The exhibition’s title, alliteration and all, has the ring of an Aesopian fable. The Latin etymology of monument, Michael Rakowitz spells out on the edges of a sculpture, are trifold: caution (to remind, to advise, to warn), protest (demonstrate, remonstrate), monstrosity (monster). And indeed, around the gallery, the monstrous is everywhere in sight. Its forms are many: to the right, Behemoth (all works 2022), a colossal black plastic tarp obscuring the suggestion of an equestrian figure below rises tall only to fall to the ground as the fan powering its ascent clocks out. At the center, American Golem, poised on a decorative white wooden tabletop, an assemblage of found antiques and papier mâché sculptures (a strategy the artist has previously used for reproducing objects looted from Iraqi museums, highlighting the calls for their repatriation).1 The central figure, which stands on a stack of marble slabs, greets the viewer from the top of its bell-mold body and fired-clay mask—a copy of the Babylonian monster Humbaba. Gazing out at the viewer, its composite arms outstretched, it recalls Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920), but even more grotesque. It doesn’t just stand on the wreckage of the past, propelled toward the future: it is the debris itself.

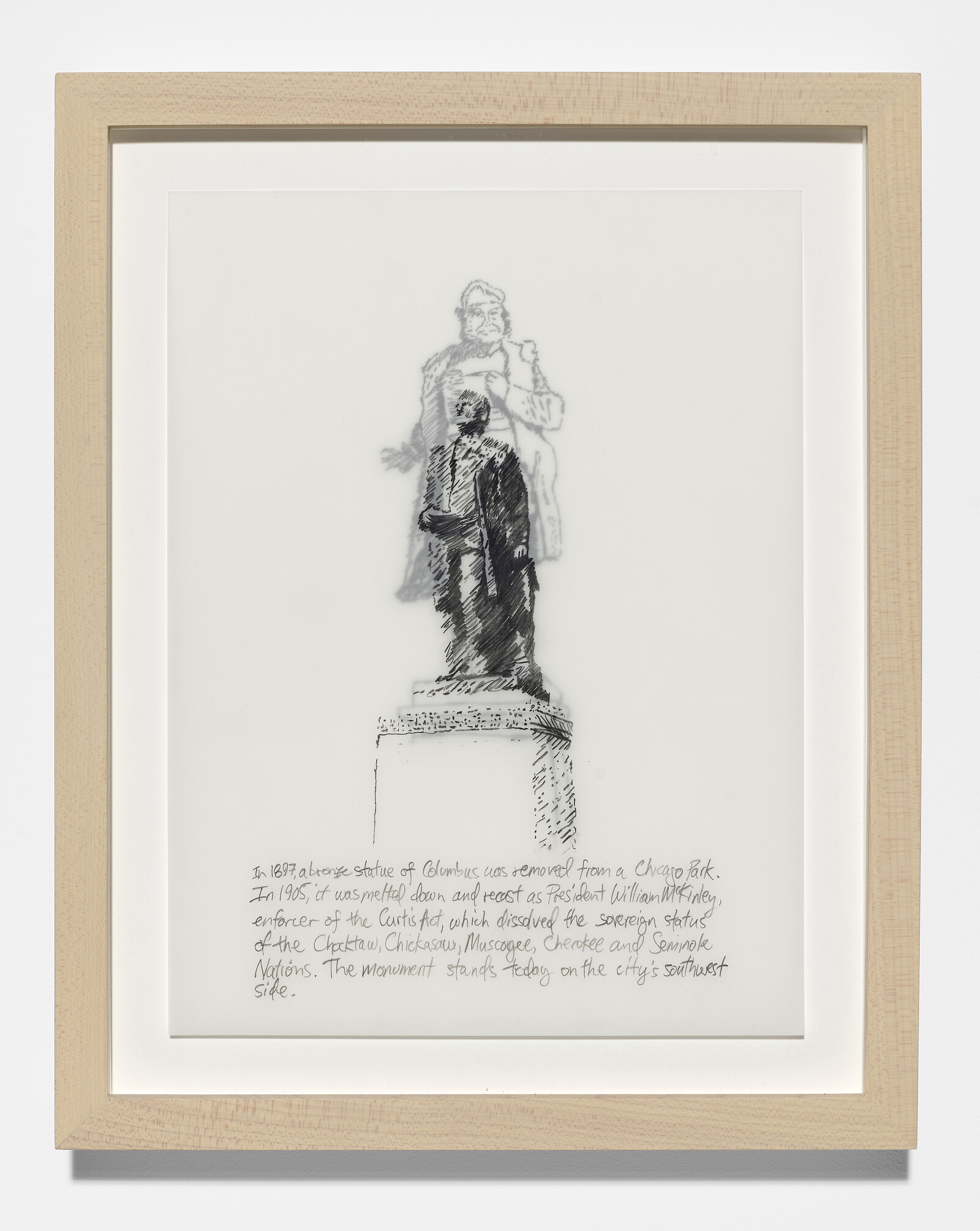

The exhibition is a neat presentation of the artist’s research on the social and material history of monuments. The most distilled of the works on show offers a methodological precis. Five framed drawings on architectural velum, Monuments in Spolia, function as historical palimpsests: in the foreground, the extant sculpture that has supplanted the former toppled or melted or transmogrified monument, which haunts the image in the background. In no.1, for instance, a statue of Lenin in Odessa is refashioned as Darth Vader by the artist Aleksandr Milov as part of Ukraine’s 2015 decommunization legislation. Rakowitz pens a caption below the image which concludes: “His helmet emits free Wi-Fi.”

The resulting superimpositions present as orderly compositions, emphasizing continuity rather than change. Take the 1893 monument to Columbus in Grant Park, Chicago, relocated to storage after fervent critique, and melted and recast in 1897 into one of President William McKinley, dedicated in 1905. It still stands erect in a namesake park in Chicago today. From 1492 to the continued dispossession of Indigenous land and sovereignty—McKinley championed the 1898 Curtis Act, an amendment to the Dawes Act that abolished tribal court—these historical juxtapositions do not interrupt the colonial continuum. What interests Rakowitz is perhaps less the ways in which one edifice comes to replace another, than what conditions lead a monument to be erected and another to come down. When does a monument become visible again? And what remains of the past in the present?

Rakowitz traces the lives of contested monuments as much through the debates and protests they spur as through their material constitution. “Spolia,” after all, means recycling: repurposing architectural fragments as decorative or structural elements for a new construction. He looks, for instance, at Greek bronzes destroyed during the Roman general Sulla’s sack of Athens in the first century BCE, then turned to coins bearing his likeness; or to tin and lead from an eighteenth-century statue of King George III used for musket balls in the Revolutionary War. These drawings serve, as Rakowitz stated in a tour of the exhibition, as “propositional of different possibilities,” perhaps pointing to other ways of thinking about repatriation: “What would it mean,” he asked, in conversation with scholar Erin L. Thompson, “to repatriate that material […]? To separate the copper from the tin that makes the bronze and give it back to the land?”

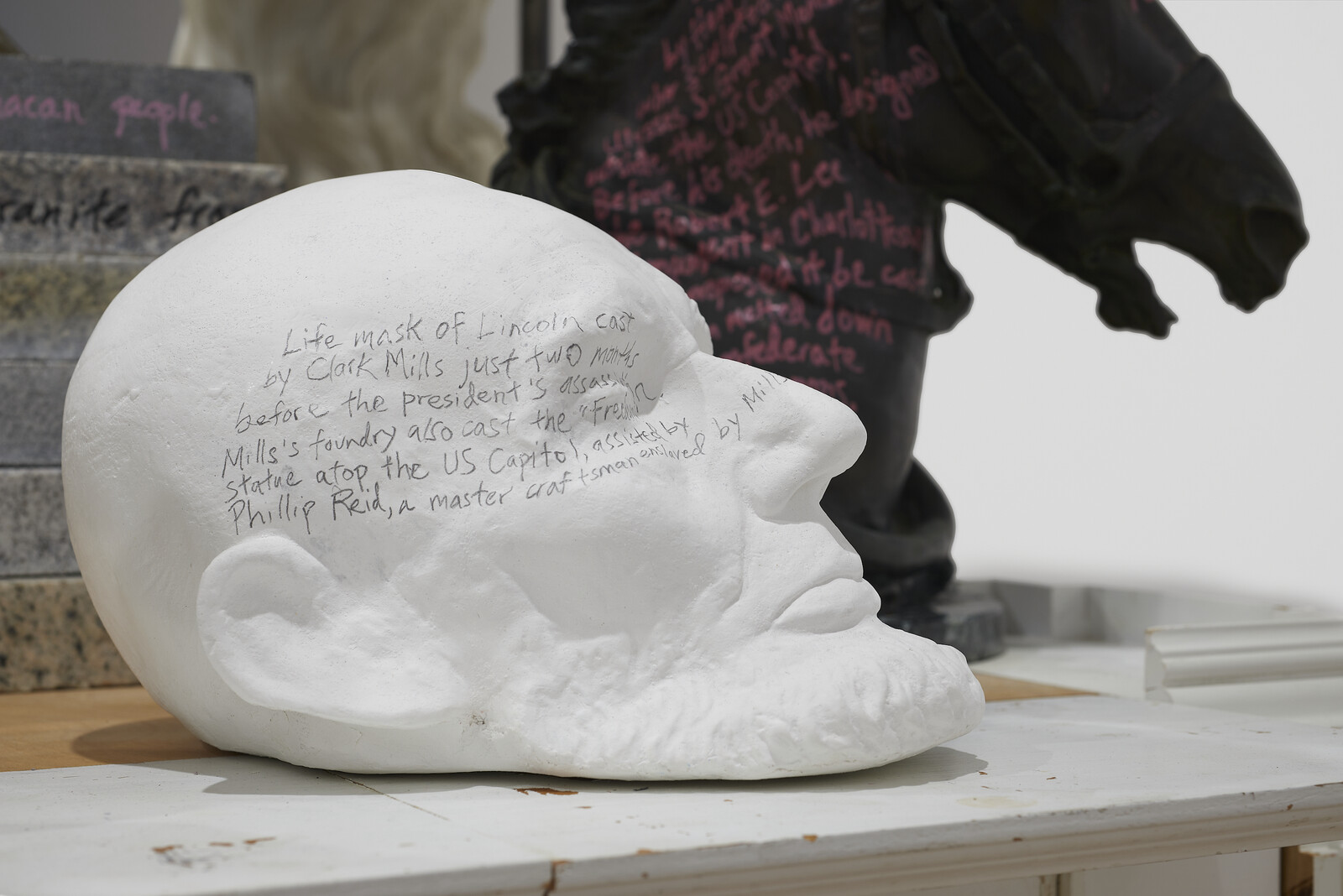

Rakowitz’s forensic approach to spolia takes three-dimensional form in the towering American Golem, a work that requires and rewards close reading. Each element making up the sculpture bears the artist’s handwritten annotations, identifying the cited monument or object’s historical provenance, intended purpose, material composition and the details of its original fabrication and maker, and where relevant, a brief contextual account of recent toppling, following in particular, the renewed calls for reckoning in the wake of 2020 BLM protests. Symbols of colonial and imperial power, of the afterlives of slavery and the Confederacy, of World’s Fairs, of Indigenous land extractivism and occupation, of looting of cultural heritage: the twenty objects that make up the work are salient examples from a much larger possible repertoire. But what transpires in these accounts, each more indicting than the next in their impassive delivery of facts, is the sheer weight of accumulated evidence.

Rakowitz’s annotations, scribbled along the sides of presidential death masks, the busts of portraits, and the flanks of militarized horses, certainly augment the inventory of selected objects, offering a tightly plotted path through the ample metadata of this contested archive. And it is the tracing of their material history that is perhaps most illuminating. Yet the maximalist approach to writing here, albeit rendered with the humility of the handwritten scrawl, surfaces a primary tension. The artist himself insists that the kind of contextualization of monuments in the form of captions or interpretative plaques and media that would contend with their complex histories—a more conservative tactic often floated to avoid their removal—is complacent at best. “It doesn’t deal with the material culture of the sculpture itself or the historical material it’s meant to symbolize,” he said to Thompson. But while this prolific gloss eschews the voice of institutional authority and its disingenuities, the sheer volume of text runs other risks: information overload and its attendant forms of inattention and exhaustion.

It is perhaps the most tired, abstract, and mute of Rakowitz’s monsters, then, that speaks the loudest in response to the ongoing demand that all monuments must fall. In its looping cycle of surge and collapse, the massive inflatable Behemoth would seem to quite literally compress the timescapes that have seen these statues rise and fall. But in referencing the temporary coverings laid and strapped over public monuments as their fate is debated by city councils and advocacy groups, it also adopts all the ambivalence of that state of provisionality, wherein the proceedings of social dissension and official national response are stalled, the promise of historical reckoning deferred. Behemoth, and other works in the show, for that matter, aren’t quite counter-monumental proposals or blueprints—as the titular “maquette” might suggest. Yet they do metabolize a feeling: that history’s monsters are not to be exorcised, they’re yet to find their final form. Rather than erect new monuments in the place of their toppled predecessors, Rakowitz has suggested, we could keep only their marble bases, the wreckage, the debris, graffitied and scrawled upon by protesters. Like a fable, the moral would lie out in public, for all to read.

See the ongoing project, The invisible enemy should not exist, 2007–:https://www.michaelrakowitz.com/the-invisible-enemy-should-not-exist.