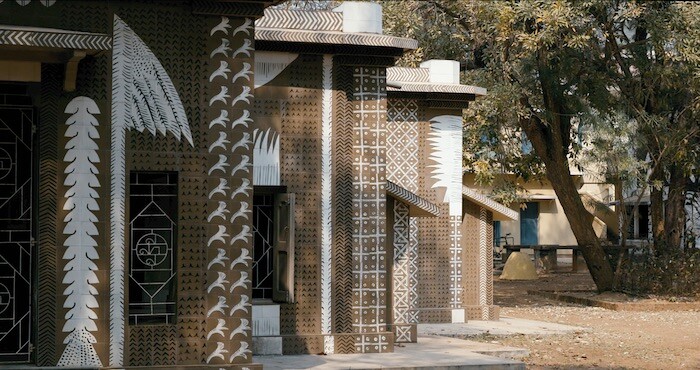

Ratindranath Tagore’s four furniture items introduce an element of elegant, almost stately domesticity to the exhibition, while materializing the importance of object design and the integration of arts and crafts within the three pedagogical agendas surveyed by the exhibition. If the suppression of the old regime in post–World War I Germany opened way for the embrace of the ideals of modernism that shaped the Bauhaus, inversely, the flattening dominance of the British Raj asked for the urgent rehabilitation and modernization of India’s cultural landscape, a movement embodied by Rabindranath Tagore’s persona and operated through such initiatives as Kala Bhavana. Portraying the school’s aims are the instructional postcards made by its principal, modern art pioneering artist Nandalal Bose (1882–1966); Otolith Group’s new film O Horizon (2018), which brings a moment of unique warmth, colorfulness, and sensuality to the exhibition, with its tribute-portrait to Tagore’s holistic take on environment and culture and the role that education played in the transmission of fundamental values; as well as Tagore’s own writings, in which he criticizes the imposition of western education models in India and its system of perpetuation of imperialism and promotes the decolonization of pedagogical methods.

Expanding Tagore’s progressive, anticolonial message to a meta-reflection about the reception and comprehension of the Bauhaus, one of the aims of the exhibition’s curators Marion von Osten and Grant Watson was that of decolonizing the dominant narratives that shape the Bauhaus, strengthening other, non-western exchanges and interpretations. However, in centralizing the relationships of the two Asian contexts toward a self-referential, German axis, the exhibition misses the opportunity to engage in wider Pan-Asian debates, and one is left to wonder what were the correspondences between Japanese and Indian modernisms within a triangle that is perhaps left incomplete.

At the same time, revisiting the opening account on Taut, it should also not be forgotten that, as a Jewish man who openly embraced socialist values, Taut went to Japan in 1933 to flee the establishment of Nazi Germany—the same year that the Bauhaus was shut down by the Gestapo. It was a result of the dispersion of its members that the Bauhaus ideals gained such a wide international diffusion. “Corresponding With” aims to reflect the global resonance of the Bauhaus, but the political circumstances that gave rise to this diaspora might also be taken in consideration.

However, this is only one of a large set of exhibitions and symposia taking place in eight countries, which compose the entire “bauhaus imaginista” project.3 Sections of the individual events will be assembled at Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt in spring 2019, where, beyond the celebration of an upmost icon of German export and cultural identity, one hopes to encounter the good occasion for the grand finale evaluation of Modernism’s legacy.

Quoted from Jeanette Kunsmann, “Lernen von Japan—Schlichtheit in Fernost,” in Deutschen Architektenblatts, November 30, 2012, (https://dabonline.de/2012/11/30/schlichtheit-in-fernost-japan-bescheidene-haeuser/. (Author’s translation from German).

Nippon Seen with European Eyes (1934), A Personal View on Japanese Culture (1936), Fundamentals of Japanese Architecture (1936), and Houses and People of Japan (1937).

With events and projects in Brazil, China, India, Japan, Morocco, Nigeria, Russia, and the USA, “bauhaus imaginista” is part of the 2019 celebration of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Bauhaus. The initiative’s budget largely exceeds that of Documenta 14, also comprises the building of three new museums in Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin. It is supported by the German Bundestag and Federal Government, represented by the Commissioner for Culture and Media (BKM), together with 10 German federal states.