The Chinese term gūanxi describes a web of relations between friends, family, lovers, co-workers, even corrupt politicians. It evokes a sense of community and belonging that can prove elusive for the diverse group of people commonly referred to as “Chinese American.” A moniker that points to allegiances, however fraught, to the two countries it references, “Chinese American” is a one-size-fits-all label that attempts to forge a singular identity out of a heterogeneous array of diasporic experiences shaped by displacement, immigration, and cross-cultural translation.

Curated by Dr. Jenny Lin, “Another Beautiful Country: Moving Images by Chinese American Artists” hinges on another transcultural exchange. Drawing connections between gūanxi and French-Martinican philosopher of opacity Édouard Glissant’s notion of a “poetics of relation,” the exhibition posits relationality over identity as an alternate cornerstone of contemporary Chinese Americanness.1 Referenced in an introductory essay in the exhibition catalogue written by Dr. Lin, Glissant’s emphasis on diasporic relation is espoused throughout the show—which includes areas for repose and relation amongst exhibition-goers—and enacted through real and speculative social encounters between family, friends, and strangers staged within the works themselves. Drawing its title from the Chinese word for America, 美國/měiguó, which translates literally to “beautiful country,” along with the popular shorthand for “American-born Chinese” (ABC), it offers a collective reflection on the slippery mutability of Chinese American identity and the relations that come to define it.

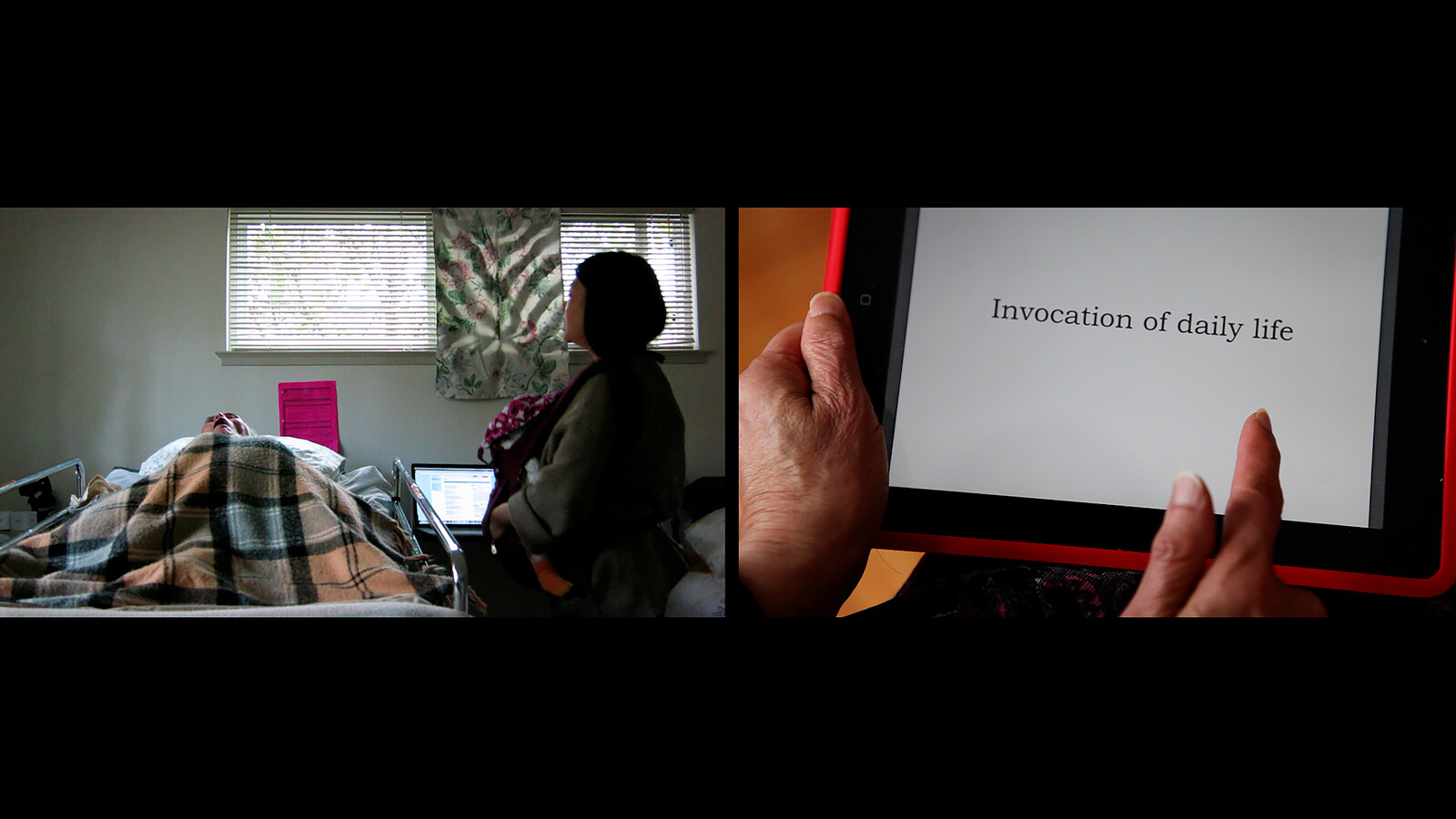

Working across video, installation, photography, language, and performance, the artists in “ABC” produce images that “move” both literally and affectively. Diasporic familial relations are foregrounded throughout. Taiwan-born, US-based Charlene Liu’s qípáo prints, Red Dress, Petals Undone, and Perfect Brightness (2015), for example, feature digitally manipulated photographs of qípáos hailing from both the artist’s and curator’s families. These adorn a wall of her large-scale installation China Palace (2023), an in-situ recreation of the artist’s mother’s now-shuttered Chinese restaurant, formerly located in a Wisconsin strip mall. In Patty Chang’s video performance, Que Sera Sera (2013), the artist is seen singing the titular song to her father on his deathbed, while rocking her newborn son to sleep, in an ephemeral intergenerational encounter. Ken Lum’s photograph, Coming Soon, 2009 (presented as a public billboard in Munich, Beijing, and Vienna), presents a staged interracial Chinese-Causasian couple and their mixed-race progeny, bearing the foreboding announcement, “coming soon,” in Chinese and English.

The early twentieth-century archival prints of Qing Dynasty family members that make up Hong Kong-born, US-based Simon Leung’s Family / Archive (2023) were in fact taken in St. Louis, Missouri, where his great-great-grandfather served as Vice-Commissioner of the Chinese Pavilion of the 1904 World’s Fair, in a rare exception to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Richard Fung was born in Trinidad to Chinese parents; his video The Way to My Father’s Village (1988) narrates an ambivalent return to the artist’s father’s hometown in China, where Fung feels like a perpetual outsider, locked out of both language and culture—countering grand narratives of a diasporic “homeland” that would, despite distance and difference, actually feel like home.

Rania Ho also cultivates looser forms of “relationality” in performance works that document karaoke encounters between strangers and an intervention into a former site of artistic gathering, respectively. You Kinda Had To Be There (Motel Cali) (both works 2023) is a video documenting a 24-hour performance in Beijing in the mid-aughts. In Roundabout, the artist sprays water on the ground while walking in concentric circles to “decontaminate” the site of recently demolished artist studios in Beijing—a reference to Covid-19 sanitation practices and the city’s disappearing artist communities. Other pieces perform subversive odes to pleasure. Candice Lin’s included kinetic installation, Lithium Sex Demon Workstation (2023), for instance, highlights the speculative relationships between imaginary migrant workers in a Chinese lithium battery factory who rebel and become “sex demons,” while Jennifer Ling Datchuk showcases a neon wall sculpture and doormat that read “Love Yourself Longtime.” The latter put in a self-care twist on the racist, subjugating line from Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987).

While references to Glissant and his poetics of relation have become familiar within the context of contemporary art, they are perhaps less so to the kind of audience that the USC Pacific Asia Museum seeks most ardently to address: the local, intergenerational Asian American community. Indeed, PAM is one of the few art museums in the Greater Los Angeles area to cater specifically to this community (despite its architectural embodiment of staid Orientalist fantasies). The transposition of a Franco-Caribbean poetics of relation to a Chinese American context via the evocation of gūanxi constitutes a significant intervention into an oft-theorized terrain. This relationality/gūanxi framework constitutes the organizing force of an exhibition that highlights an elusive sense of a collective Chinese American identity—one that, in a challenge to its own representation, is forever shifting and in flux, defined through relation rather than ontology.

Without explicitly reflecting on US-China relations, or indeed either country’s current political agendas, “Another Beautiful Country” situates itself firmly on the level of the diasporic individual/community rather than that of the nation-state, reminding us of the “diasporic subject[’s] inability to fully identify with a single nationality.”2 This shift in focus away from the “motherland” overcomes the always illusory origin stories that would trace us back to China, or a sense of national belonging that would situate us firmly as American. What emerges instead is a kind of grassroots collectivity, a hybrid child mapping out an emancipatory, if unsteady, new terrain—one grounded not in isolated quests for elusive origin myths or national identification, but in a speculative poetics of Chinese American gūanxi.

See Édouard Glissant, Poétique de la relation (Paris: Gallimard, 1990).

Exhibition catalogue.