That only 6 of the 75 locations numbered on Glasgow International’s essential city map are host to the “Director’s Programme” says something of the generous weave of the “official” and the “collateral” here, doing away with the two-tiered hierarchies usual in such events. Instead, a loose net is cast around existing public institutions, non-profit spaces in studio complexes, artist-run galleries, and commercial venues, with the odd special location thrown in. Though touted by the City Council as proof of Glasgow’s status as a “global leader in contemporary art,” director Sarah McCrory states that G.I.’s aim is rather to “highlight and support the activity that takes place throughout the year,” and to “focus on the important Glasgow-based artistic community.”

The center of gravity for this artistic community remains the Glasgow School of Art, so it was fitting that Thursday night’s opening party was held there, in the dark upstairs bar commandeered for the night by Marvin Gaye Chetwynd and the performance troupe MEGA HAMMER. Their endlessly morphing performance at times took to the stage but was more often ensconced amongst the audience members. A leotarded woman lying prostrate on her back gently prodded viewers with her two-meter-long pink prosthetic leg; cross-dressed waiters enticed the crowd with trays of miniature ice-cream cones filled with a mousse of trout, kale, and chocolate; a face-painted woman bawled into a microphone, attended by a six-legged spider-like configuration of costumed bodies. Meanwhile Chetwynd herself, naked except for a shrugged-off gold lamé coat, head-to-toe red body paint, and a pair of sagging papier mâché dugs, seemed enraptured by the efforts of her fellow performers. As the performance came to an end and segued into an energetic dance party, the floor slick with spilt beer, I wondered if this is really what a global leader in contemporary art looks like?

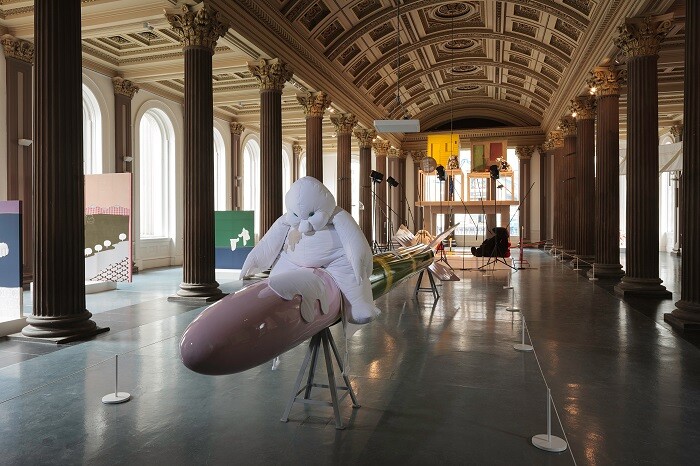

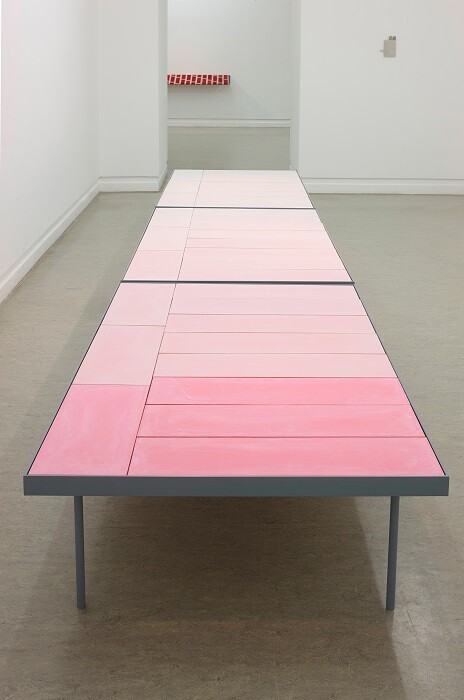

The improvisation and am-dram aesthetics of Chetwynd’s work set the tone for many of the offerings of McCrory’s core Director’s Programme: highly detailed, craft-oriented work that tended to follow its own material logic. Tamara Henderson’s theatrical mise en scène in the ornamental hall of the Mitchell Library presented a field of characters in elaborate hand-sewn costumes around a monstrous central figure named Garden Photographer Scarecrow (2016), whose camera-arm photographed the installation each day. An undisclosed narrative seemed to feed this dense and personal exhibition, made on residency in the coastal town of Arbroath. At the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), “Who’s Exploiting Who In The Deep Sea” by Cosima van Bonin brought together a collection of works from 2006 onwards adopting a seaside theme: stuffed, furry octopi, lobsters, and seashells open to reveal peeping cartoon eyes. Upstairs, Glasgow-based Tessa Lynch’s exhibition “Painter’s Table” was a delicate collation of more introverted work extrapolated from observations made on her daily commute from home to studio. On the other side of town, in the semi-derelict spaces of the soon-to-be-revamped Kelvin Hall, a room full of double-sided, unstretched paintings by Helen Johnson (such as Social System, 2016) hung from the ceiling like banners, their richly worked surfaces approximating tapestry. Up a shabby, paint-peeling staircase, the upper hall hosted Bright Bodies (2016) by Glasgow-based Claire Barclay, a sculptural arrangement with swathes of red rubber and raw steel cages responding to the shifting history of this municipal venue.

The only group show of the Director’s Programme turned its focus more directly onto Glasgow’s industrial legacy, its history of shipbuilding and textile production, fittingly installed in the industrial spaces of Tramway, a former tram factory and depot where the old tracks remain embedded in its floor. The five artists brought together here showed work that linked thematically but jarred aesthetically, despite the engagement of a sixth, Glasgow native Martin Boyce, invited by McCrory to design the exhibition layout. The corrugated metal and plastic screens he introduced to act as frames between the works ended up adding yet another incongruous element. Nevertheless, Sheila Hicks’s Mighty Matilde and her Consort (2016) commanded the room with a tumbling cascade of colored yarn which seemed to treat fiber in space like pigment on canvas, nodding to the delicate woven elements spanned across Alexandra Bircken’s metal “trolleys” (2016) riding the tracks on the floor.

Mika Rottenberg’s films, which give the anonymous trappings of office culture and cottage industry a surreally squelchy feeling, are always uncomfortable viewing, but Squeeze (2010) and NoNoseKnows (2015) made sense here within the framework of industrial legacies. Lawrence Lek’s computer-generated animation about the legacy of the QE2 (QE3, 2016) could not be further removed stylistically, but tapped into local histories distant and recent in time, and proposed the repurposing of the retired liner to house the Glasgow School of Art, whose famous Charles Rennie Mackintosh interior was gutted by fire in 2014. Shown separately in a vast, darkened room, Amie Siegel’s stately film Provenance (2013) traced in reverse the journey of high-priced pieces of modernist furniture from auction room back to their humble beginnings in Chandigarh, revealing the elaborate trappings of an industry devised to construct and maintain value. She presented this literally back-to-back with another film, Lot 248 (2013), which documents the auction at Christie’s of her own film. This tautological maneuver describes the same mechanisms at work in the art world, an industry in which any art producer is implicated to some degree, as this neatly tied-up work implies.

Beyond the Director’s Programme, the common denominator was difference, and each person I spoke to during the opening days had their own list of highlights, from Louis Michel Eilshemius’s early twentieth-century pastoral fantasies at the artist-run 42 Carlton Place, to Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari’s poignant meditations on love and desire in drawings, photographs, and film at Common Guild, another non-profit gallery located in an artist’s home (this time Douglas Gordon’s). Glasgow Sculpture Studios’ two-person exhibition “You be Frank, and I’ll be Earnest”—pairing New Yorker Alisa Baremboym’s perforated steel, acrylic, and shrink wrap sculptures with Canadian Liz Magor’s combinations of cast cardboard and salvaged oddments in Ziploc bags—proved propitious, while high up on the list for many were the imagined portraits of bearded black men (such as Self Examination, 2015) by Derrick Alexis Coard, curated by Matthew Higgs at Project Ability. Impressive too was Monika Sosnowska’s baroque concoction of twisted steel (Façade, 2013) at the Modern Institute, and Sol Calero’s hacienda-inspired set for a telenovela filmed in situ at David Dale Gallery (Desde el Jardín, 2016).

With its heterogeneous conglomeration of shows made by diverse artists in diverse venues, each with a different remit, Glasgow International’s lack of singular focus allows for a rare realism. Resisting the kind of rapid and narrowing consensus-building that comes to dominate such events, instead it offers proof of another kind of industry: the small-scale labor of the individual artist, working separately or as part of a loosely knit community, making their own work or staging exhibitions for others. McCrory’s emphasis on craft and other practices that operate beyond the art market posits this kind of individualized industry as a continuum of Glasgow’s traditions, and as a vibrant center for cultural production.