Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

April 24, 2024 – Review

Gervane de Paula’s “como é bom viver em Mato Grosso”

Oliver Basciano

I entered Gervane de Paula’s three-room retrospective by the wrong door, meaning that I saw this chronological survey in reverse order. By the time I came to view the works with which the exhibition is supposed to open—the artist’s earliest paintings, from the 1970s, show sunny scenes of life in his home state of Mato Grosso, in the Central-West Region of Brazil—I was aware of the dark clouds that would gather over his vivid later canvases and Arte Popular-inspired sculptures.

This knowledge of the artist’s development heightened my sensitivity to the uneasy details that creep into even the most bucolic of de Paula’s first works and foreshadow his later career. Barro Araés (1977), for example, makes plain the artist’s deep affection for his local neighborhood in Cuiabá, the capital city of Mato Grosso: in the foreground, children play with kites in front of their single-story homes while, further back, their mothers hang washing on lines strung across the communal grassy ground, the brightly colored clothes matched by the palette of the airborne stick and paper toys. You can almost smell the Sunday pamonha boiling in the food cart a man pushes past the houses. Yet my eyes were drawn to …

March 6, 2023 – Review

Regina José Galindo’s “Anestesia, Anistia, Amnesia”

Oliver Basciano

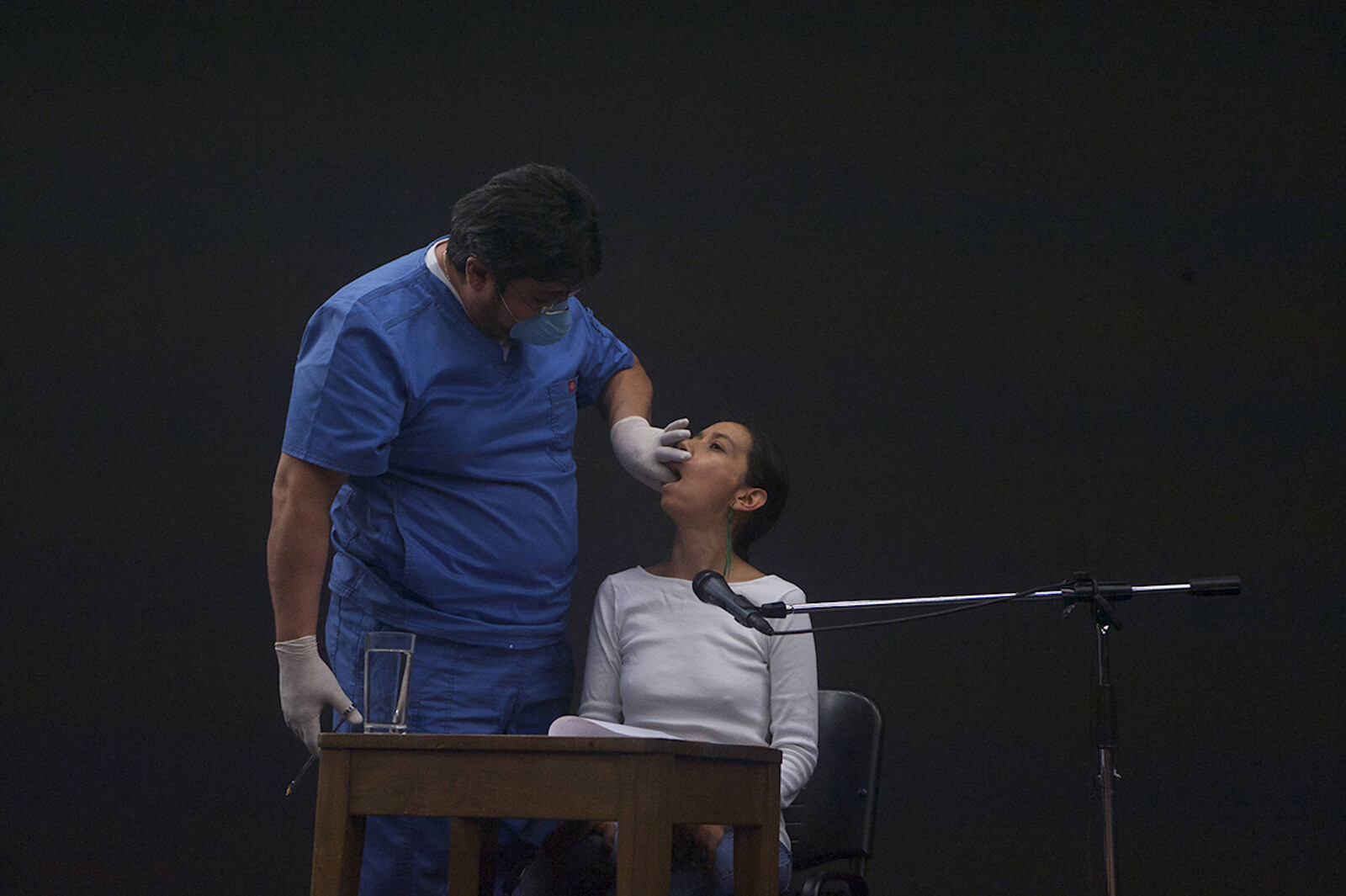

In 1960, angered by the deeply skewed land deals between the right-wing dictatorship and US companies such as United Fruit, a group of left-wing army officers tried to wrest control of Guatemala. They failed and over the ensuing 36 years, tacitly aided by Washington, the government coordinated the murder and disappearance of an estimated 200,000 people, most of them indigenous Maya civilians. In her video La Verdad (2013), for more than an hour, the Guatemalan performance artist Regina José Galindo reads out traumatic testimonies from the victims of these events.

Shot from a single static camera, it is the first of three documentary works in this small show, each of which is given its own room. Galindo wears a white top against a black background, reading in monotonous Spanish from a stapled block of paper: “they took out the baby and tied it up and there were some who got together to make a fire.” It continues in this gruesome and unsettling vein until, around five minutes in, a man enters the frame. Galindo stops reading and puts her head back. The man injects a dental anesthetic into her gums. As the drugs begin to work, the artist continues, her …

September 13, 2022 – Review

“Histórias Brasileiras”

Oliver Basciano

“Histórias Brasileiras” [Brazilian Stories] is a profoundly depressing show, a curatorial snapshot of a country, it would seem, at the end of its tether. It coincides with the closing months of Jair Bolsonaro’s grueling first term as the country’s president, opening just before the world’s fourth biggest democracy goes to the polls. The complaints and traumas presented in the exhibition are legion. That does not, however, necessarily make it a great exhibition.

Adherents of Bolsonarismo have long co-opted Brazil’s national flag. And so it is as a presumed rebuke that the curators present a series of reimagined versions of the blue, yellow, and green standard to open this sprawling exhibition (over 400 objects divided between eight thematic chapters, the first of which is titled “Flags”). Abdias Nascimento’s Okê Oxóssi (1970), in which the late artist and activist inserts symbols of Candomblé, the Afro-Brazilian religion, into the composition and palette of the original national design, subverts the European Christianity that has long held power in the country. It hangs alongside Mulambö’s Remembering Thy Noble Presence (2021), a funereal silhouette of the globe and diamond motif made from black plastic rubbish bags; and Leandro Vieira’s Brazilian Flag (2019), a rendition of the …

May 10, 2022 – Review

Paulo Nazareth’s “Vuadora”

Oliver Basciano

I often stare open-mouthed at Brazilian supermarket shelves, horrified by the overt racism of some of the branding. One line of cleaning products features a caricature that’s too grim to go into, and would likely have been considered offensive by many as far back as the 1920s. There is a history to all this of course. While they number under half the population, white Brazilians still hold a disproportionate amount of the country’s wealth and power: a legacy of colonialism, slavery, extractionism, but also of the myth of Brazil’s post-racial utopia to which many in the country still cling (a multiculturalism partly due to the post-abolitionist government’s desire to “whiten” the population by inviting immigration from Europe and Asia in the late nineteenth century). That is a lot to unpack from the weekly shop.

Some of these dubiously branded products caught the eye of Brazilian artist Paulo Nazareth too, who uses them as the basis for his critique of the art world’s tendency to transform cultural identity into commercial capital. In his series “Ovo de Colombo” (Egg of Columbus, 2020), one of the first bodies of works encountered in this expansive retrospective of art made over 17 years, they …

December 16, 2021 – Review

“The Machine of the World: Art and Industry in Brazil”

Oliver Basciano

A few days before I visited the Pinacoteca, I witnessed a traffic accident. At a busy intersection in downtown São Paulo—medics and military police already in attendance—a motorcyclist lay on the oily tarmac, his crumpled bike to one side. He was going to survive, it seemed, but his recuperation might take a while. Particularly telling was the fluorescent orange food delivery box abandoned on the ground next to him. The workers’ rights activist group Treta no Trampo has recently been fighting for those working in Brazil’s gig economy, targeting low pay, dangerous working conditions, and contracts that leave those injured at work on the breadline. The tech might now be more advanced, but the fact that worker exploitation is as old as industry was brought home to me by Eugênio Sigaud’s 1944 painting Acidente de trabalho [Work Accident]. Included in the group show “A máquina do mundo” [The machine of the world], this social-realist canvas depicts a man sprawled on the ground of a building site, his fate equally unknown, as colleagues look down from the precarious scaffolding and ropes far above.

Sigaud’s painting is among the oldest squeezed into this 120-year survey of art dealing with Brazilian industrial …

September 13, 2021 – Review

Conceição dos Bugres’s “The Nature of the World”

Oliver Basciano

Over a hundred pairs of inky-black eyes stare out of their glass vitrines. These are Conceição Freitas da Silva’s “bugres”: the diminutive figures that for over two decades until her death in 1984 the Brazilian artist carved from tree trunks and branches. The short smiles of some disarm, the longer grimaces of others give a more forlorn, or on occasion menacing, disposition. Their arms and legs are mostly demarcated by the slightest carved line, their heads flat-pated and running with the merest hint of neck into the stocky bodies. Their gender is indeterminate. Such was Conceição’s connection with the creatures that preoccupied her whole life—she made nothing else—she adopted the moniker Conceição dos [of] Bugres.

In the majority the bugres—a colonial-era racist slur for indigenous workers offensively perceived as “lazy buggers”—have a pale, yellowish, complexion that stems from the paraffin wax the artist used to decorate her carved figures. Most have a bob of straight painted black hair. Conceição had Kaingang heritage, an ethnicity native to southern Brazil: “I think that Indians have heads like that,” she said. “That’s the only way for it to come out.” Each of them possesses uniformity, to a point. Yet the longer you spend …

September 9, 2021 – Review

34th Bienal de São Paulo, “Though it’s dark, still I sing”

Felipe Molitor

In recent years, the common description of Brazil as a “polarized” country has shaped a national identity forged in resentment, which only fuels the fantasy that two equally radical factions are in dispute and that one must be annihilated. The 34th Bienal de São Paulo marks an attempt to avert this dystopia, guided by echoes from a distant or recent past. The result is an exhibition that is more reflective than activist, that sets out to listen rather than make claims. It seeks to bring about a meeting between ancestral and contemporary voices, creating a space for dialogue where each can be heard.

The show—curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, alongside Paulo Miyada, Ruth Estévez, Francesco Stocchi, and Carla Zaccagnini—opens with the Santa Luiza meteorite, discovered in Goiás in 1921. This survivor of the 2018 fire that gutted the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro (and other cosmic misfortunes) makes a strong opening statement about the ruinous state of the underfunded cultural sector in Brazil (echoed, through the exhibition architecture, by dominant shades of black that conjure an atmosphere of mourning). Contemplation of the object is interrupted by the tinkle and flash of metal pieces being transformed by a hired …

June 23, 2021 – Review

Maxwell Alexandre’s “Pardo é Papel”

Oliver Basciano

In early 2020 I attended a protest outside the police headquarters in downtown São Paulo. The small crowd had come to hear from the relatives of nine young people, all Black, who had been killed in a stampede when police fired rubber bullets indiscriminately across a packed baile, a dance party, in the south of the city. The authorities claim that these nights are a hotbed of gang activity and are rife with drugs. One young woman who spoke to the crowd, her voice flat, described how her 16-year-old brother, Dennys, worked six days a week to support the family and went to the party on his one day off. He never came home. This May, 27 residents of Jacarezinho, in Rio de Janeiro, died during a drug raid. Earlier this month, a young woman called Kathlen Romeu, who was pregnant, was fatally caught in the crossfire of a police shootout in the north of the city.

Both police violence and parties are subjects of the thirteen paintings by Maxwell Alexandre at Instituto Tomie Ohtake. In one work from “Pardo é Papel”—the series that dominates the exhibition and in which the artist depicts his scenes of favela life using acrylic, …

December 16, 2020 – Review

Jonathas de Andrade’s “Achados e perdidos”

Oliver Basciano

I’ve been on the search for a new swimming pool in São Paulo since my regular haunt, Estádio do Pacaembu, was first closed to house a Covid-19 field hospital on the adjoining football pitch. And while cases have eased, the pool remains drained and shuttered as it undergoes refurbishment. The plans for Pacaembu, which includes an E-Sports center, hospitality areas, and the new Brazilian outpost for the Italian gallery Continua, are a far cry from the musty changing rooms and faded concrete terraces of its previous incarnation. But the old Pacaembu was free and attracted a wide range of Paulistanos, an oasis in a city of concrete, traffic, and noise. The alternative public pools I searched out are in near-dereliction or closed; the private club a well-meaning friend (clearly unfamiliar with the economics of art writing) recommended was off-putting not just in price but in its website’s reminder that members’ nannies were not eligible to swim. The swimming pool is a microcosm for Brazilian society, its class and racial fractures reflected in the chlorinated water.

For the past ten years the Brazilian artist Jonathas de Andrade has been collecting swimming trunks he finds discarded or forgotten in the changing rooms …

November 3, 2016 – Review

“Homo Ludens”

Daniela Castro

The first sentences of Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (1944) read: “A happier age than ours once made bold to call our species by the name of Homo Sapiens. In the course of time we have come to realize that we are not so reasonable after all.” Actually, the sentence goes on but I cheated and decided to end here for dramatic purposes. Cheating is the doppelgänger of fair play anyway. For instance: in Brazil, a president democratically elected with 54 percent of the popular vote, who doesn’t face any criminal charges, gets impeached by the Congress and the Senate, two thirds of whose members do. In the municipal elections of São Paulo, a highly botoxed but completely unknown face in the political sphere, aligned with the former center-right, now super-conservative Social Democrat Party, wins over 53 percent of votes in the largest city in Latin America. The rules of the game are distorted while the game is still in course: politics get in the way of politicians, democracy gets in the way of liberal capitalism.

At this unstable time, when culture and all its players are marked by uncertainties, Ricardo Sardenberg curates “Homo Ludens” …

September 15, 2016 – Review

“Live Uncertainty,” 32nd Bienal de São Paulo

Kiki Mazzucchelli

Almost a year ago, when chief curator Jochen Volz announced his proposal for the 32nd edition of the Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil was already undergoing a severe political crisis, with the country split between those who supported the democratically elected coalition government and those who called for the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff. Titled “Incerteza Viva” [Live Uncertainty], the exhibition opened to the public only a few days after Rousseff was permanently ousted from office in a controversial trial based on corruption charges that paradoxically ensured that political sectors known to be corrupt remain in power. In his inauguration speech, unelected president Michel Temer stated that uncertainty had finally ended, but the demonstrations that have been taking place almost daily across the country since Rousseff’s impeachment seem to point to the contrary. During the biennial’s preview, a group of artists wearing black t-shirts with slogans from the late dictatorship days— such as Eu quero votar pra presidente [I want to vote for president] from the Diretas Já [Elections Now] campaign, and the more up-to-date Fora Temer [Out Temer]—took to the Oscar Niemeyer pavilion that hosts the exhibition. Apart from a few scuffles with members of the public, the protest …

April 10, 2015 – Review

SP-Arte

Silas Martí

There is a clear spatial hierarchy at art fairs: modern and old master works on one side, contemporary on another. But this year’s SP-Arte, in its 11th iteration, inaugurated a new section called “Open Plan,” installing the most ambitious and large-scale works on the third floor of Oscar Niemeyer’s Bienal pavilion, a space usually left empty. High above, hanging over the curvy ramps of the modernist building, is a makeshift bridge, a fragile structure of wood and strings built by artist Rochelle Costi (Residência – escada, 2010/15, presented by Luciana Brito, São Paulo; Celma Albuquerque, Belo Horizonte; and Anita Schwartz, Rio de Janeiro), that casts a shadow over the main exhibition hall below.

The dangling footpath that sways and rocks to the buzzing crowd all around stands as an informal line of demarcation, dividing the pristine upper floor, where works stand free of constraints, and the packed fury of sales at booths and stands throughout the rest of the pavilion. In all its uselessness, it’s a symbol of fairs’ deepening crises of identity as they increasingly want to resemble institutional exhibitions. When it comes to this particular building in Ibirapuera Park, the crisis is even more resonant. Home to both the …

September 10, 2014 – Review

São Paulo Round Up

Sophie Goltz

The past 10 years have seen an expansion in the recognition of Latin American artists worldwide, as well as a multiplication of the numbers of galleries and art-related events in Brazil, especially in São Paulo. Being so, a survey of the city’s growing number of contemporary art institutions such as galleries, museums, studios, and off-spaces can only be partly representative of the city’s vast landscape of art and culture. But a survey can nonetheless offer another view on the cultural life of Sao Paulo beyond the world’s second oldest biennial (after Venice, and founded in 1951), which has just opened it’s door to the public. While the Bienal is looking for the very contemporary in art today and doesn’t necessarily meet local expectations for its representation of Brazilian art, the city’s current gallery exhibitions present a consolidation of a Brazilian identity through art and its spaces.

At CAIXA Cultural, in the rather dilapidated downtown of São Paulo, French artist Marie Voignier’s film Hinterland (2009) examines Tropical Island, the man-made bathing resort in Krausnick, a bleak and economically depressed region 60 km south of Berlin. Set in a heated dome that looks like a real-life Truman Show, the film deals with the …

September 5, 2014 – Review

“How to Talk About Things that Don’t Exist”

Silas Martí

When British curator Charles Esche moved to São Paulo to orchestrate this year’s Bienal—alongside Galit Eilat and Oren Sagiv (from Israel) and Pablo Lafuente and Nuria Enguita Mayo (from Spain)—he stressed that this is a show anchored on the now, on the goings-on that are shaping the world as we know it today. It just so happens that this very world has undergone seismic shifts since Esche and his team set foot in São Paulo, from the protests that shook the city and the rest of Brazil last year and became known as “the June uprisings” to the tumultuous World Cup and the upcoming elections with a campaign now on full throttle and jarred by the death of a candidate in a plane crash. Meanwhile, Israelis and Palestinians continue to fight on the Gaza strip, with a death toll up in the thousands. This latest episode fueled a protest that took the biennial by storm days before its inauguration. Artists launched a manifesto rejecting financial support from Israel, which afforded the country a logo among the biennial’s sponsors. While the curators titled the show “How to Talk About Things that Don’t Exist,” it appears that the things that do exist …

April 29, 2014 – Review

Marine Hugonnier’s “The Bee, the Parrot and the Jaguar”

Filipa Ramos

Eighteen years have passed since Hal Foster’s critical remarks on the position of the artist as ethnographer. That text, together with Catherine David’s 1997 Documenta X, and its questioning of the anthropological foundations of Western culture, became two groundbreaking events, which heralded a tightening of the artistic and anthropological inquiries that have emerged up to the present day.

If the early 2000s witnessed a period of relative downturn in interest for the methods, topics, and scenarios of ethnographic observations and anthropological comparative analysis, we are currently experiencing another ethnographic revival in artistic practices, which—just as in the mid-to-late 1990s—has been simultaneously evidenced and stimulated in exhibitions by both theoretical ventures like Anselm Franke’s “Animism” (2010–12), and major perennial platforms like Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s Documenta 13 in 2012.

Marine Hugonnier is a London-based artist who has been carrying out a long-standing exploration of the crossroads between anthropology and philosophy. “The Bee, the Parrot, the Jaguar,” her solo show at Galeria Fortes Vilaça, presents an important moment in her inquiry, which engages with the writings of Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, a key figure for current trajectories in philosophical realism and the critical evaluation of modernity’s culture/nature dualisms.

All sorts of potential life forms created …

January 27, 2014 – Review

"Secret Codes"

Fernanda Lopes

“If it does not work, I will close it next month,” Luisa Strina decided when she first opened her gallery in São Paulo in 1974. She wanted to be an artist, but soon realized she was more interested in the universe surrounding the work of art; the artists Luiz Paulo Baravelli, Carlos Fajardo, and Wesley Duke Lee, who taught at Escola Brasil, an experimental art school she attended in São Paulo, encouraged her to open a gallery. At that time, Brazil had very few commercial art spaces, Latin America was less integrated than it is now, and the Brazilian art market was virtually nonexistent. As it turned out, the “next month” never arrived and four decades later, Galeria Luisa Strina remains one of the most important contemporary art galleries in Brazil.

To celebrate its history, the gallery inaugurated the exhibition “Secret Codes” this past December. Organized by the Spanish curator Agustín Pérez Rubio, this group show is an overview of the history of Conceptual art, bringing together thirty-two artists from Brazil and abroad (only five of which are represented by the gallery) and almost forty different artworks dating from the 1960s to the present. This well-conceived exhibition pays tribute to the …

September 28, 2012 – Review

"The Imminence of Poetics" 30th São Paulo Biennial

Sophie Goltz

“Welcome to my life” is written in large letters on a wooden board, announcing the uphill spill of an urban landscape made of brightly painted hollow bricks. Meanwhile, further multilingual signs—many not without humor—ask so-called favela tourists for donations. It’s been at least since the year 2007 that the Project Morrinho was made known to the international art audience, when this initiative of young people from a favela district in Rio de Janeiro was invited to participate in the 52rd Venice Biennale. Having begun as a survival strategy of children, and having changed the reality of life in this community, today it is a recognized “Favela Art Project,” which enables inhabitants to narrate their own living conditions amidst a prosperous society , beyond violence and poverty and from the perspective of the production of desires. That is to say, desires do not only exist in one’s imagination; rather they create realities on their own terms, which can change the lives of all involved.

But what does this project have to do with the 30th São Paulo Biennial? With “The Imminence of Poetics” being the main leitmotif, this year’s artistic director Luis Pérez-Oramas and his curators Tobi Maier, André Severo, and Isabella …

October 5, 2010 – Review

Politics and "The Political" at the 29th São Paulo Biennial

Octavio Zaya

How do you follow, and what do you do after “The Void,” the so-dubbed 28th edition of the São Paulo Biennial (2008)? Its Artistic Director, the internationally known and experienced curator Ivo Mesquita, left the huge second floor of the Oscar Niemeyer building entirely empty as a comment on the intricate bureaucratic politics of the event, and on biennials in general. His budget had been reduced as well, from the $12 million of the previous 27th Biennial to a mere $3.5 million, and he left a debt of some $2 million. He selected just over 40 artists to convey a radical curatorial statement, while trying to place the 28th Biennial “in living contact” with the art of the world.

In contrast, this year’s 29th edition, said to be anchored by the notion that “it is impossible to separate art from politics,” has benefited from major advantages: the commitment and resolve of the new president of the Foundation (elected last year), the well-respected consulting executive Heitor Martins, who presided over a spectacular turn in the finances of the SP Biennial; as well as a new Biennial Council, directly linked with the arts. On top of all that, this edition had at its …

Load more